Jackie Jones Clowney, Briarcrest Christian School, Class of 1985 Memphis, Tennessee

Until reading The Academy Stories and having discussions with friends who attended private schools beginning in the Seventies, I was sure that my Tennessee school was not a segregation academy. After all, “Academy” appeared nowhere in its name. We were simply a “School,” albeit a Christian one. But then why would my father send us to a Christian school? He was not a Christian, at least not a practicing one. He’d never come to church with us, not in all the years my mother attended the Methodist church religiously, bringing my brother and me along as well.

If that Christian education was so important to my father, then why had he allowed my older brother, John, to attend public school for nearly three years, pulling him out midway through his third grade year at Sea Isle Elementary in Memphis and enrolling him at Briarcrest Baptist School? Upon John’s departure from Mrs. Bean’s third grade class at Sea Isle, his fellow students wrote letters to him; letters of farewell, letters wishing him well, and letters telling him how lucky he was. I always wondered why they thought him lucky.

Bussing, in order to further desegregate schools, started in Memphis in 1973, the year John was in third grade. Briarcrest Baptist School System started the same year, going on to become the biggest private school system in the country, it claimed. While my father removed John from public school and sent him to Briarcrest, I never spent a day in a public school classroom.

As I watched the film The Blind Side a number of years ago, I realized that Briarcrest was the school featured in the film even before the credits ran and showed the Saints uniforms in the photos of the real people that the characters were based on. I was pretty peeved that the school, my school, had not allowed the filmmakers to use their name or likeness. After working in marketing for a number of years, I thought that Briarcrest had just foregone the best piece of free advertising they could ever have while still sending out donation requests to alumni. A fellow alum told me that they disallowed use of the school’s name and image because the Coach Cotton character says the word “shit” in the film. I have heard Briarcrest coaches use curse words far worse than that.

Why wouldn’t Briarcrest want to show themselves to be community minded, giving a low income, black student a chance at an education? Why wouldn’t they want to show their students’ parents to be giving, caring people who did something seemingly selfless for someone who had less than they did? Why wouldn’t they want to show their faculty and staff encouraging and lifting a student up? I realize that this was a fictionalized account of a true story and that not all elements in the film are fact, but the fact is Briarcrest lost an opportunity to show itself as reformed, evolved, better than the original premises upon which the school was founded. Maybe they understood that some parents were still sending their children to that Seventies-era school, aware that the school had originally provided an all-white shelter for white children.

I spent first through twelfth grades at Briarcrest, but I don’t think I was aware of the racial divide in the schools in Memphis until 1983. It was an unseasonably chilly and overcast March day. My friends and I sat on the cold concrete under the portal where students were protected from the weather when their parents dropped them off and picked them up from school. There was a large parking lot that stretched to the street where driving-age students parked their Ford Broncos, Mazda RX-7s and Volvos. The school did provide bus service, but kids who rode the bus were dropped off and picked up behind the building. Maybe no one wanted see buses. No one wanted that reminder. Buses were ostensibly why a lot of us were there, although I know now it was to avoid going to a an integrated school.

We usually didn’t have to wait in line for tickets to attend basketball games, but this was the first round of the AAA Division High School Basketball Tournament. Briarcrest’s all-white team was to play at home against Northside High School, an all-black team. We had played all-white teams during our regular season—other private schools and county public schools further down the highway of white flight that were not affected by inner-city busing.

Briarcrest was mandated to provide a certain number of tickets to Northside students and their families, which meant there was a limited number of tickets for us. My father’s opinion about black families and students being allowed in our gymnasium fluttered back and forth between calling it a joke and being completely outraged. The idea that I might not even get to go to a game against a black school was floated.

My mother said it would be a shame if I didn’t get to see our team win and go on to the state championship. “Win?” my dad questioned. “Please. Don’t go thinking we’re going to win this game.”

A voice over the P.A. system at school the morning of the game explained that Briarcrest students were to be welcoming and show “them” how to behave. I knew exactly who “them” were. Although it is a perfectly good pronoun and is used in the article from the Memphis Press Scimitar in a seemingly benign way, I still can’t read that word and think anything besides “other” in that context.

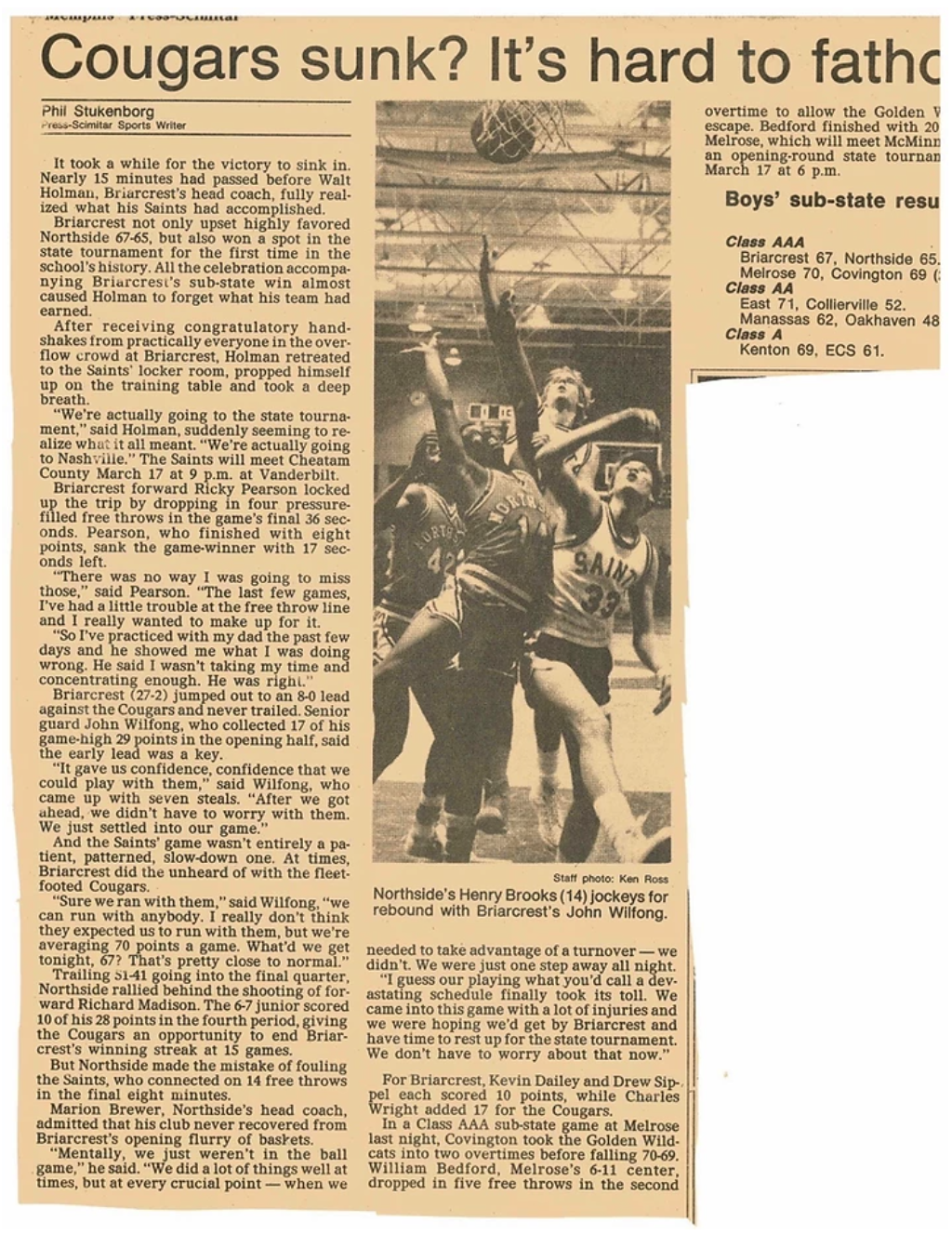

There was additional security at the game, but once the game started no one really noticed. We took an early lead, and it never let up. We won, leaving our coach so flabbergasted that he still couldn’t believe it two days later when I had him for fifth period. He called me over to the small table which he used as his desk in the balcony of the sanctuary where we met for study hall. I wasn’t sure what I’d done. I talked a lot in study hall, but Coach never really got on to me. He was a lot nicer to the girls, where he was pretty much a hard-ass to the boys. He showed me the picture on the Memphis Press Scimitar sports section front page of our basketball players jumping for joy, incredulous that they had just won a game nobody said they could win. You couldn’t beat them at their own game, people said. They were superior athletes, you know. God had to bless them with something, didn’t He?

Coach pointed to the corner of the photo, to a girl in the stands—a girl jumping so high that her feet were higher off the ground than even the players’. “Is that you?” he asked. When I said it was, he said “You should play basketball, you know.”

The Briarcrest Saints did go all the way to the state championship game that year. We lost to Melrose High School—an all-black team.

Jackie Jones Clowney holds a B.A in English Literature from the University of Memphis, an M.A in Liberal Arts from St. John’s College, and a M.F.A. in Creative Writing from Mississippi University for Women. She lives in Santa Fe, New Mexico with her husband.