You learn along with your students if you’re a successful teacher. In over 36 years as a band director, I’ve had a solid education in young people and their communities. I’ve become a part of young people’s lives from fifth grade through high school in schools in Mississippi and Tennessee. When students have walked through my door, they’ve brought things with them, such as hopes and dreams, and sometimes, baggage, fears, and things they’d rather not discuss.

They’ve taught me as much as I’ve learned. That includes my time teaching at a white academy, a two-year experience sandwiched between my career with public school bands.

My first job had been at Eupora High School, in Webster County, followed by returning to the University of Mississippi for a master’s of music and a graduate assistantship with the Pride of the South Band. With my master’s, I headed to Humboldt (Tennessee) High School but was ready to get back to Mississippi by 1989.

The only Mississippi band openings I found that year, however, were at several white academies. That’s where I landed. I became band director at Starkville Academy, a private school founded two decades before as a white escape from public school integration. I didn’t think too much about the academy’s political messaging, to be honest. I was just glad to finally get a band job back in Mississippi, elephant in the room or not. Even in the post-integration Eighties and Nineties, Starkville Academy continued to be the target of NAACP lawsuits for allegedly receiving public support for free water and electricity and state tuition grants for disabled students.

All my band students at Starkville Academy were white—with the exception of one Asian middle schooler. His non-white skin drew such attention at a football game at Greenville Christian School that when the young man walked to the concession stand, one man said loudly, “I told you I saw a Black young ‘un in a band uniform!”

In my pre-academy five years of teaching, I’d always had diversity among my students. Everyone else on the Starkville Academy campus was white except for two African American custodians, a husband-wife team simply called Johnny and Betty. They never publically showed if the atmosphere bothered them. I got the impression that they were happy to have gainful employment. They were a good-hearted couple who would do most anything for those around them.

I don’t mean to say that the band students at Starkville Academy weren’t great kids. They were all so similar, however. The only difference was their specific spot on the middle-class spectrum. Some families were white-collar professionals, while other families were clearly struggling to pay the tuition to keep their children in the school. Many hoped to eventually attend nearby Mississippi State University—numerous Starkville Academy parents worked at the state university. Their school was white, their churches white. Their view of the world was insulated.

I’d received a friendly piece of advice from another music teacher in Starkville about my new academy students: they could be pushed to excel, but if you really tried to tighten the screws and push them harder, they would shut down on you. These were students used to some coddling and deference. My job interview hadn’t just been with the academy headmaster, but also with a committee of band parents. Once I scheduled an evening rehearsal in preparation for the Mississippi Private School Association State Concert Festival. I was aggravated when six or eight students missed the rehearsal. The excuses I received from parents were things such as “my child is really stressed right now and needs some down time” and “my kid needs to study for a test” when they knew weeks before the schedule of extra rehearsals. Another time a parent stepped in over our band playing the 1958 Latin-beat rock song Tequila. It wasn’t that she exactly disliked our instrumental version. She didn’t like that some students would shout “Tequila” on cue. She felt free to offer her input.

I left Starkville Academy after two years and returned to public schools, moving to the Jackson area. I taught at Northwest Rankin, Crystal Springs, and Florence and had far less parent micromanagement to deal with. I smiled to myself when I watched my students at Northwest Rankin grooving to a drum beat they called “The Butt Dance.” It’s hard to imagine my old academy parents dancing and singing “Let’s Do the Time Warp Again,” as did Northwest Rankin parents when our band opened their marching show with The Rocky Horror Picture Show number.

I’ve taught students from all walks of life in central Mississippi, in contrast to those white academy years. I’ve had Protestant, Catholic, Jewish and Hindu young people. I’m sure I’ve had agnostics too. Programming a Hanukkah song on a holiday band concert becomes the norm when you have Jewish families in your band program. Other holiday selections have to be chosen carefully. No one assumes every student is from the same kind of family background. That’s never a public school possibility.

I’m in Forest, Mississippi city schools now, having taught in the outlying Scott County schools before that. I’ve been in the Forest/Scott County community for a total of almost fifteen years. At Forest, my band program is made up of African-American, Hispanic, Asian, and a few white students. It is a cross-section of the local population. I’ve seen the best interaction between black and white students here.

All this is not to say there’s no academy in the Forest area either. I know that some of the Forest faculty send their own children to East Rankin Academy in Pelahatchie, twenty miles away. I think about how academies and charter schools draw off money and resources from public schools that are already struggling. I think in those terms when I listen—I can’t stomach it too long—to SuperTalk Radio network in the car. The Mississippi politicians invited on the radio talk shows take such an anti-public school stance. Their comments aren’t outwardly racist, but seem so condescending of public schools. I wish they experienced my students. I look in the faces of my kids, and I can’t imagine any teacher not loving them.

Here’s something I’ve noticed about my students in Forest: these kids unthinkingly share. I teach general music classes in the high school and the middle school. Frequently, a student shows up with a bag of snacks—hot Cheetos are big now—and proceeds to share with everyone in class. It touches me to see how automatic that simple regular gesture of common ground is. They don’t have a hoarding “This is mine, not yours” mindset. That goes for food brought from home, too. Hispanic and Asian students make a point of proudly bringing, say, homemade tortillas or candy from a summer visit made to China to underscore their family’s particular background.

After bringing my Forest High School Band roster home one afternoon, my North Carolina sister-in-law gazed over it and replied “Now this is America!” It really is a combination of races and cultures. The learning environment is great. Currently, the students that I teach are some of the most well-rounded individuals you’ll ever encounter in today’s world. I’m grateful to get to be learning from them and our community together. You could say I’m now in advanced placement.

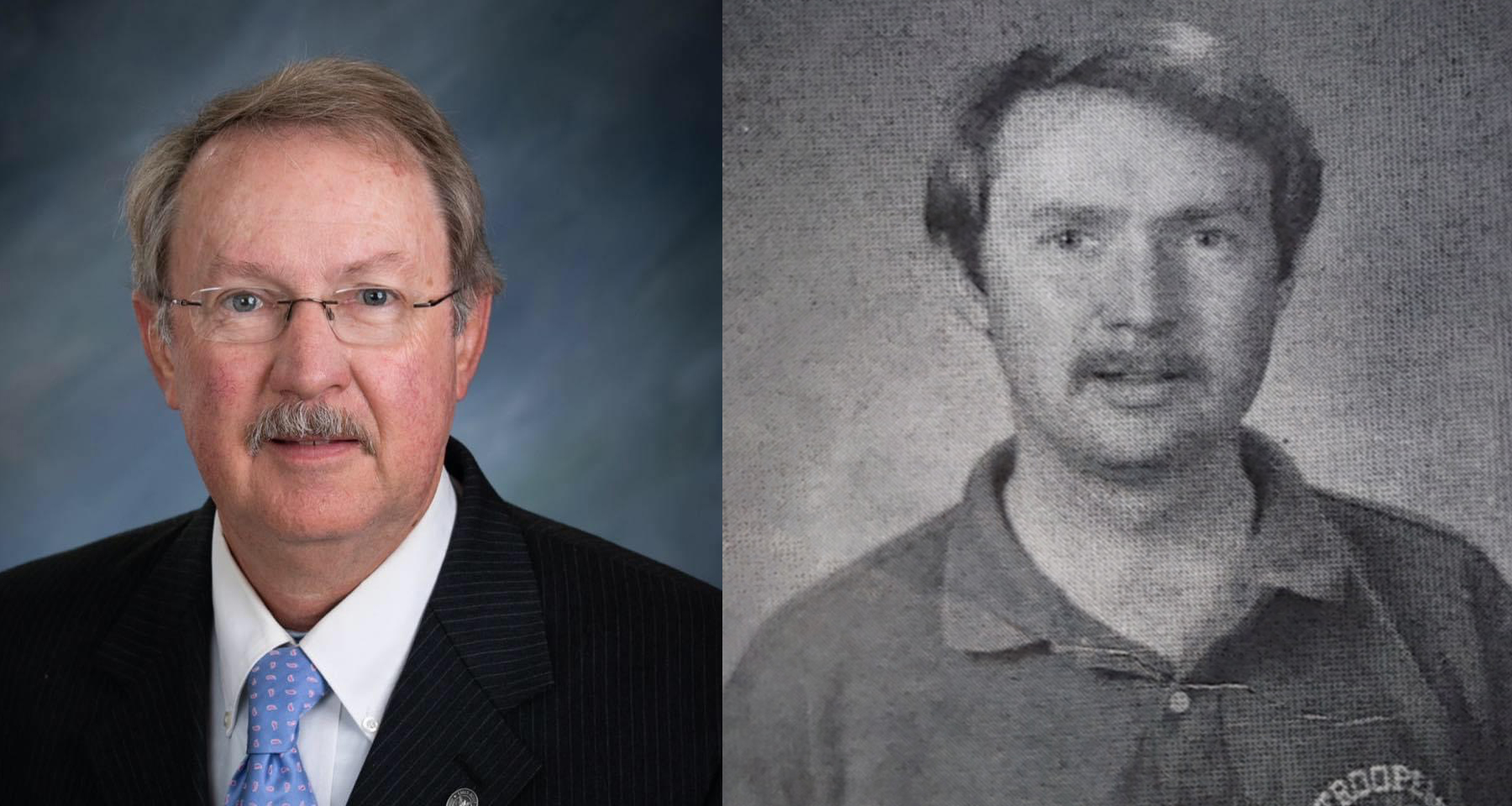

Mark S. Davis is Director of Bands in the Forest, Mississippi Municipal School District, where he enjoys sharing the gift of music with young people. He’s a native of Bruce, Mississippi. He lives in Pearl with his wife Lisa Behrendt Davis, a French horn player in the Mississippi Symphony Orchestra.

Every school district has its own story. In some kids made an effort to get along. In others, whites found themselves the victims of anti-white violence and harassment. Of course these students would leave a school district where they were not wanted.

Mark describes hearing a racist comment at a Greenville Christian School football game in 1991. Today this school is majority black. Times change. People change. An inquiring mind might ask about how if going to private school is so much about racism, why are so many black students now choosing private schools?

I am not a teacher by trade but am teaching at a private school this year to allow the small class sizes needed for COVID restrictions. I’ve found that my students tend to share their cookies and potato chips, too.

This is well written and well stated. You have touched the lives of the young people you’ve taught. Your students lives are richer because they are exposed to different cultures and religions… and they are also enriched because they have a kind, understanding, and welcoming band director. Well done, Mr. Davis, well done!

This is very enlightening. Thank you, Mark Davis, for such an eye-opening insight into band directing and the issues involved. Band directors, in general, are much under appreciated for the positive influences they have in student education and development.

Mark Davis’ narrative is true to the experiences I had as a student in the late 1960’s and early 70’s, and that I saw repeatedly as a 31-year public school teacher myself. I find it both revealing and pathetic that the movement to have public money go to private schools has gained such momentum among so many of those who fled the public schools. As they fled, they paid tuition to engage in their white flight, yet now they feel entitled to public funds to pay that same private school tuition. From my years of teaching, almost entirely in schools with student populations similar to those that Mark serves, I too would not have exchanged the students with whom I worked for any private school situation. Your students are no doubt grateful for you not having abandoned them and for believing in a public education for ALL students – congratulations, Mr. Davis!