By Stuart Levin Beeson Academy Hattiesburg, Mississippi 1976-1977

I spent only one year at a seg academy in Mississippi, but don’t think any other year of my K-12 education had a more profound influence on my life. Entering tenth grade in 1976, my perspective was that of a Yankee outsider. We moved from suburban Philadelphia after my father (who worked as a clothing buyer for the discount department store chain Value Mart and commuted daily to New York City) was transferred to the home office in Hattiesburg. As a Jew growing up the Northeast, no one I knew would have considered transplanting to a small town in the Deep South a positive step. While TIME magazine had a cover story that year trumpeting the New South as Jimmy Carter ascended to the presidency, Mississippi remained the “thank God for Puerto Rico” state. In fact, my mother was so embarrassed about the move that I was forbidden to tell anyone in advance.

The contrast between my old school and the options in Mississippi could not have been more stark. In a state where the minority community comprised over one third of the population historically attending schools both separate and unequal, the public high school had experienced an exodus of white students after integration five years earlier. Beeson Academy served as the escape valve for those white students. The rationale behind Beeson’s founding was unambiguous, and not based on academic excellence.

Mississippi had never been generous in funding its public schools, and integration only further undercut these expenditures. As I soon found out, the disparities in school district funding between states were reflected in the quality of the curricular options. According to the US Department of Education, per capita spending per pupil in 1976-1977 (in constant 1995-1996 dollars) was $2770 in Mississippi vs. $4445 in Pennsylvania. The academics offered at my new home reflected this gap, and were hardly equivalent to the standard tenth grade college track classes in Pennsylvania. No high school (public or private) in Hattiesburg taught Algebra II or chemistry before eleventh grade or languages above introductory French and Spanish. Additionally, there were no school orchestras. But Hattiesburg had an advantage over other towns in the state as the home of the University of Southern Mississippi.

The Hattiesburg Public School District proposed I go to three schools in order to further my education where I had left off in Pennsylvania-the old black high school (the new tenth grade learning center), the old white high school (now eleventh and twelfth grade) and USM. The Beeson option involved only two schools—morning at Beeson and afternoon at the university. In the name of pragmatism, Beeson became my new high school. Going to three different sites in one day would have been logistically impossible without a car (or for that matter a driver’s license). My parents weren’t thrilled about my attending a nominally Christian school but were committed to making sure I was able to get a good education. And at least my dad could take off from work during his lunch hour to drive me from Beeson Academy off Highway 49 in south Hattiesburg to the university north of Hardy Street.

I do have some fond memories of Beeson. My new school was smaller and more hospitable than I was used to. I was able to make some quick friendships. I enjoyed my classes since eleventh grade English and chemistry as well as twelfth grade math were on par with the tenth grade curriculum up North. I wrote for the Trojan Tribune, and learned to type on an IBM Selectric (later proving more useful than I could have anticipated at the time). And my unusual schedule allowed me to place out of PE, never my strong point.

Just below the surface, there was an unintentional (and mostly unilateral) cultural exchange. I learned to speak Southern though my accent always gave me away, and referred to the War Between the States (War of Northern Aggression was a bit of a stretch). My classmates exposed me to hayrides and revivals, I grew to appreciate sweet tea, fried okra and pecan pie, and had my first experience in a (somewhat rowdy) college dorm staying at the Ole Miss twin towers for a math and science conference. While morning prayers were mandatory at school, my parents insisted I be allowed to opt out of publicly reciting New Testament verses. Nonetheless, I was being given the opportunity to find true salvation. Indeed Beeson had admitted me as well as several other Jews, so wasn’t I one of the chosen people?

Of course, chosen in Mississippi meant not my church but my pigmentation. The small merchant-dominated Jewish community navigated a fine line between the races. As I later learned, the temple leadership had fired an outspoken rabbi 12 years earlier when he took a public position supporting the “outside agitators.” And other than going to the “Jewish church”, I was fully accepted at Beeson.

I wanted to get along with my peer group and had no particular aptitude for being outspoken. Yet the more I learned about Mississippi, the more questions I had about my new home. The miniseries Roots was the talk of the nation that year, but at the same time I realized that at Beeson some thoughts were better left unstated. I lacked the moral courage to respond when my teachers spoke about “Negroes” (an anachronism by the mid-seventies) in a drawl uncomfortably close to the N- word. After all, Mississippi history at Beeson was still taught from a 1964 public school textbook that blamed “the presence of the carpetbag element and the bad conduct of the Negroes” for the troubles during Reconstruction, and showed adjoining pictures of “modern Negro” and “our newer school buildings” (i.e. white). I wish I could say I was more open in resisting the prevailing mindset although that would not be true.

But I did find a sort of salvation in the daily shuttle between the academy and the University of Southern Mississippi. My dad would pick me up at lunch from Beeson (always in time for Paul Harvey on the radio) and bring me over to the university. I would spend the afternoon at Southern in classes, studying in the library or the language labs and practicing violin in the music rooms (where I took lessons and played in the orchestra). I sometimes stopped by the Student Union prior to heading out towards Hardy Street for the two-mile walk back to my house.

USM became my window to unconsciously counteract the segregationist environment at Beeson. Beeson was not officially called a seg academy, but we all knew what it was. By contrast, the dynamics at the university were different from speaking with my Beeson classmates and teachers. I felt bold enough to engage in difficult conversations. I had never been on a university campus before and was the youngest student there. The age difference with other students made me a bit of a curiosity in a non-threatening way. At Southern I could talk with co-eds from rural Mississippi on their own journey away from home. Most of them had graduated from seg academies similar to Beeson but at least some were interested in exploring a wider world. I learned from professors happy to share their life experiences. And importantly, USM had (marginally) integrated by that time.

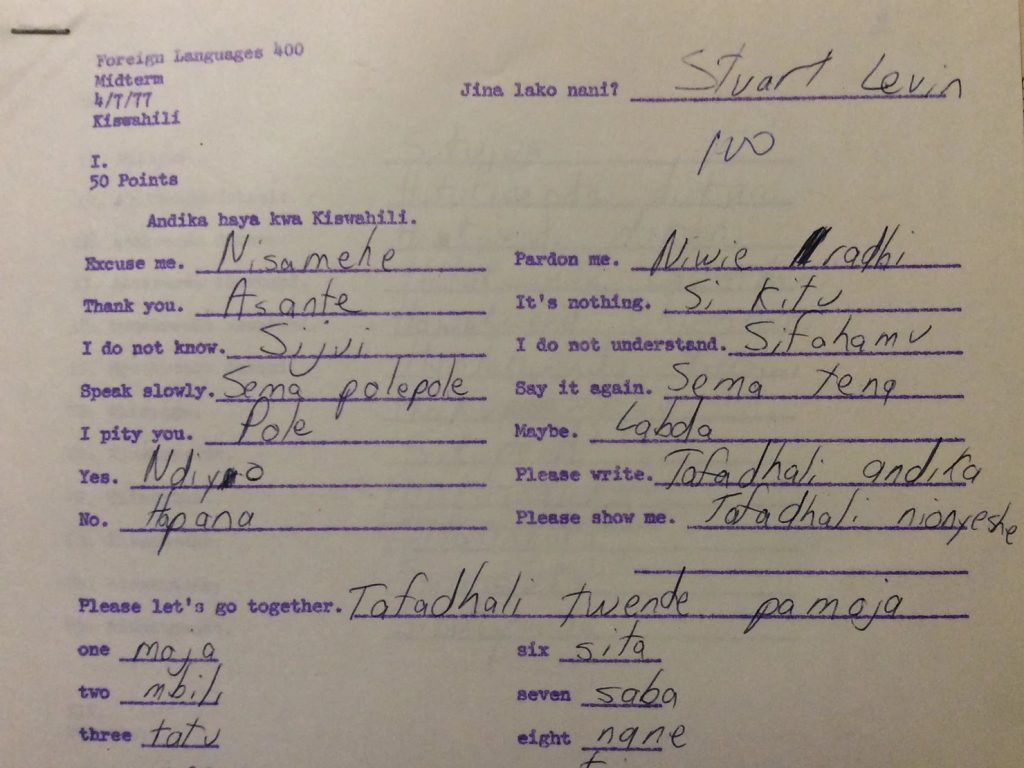

The lack of foreign language instruction at my high school led to the kind of cultural exchange that Beeson had been founded to avoid. Over the fall and winter sessions I enrolled in advanced French and introductory German at USM. Dr. Johnson, the chair of foreign languages, subsequently recommended that I join one of his other classes: the first Swahili course (opaquely titled “Introduction to Exotic Languages”) at a predominantly white university in the state of Mississippi. I doubt Dr. Johnson knew much more Swahili than the students. But this class offering was a political statement as well, an African Studies course that drew interested black students. I was in a minority of white students in the class, which provided space to discuss the daily challenges of being a black student on a mostly white campus.

Furthermore, taking courses at USM gave me an opportunity to address questions about the state that I was reluctant to ask at my high school. After spending several sessions on campus I found an opening to get credit that summer enrolling in a class on Mississippi history. We were assigned readings that did not gloss over the most troubling aspects of state history, including biographies of virulently white supremacist Governors Vardaman and Bilbo. Dr. McCarty at USM encouraged me to explore primary sources. I spent countless hours in the archives of the Hattiesburg American researching the fight against attempts to integrate the local public schools. The contemporaneous newspaper accounts were compelling for their open racism just below the patina of Citizens’ Council respectability, rarely if ever giving the perspective of the black community. Given that the events had only occurred a decade before, many of the names were quite recognizable (including Mr. J. A. Beeson). Both the highs and lows of Mississippi history were confronted in that classroom. Dr. McCarty’s course truly set a standard for encouraging critical thought including questioning basic assumptions.

My dad changed jobs the following year, and we never returned to live in Mississippi. But the impact of my time at USM remained. I stayed in the South, and six years later received my undergraduate degree concentrating on Southern history at Duke University, where Dr. McCarty studied for his PhD.

Some of my other experiences that year stayed just below the surface until Sen. Cindy Hyde-Smith’s 2018 campaign resurrected them. I don’t know her personally but do know that for a year we shared a similar path, students at Mississippi academies less than 60 miles apart. And I suspect she also might have benefitted from some difficult conversations.

Stuart Levin is an internist and clinical professor at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine, as well as a community activist focused on population health. He lives in Raleigh, North Carolina.