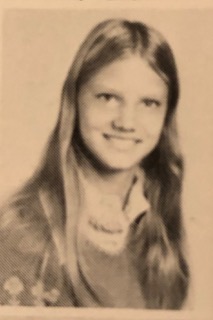

Ellen Morris Prewitt-Myers Park High School-Class of 1975-Charlotte, North Carolina

In the fall of 1969 when the United States Supreme Court thundered its Alexander v. Holmes “Now, dammit!” ruling that ordered white Southerners to finally integrate their public schools, I was watching my mother get married. Mother, ten years a widow, wed Mr. Van Hecke in the living room of our Jackson, Mississippi, home. The jewel buttons on her blue silk suit sparkled. We didn’t know it at the time, but Mother’s remarriage would send us to North Carolina and slap into the inauguration of court-ordered busing in America.

I was halfway through my first year at Bailey Junior High in Jackson, a city saturated with rumors of coming integration. The “freedom of choice” integration we’d had at Power Elementary, where one or two Black kids were allowed into otherwise white classes, hadn’t scared anyone in my white circle. But now my Bigmama, the family enforcer of Jackson’s racial mores, warned my mother of danger on the horizon.

Mother came from a family with Black neighbors and Black friends, and she laughed off her mother-in-law’s warnings. Same way she’d laughed at me when I returned from my first day of school and declared I knew my left from my right, except I got it backwards (50-50 chance, and I blew it.) Mother had not laughed when I came home and cheered a racist cheer—it even rhymed— the other sixth grade cheerleaders had taught me opposing integration. “Quit that,” she said, and I did. No laughing, either, when I asked why my friend’s mother raised her fists in triumph when Dr. King was shot.

Obviously, Mother reflected her family’s values, but she was also an iconoclast (the same friend’s mother called Mother that, and I looked it up in the dictionary to see what it meant.) That personality trait led her to seek her own path. A certain level of social independence—she had no husband to make her toe the racial line, no job under threat and ten years under her belt away from Mississippi—enabled her to follow it. Now, she was following her new husband into the unknown, with us trotting behind.

After what we children considered an outrageously long honeymoon, Mother and Daddy (nee’ Mr. Van Hecke) returned to say we were moving to Daddy’s native North Carolina. During Christmas break of 1969, with the Holmes order reverberating through Jackson’s white community, we packed up and moved.

North Carolina wasn’t Mississippi.

Don’t get me wrong. My supercilious self did not want to return to Mississippi. While I was in North Carolina wiping off my white frosted lipstick to better fit in, my Jackson friends had jumped like fleas from Bailey Junior High into church gyms and mud-tilted trailers they called “school.” These hastily repurposed spaces were the town’s fledgling segregation academies. Of course, during my summer visit back home, little the-emperor-has-no-clothes me pointed out that a friend’s “school” was where we had roller-skated, not a school at all. But I could only gape when one said she attended Council School—wait, as in Citizens’ Council? The Citizens’ Council, of course, was the Main Street white supremacist civic organization organized to fight civil rights gains, school integration most of all. Chapters were everywhere, but I later learned the group was headquartered in Jackson.

Back then, I didn’t know the word “racist” or “massive resistance” to describe the South’s tooth-and-nail fight against integrating public schools. I knew “white trash,” and I gazed on my friends from my high horse in North Carolina and slapped that label on them. The girls I’d grieved into a mythic tapestry of “the best friends ever,” every single one of them, regardless of income, were reacting to integration shamefully. None stayed at Bailey, none stood up to their crazy parents. Cowards all, I humphed. By then, I was already too proud of North Carolina, too proud of our allegiance to the public schools, Just too damn proud.

In Charlotte, we settled into a low-to-the-ground brick duplex from which we could walk to school. Our neighborhood schools were the cluster of Selwyn Elementary, Alexander Graham Junior High (known as A.G.), and—later—Myers Park High. One summer day, Daddy piled us in the car and slow-drove us through the school grounds, laying out our journey. But the well-laid plans of this man who taught me to love Cheerwine and stan for Eastern-style barbecue were shattered by Federal District Court Judge James B. McMillan.

I never knew Judge McMillan. They say he suffered death threats for his position that racial segregation—a law-imposed creature—must be law-destroyed. Less is said about lawyer Julius L. Chambers whose office was firebombed for his decades-long pursuit of Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education. The Swann lawsuit led to McMillan’s 1970 finding that ending racial inequity in public schools could not accommodate neighborhood schools. It required a “remedial technique” with more oomph. What whites would come to call “forced busing” was about to launch in our new home of Charlotte.

That September, I was still the long-legged, athletic tennis player I’d been in Mississippi, except subdued. I was no longer the chick who arrived in North Carolina wearing platform shoes, my favorite bright blue eyeshadow, and a flouncing mini-skirt. In Charlotte, I was an eighty pound eighth-grader who hadn’t been bused away from A.G., but I missed the cut-off for testing into SAT or even Advanced classes and sat, shell-shocked, in chaotic Regular classes wondering where the hell I’d landed.

Throughout my Charlotte school years, in a herky-jerk manner and typically over summers, the-powers-that-be would redraw the busing lines. Often the red lines ran down the middle of a street: neighborhood schools on one side; hop on the bus and ride on the other. No question, if our house landed on the busing side, I would climb aboard. That was the ethic in Charlotte (though if you read Judge McMillan’s opinions, you see an obstructionist school board intent on protecting, in particular, my white affluent southeast Charlotte.) Anyway, my parents wouldn’t have pulled us from public school. Daddy, whose family had quit the Presbyterian Church when deacons stood on the front steps to bar Black worshippers, believed in his North Carolina’s ability to handle integration.

These summers of waiting were intense spikes on the racial EKG of my youth. My primary concern was whether our friend group would be wrenched apart (it was). Later, at Myers Park High, when rumors of riots flared, the grand experiment became more immediate. But for all Judge McMillan’s good intentions, his “integration” didn’t integrate anything for me. From the day I stepped into SAT classes, my school experience was white.

Except for eighth-grade gym class, my teachers were white. The literature we read was white (I didn’t know Gwendolyn Brooks until I was 46 years old.) Our telling of history—including the story we told about America—remained white. With rare exceptions, I had no Black classmates. At the time, I thought my SAT and Advanced Placement classes had no African Americans for the same reason they had no cheerleaders or football players or freaks: no one was in these classes except for those of us who were. In eleventh grade English, when my teacher verbally pecked at a solitary Black young man as if a foreign egg had hatched in her nest, I never thought, there are no Black kids in these classes because the authorities don’t want them here.

Not once did anyone talk to us about why we were making this massive transfer of bodies. Oh, we knew it was Black and white. But only at Governor’s School the summer after 10th grade did I learn about the gross inequality in public education prior to integration. At this residential program that drew gifted students from across the state, my classes were a mix of Black and white students. In Psychology class, an African American boy and I took to sitting together. While we waited for class to start or loitered after class was over, we talked. He was politically-minded, and in one of our conversations, he told me how his Black public school had to make do with white students’ used text books. “Nasty books, with torn, underlined pages.” He was kind, but frustrated with me, agitated that I was ignorant about the racism that had gotten us into this mess. Apparently, it was easier to move children’s bodies around in the name of equality than to shift our truths.

The chaos of annual reassignments had made me feel as if I were in the trenches of desegregation—arriving at school at seven a.m. because there weren’t enough buses to go around; eating lunch at ten in the morning; watching friends disappear into schools across town. Years later, I realized my focus on the personal had been so complete, I never saw the system.

Yes, Charlotte’s willingness to massively rearrange children to end discriminatory schooling was an eye-popping commitment to the Constitution. And the Charlotte plan worked: schools desegregated and Black students gained access to better school resources. But that wasn’t enough. Both my Jackson friends fleeing integration and my righteous butt seated in all-white classes were caught in the same web of racism spun by our white culture. Now, when I hear myself telling my stock story comparing Mississippi’s disastrous white flight to Charlotte’s model of success (its tag: “the city that made desegregation work”), I shut my mouth.

I have to wonder: if we white folks had recalibrated and faced our racism head-on, would a white parent in 1997 have sued the Charlotte-Mecklenburg school district to void the Swann order? Would the court in Belk v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education have agreed? We’ll never know. The court declared racial balance achieved. The grand experiment ended, and Charlotte schools promptly re-segregated.

In our summers of waiting, we heard tell of a fountain. The fountain was in the woods, I think, the big woods between A.G. and Myers Park. It was circular like a grand Italian fountain with a concrete lady pouring water from an urn. It was open to the public, but you weren’t supposed to swim in it. There might have been an entire park of kiddie rides there, but I’m certain a fountain sat in the shade and you just peeled off your clothes and swam, though I might have made that part up. We went once, a group of school girls of many races and backgrounds. Or maybe my older sister went, and I imagined myself into the group. I do know that when I went looking for the fountain in my dreams, it wasn’t there.

Ellen Morris Prewitt practiced law in Jackson, Mississippi, for 19 years. She is now an award-winning short story writer, essayist, radio commentator, and novelist. Her current work— a novel about reparations for victims of Mississippi’s Civil Rights era violence—recently placed in the William Faulkner Literary Competition. She divides her time between the Mississippi Gulf Coast and New Orleans, where she can often be found in costume.