Debbie Hewitt Smith, Leland Academy, Class of 1974 Leland, Mississippi

“How many of you are planning to go to the new academy?” It was 1969. I was in the eighth grade, and this was the last P.E. class at Leland Junior High before Christmas break. All the eighth-grade girls, including a small number of African-American students, were sitting on the bleachers waiting for the bell to ring when our white instructor yelled out the question. I hesitantly raised my hand. On the inside, I was wondering why on earth she would ask such a question, especially in an integrated class! I was too embarrassed to look at the black girls to see what their reactions were, particularly when Miss Signa acknowledged our response with a hearty “Great! Good for you!” The “academy” she referred to was the fledgling Leland Academy, one of many segregation schools springing up in the Mississippi Delta at that time.

Leland Academy was rather late to the game, thanks to years of stall tactics. In 1966 white leaders in Leland made attempts to satisfy the majority-black population with a plan called “Freedom of Choice.” I was in fourth grade that spring when I was handed a form at school asking me to check where I wanted to attend school next fall, the choices being Lincoln School and Dean Attendance Center. My teacher went around and quickly pointed out to us we should check the latter, which was the official name of our then all-white public school. I say “then” because the following September a handful of very nervous-looking African-American students made the choice to leave “their” school to come to “our” school.

That first day of racial integration in September 1966 passed with little incident other than several white students rushing over to watch some of the first black students disembark from the school buses. No racial epithets were shouted nor any rocks thrown, but I’m sure those poor students, gazes fixed firmly on the pavement, could feel the eyes of all those white students icily staring at them like they were part of some freak show.

Nothing much changed over the next three years. Every spring we all dutifully filled out the Freedom of Choice form. Each year there would a few more black students who braved making the switch from their old school. I don’t recall any racial problems. White students kept to themselves, and black students did the same. There were subtle microtensions, usually between black students and white teachers, such as my seventh grade history teacher relentlessly correcting a black girl’s pronunciation as she read aloud from our textbook in class. But there were no fights that I recall. I naively thought all was well.

But then in the summer of 1969, African-American leaders in Leland and the federal government pressed for more systemic integration than the Freedom of Choice approach. I remember my parents’ fixation on the pending court decision that summer. Undoubtedly white leaders were doing everything they could to stonewall the inevitable. I knew things had come to a head the day my best friend and I were out walking, and I was surprised to see my mom’s gray Impala headed towards us. She stopped and rolled down the window to tell me she was headed to Indianola (about 15 miles away) to put in my application at the academy there.

It must have been quite a crowd at Indianola Academy that day because I ended up on a long waiting list. That prompted a sudden interview for me at St. Joseph Catholic School in nearby Greenville, which, prior to the 1960s, was THE only private school I was aware of in the Delta. That was when I realized how panicked my parents were. In my mother’s eyes, Catholicism was one step above practicing voodoo, so I was shocked when she and my dad plunked down a deposit for me to move to St. Joe.

I was granted a reprieve from the good sisters because no court changes came down by the start of school in fall 1969. I was back in public school but with fewer of my friends. Many had moved on to academies already.

Actually, it was a great semester for me. I was infinitely happier with my classes and my teachers. Best of all, I finally persuaded my mom to let me join the marching band, something I had nagged her about for years. Our band director, Mr. Cadden, started me on clarinet lessons when school started. Then, once I could play a C major scale without squawking, he whisked me through the music tests I had to pass in order to rehearse with the full band. I was overjoyed to have that privilege for all of one week at the end of the semester. Then my parents let me know I would be leaving the school I had known since first grade. The federal courts’ October order for system-wide integration was to start January.

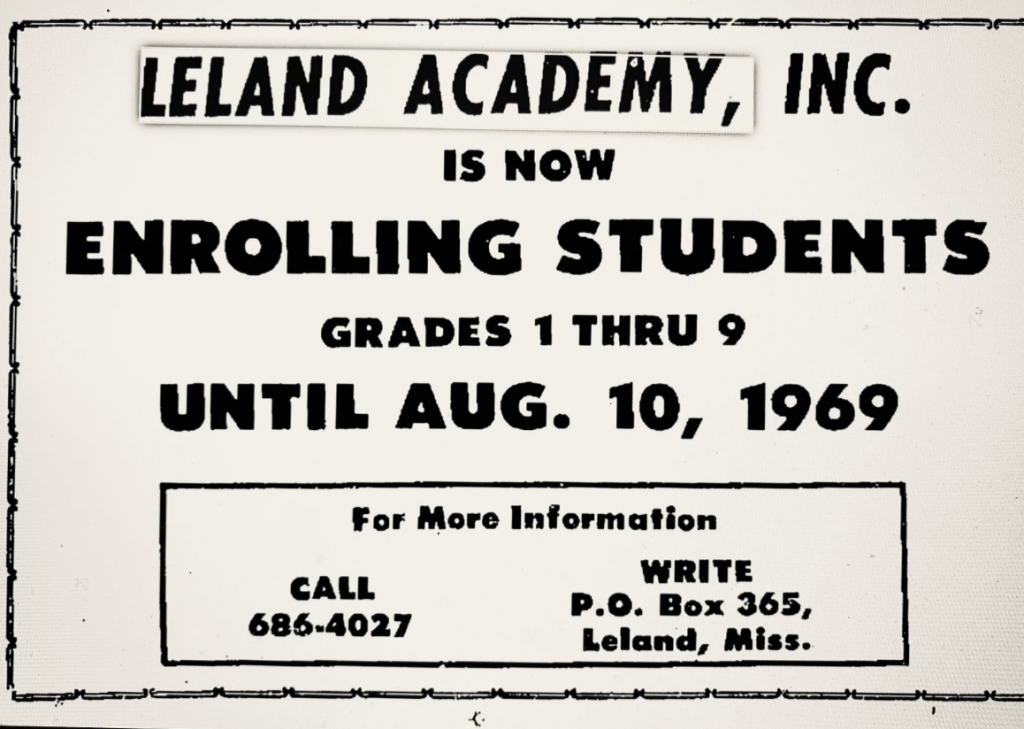

So my school days at Leland Academy began. LA had been hastily thrown together the previous fall but initially offered grades one through six only. Its “buildings” were the borrowed Knights of Columbus hut and American Legion hut. After the court order, the academy added seventh and eighth grades. My eighth grade class met in the Boy Scout hut, an old wooden lodge otherwise used for troop meetings. We had three rooms available for the seventh and eighth grades: two small rooms connected by a large common space with a fireplace. That fireplace and the many marshmallow roasts we were allowed were the only happy memories of that semester. What had started out to be one of the best years I ever had in Leland public schools was derailed. I felt like I’d been thrown in the ditch

We only dealt with temporary housing for one year. By the start of school in the fall of 1970, Leland Academy’s new cinder block building seemed to pop up overnight in a cotton field. Not only were we now first through twelfth grade, but we were also home to a football field, track, gymnasium, and baseball field. By God, there was to be no interruption of sports! However, gone were the public school award-winning marching band, my rookie claim to being a clarinetist, chorus and everything else that had ever lit up a music nerd like me. All to defy the idea of an equal school system.

I was never given an option to go anywhere else for school, so I rebelled in the only way an obedient child like me could: I withdrew into numbness my entire freshman year at the academy. I quit all my outside activities except piano lessons. Yet even piano was not the same—also due to racism, in fact. The teacher I had studied with since I started lessons at age six moved away. The reason? She and her family had been unmercifully harassed the year before when her youngest daughter started appearing publicly with her black boyfriend. I remember going to a lesson at her house, one of the beautiful older homes that lined scenic Deer Creek, and seeing the words “n— lover” bleached into the green grass blades of her pristine front yard. I was shocked, saddened, and very confused at seeing something I never imagined happening in my town and to someone who was so very quiet and unassuming. I quietly imploded, drifting through the ninth grade, hating everybody and everything.

Surprisingly enough, even those students who had everything they dearly loved still at their disposal (i.e., sports) didn’t seem thrilled to be at this new school either. While our parents were always on the frontlines cheering us on (after all, they were paying a lot of money, which strapped many, for the privilege of an all-white school), there seemed to be a pall over the student body that first year. Pep rallies were positively depressing compared to what they had been at Leland High. There was no pep band, no victory torch, no tradition.

In fact, when it came to creating traditions at Leland Academy, we basically stole them from our old public school. For the new school mascot, the student body came up with the Bruins, only a baby step away from the public school’s Cubs. Our fight song was the same one used at Leland High, just substituting the old school colors of maroon and white with new colors red and blue. We even continued the long-held Leland High tradition of the juniors making and presenting a magnolia chain at graduation, which included a maudlin song about the magnolias being a symbol of “love in our hearts.”

Things settled into a drab routine. I can’t say it got better over the years. I didn’t get a great education, but it wasn’t exactly a poor one either, in terms of basic high school classwork. We gradually added a few clubs and landed a Beta Club chapter, but there was never a choir or band or theater group, not even music or art classes for the lower grades. At the academy we swapped the arts for the trade-off of a whites-only school, a barebones one. Sports had always been an important part of life in a small town (after all, this was the South!), but at least in the public school there was an attempt at well-rounded offerings.

At our graduation ceremony in 1974, I recall my classmates weeping because we were going our separate ways. All I remember feeling was a sense of not being able to separate fast enough.

I’d like to say that my eyes were fully opened to the ingrained racism of Mississippi once I left Leland to go to college. They started fluttering once I was a Mississippi College music major (I made a few black friends, unbeknownst to my parents), but it was not until I was working on a master’s at the University of Memphis in the early Eighties that my watershed moment came. My Michigan born-and-bred organ professor at UM was invited to play a recital at a church near Leland. The week after his recital, I asked him what he thought of the Delta. He looked me square in the eye and replied with much pain in his voice, “I could NOT believe the poverty.” I was stunned. My immediate thoughts were, “What are you talking about? What poverty?” And then those thoughts in turn brought up the disturbing question, “How could I have not seen something in twenty-five years that was immediately obvious to my teacher in three days?”

From that day on, every time I visited my parents in Leland I forced myself to really look at what had been right in front of my eyes my entire life and see through the camouflage. Instead of the acres of snowy cotton that the Delta is famous for, I focused more on the tiny derelict shacks in the middle of all that wealth, realizing that entire families lived within those ramshackle four walls, often with no electricity. I paid attention to my parents’ language and those around them when they talked about whites versus the way they spoke about blacks.

Or didn’t speak, such as when my daughter was showing my mom some photos taken of her with her friends at school, and how my mother gushed “cute” or “pretty” when the friends were white, but said nothing when the friend was Indian or Pakistani or (gasp!) black. That subtlety brought home the realization that the “N” word didn’t have to be flaunted to plant seeds of racism – silence at the right moment works just as well. And over the years, I listened to my parents lament the sorry state into which the Leland public schools had fallen, and I grieved over their blindness to their role in that process.

My father died in 1999, and my mother moved from Leland to a Dallas retirement community. My children, who only remembered the idyllic times they spent with their “mamaw and papaw,” were devastated the day we helped my mother move. I felt a few pangs, but I was more relieved that I no longer had a reason to have to come back to a place that was still divided between “Us” (white people) and “Them” (black people).

Over the next 20 years, I witnessed how time was not kind to the Delta, an area that stubbornly refused to give up its racist ways. Leland Academy closed many years ago. I wish I could say that many of the other segregation schools have also disappeared, but that’s untrue. White students from Leland typically now go to the private schools in larger nearby Greenville.

The town of Leland itself struggles now. One of its few current tourist attractions is the Jim Henson museum, honoring The Muppets creator, born and reared there. In fact, my older sister had also been friends with Henson’s childhood friend Kermit Scott. Henson eventually named Kermit the Frog in his old Leland schoolmate’s honor.

Ironically, in 1969, the same year that Leland white parents were fleeing public schools and flocking to Leland Academy, the town’s most famous son was busy launching Sesame Street in New York, the game changer in children’s television. The lasting aim of Sesame Street, Big Bird, Kermit and the rest of Henson’s puppets was to educate and nurture all U.S. children, but particularly those who were black and brown. It seemed that in 1969, U.S. society was giving black children the message that their lives weren’t as valued as white ones, nor did their prospects of learning matter enough to society at large. As a Leland Academy alum, I don’t have to look far to know how true that was.

Debbie Smith teaches music at Rhodes College in Memphis and has been active as a teacher, recitalist, accompanist, singer, and choral director in the Midsouth. She is also Assistant Organist-Choir Master at Grace-St. Luke’s Episcopal Church in Memphis.