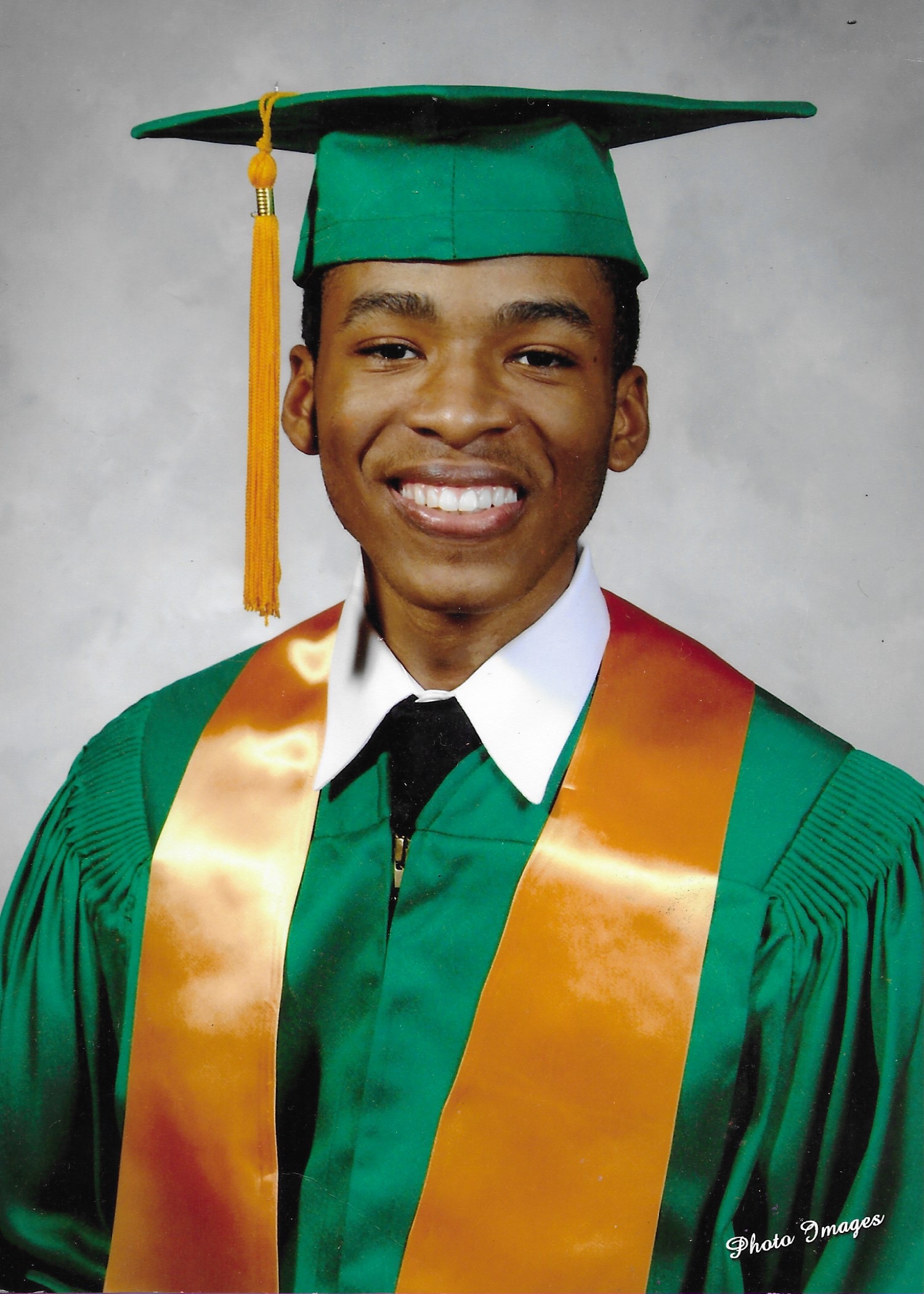

Jehrod Rose-Alain Jim Hill High School, Class of 2007 Jackson, Mississippi

I was born on the west side of the tracks. Raised and educated in the capital city of Jackson, Mississippi, I played and went to church more often than not. I didn’t have many friends, but I had three younger sisters who were constant playmates whenever I tired of my solitude. Together we had to learn the 23rd Psalm and the books of the Bible in their respective order. We had to say “yes ma’am” and “no sir” and always address adults with respect; it was the South, after all. Sunday School was the foundation of my education, and let’s not forget the many Easter speeches throughout the years. I was a star at those. One of my earliest memories is my grandmother teaching me the alphabet. “Start again”, she would say whenever I messed up. A sturdy pencil was there to meet the inside of my tender palm with a sting if I missed just one.

My Jackson Public School trek began at Barr Elementary, a school flanked by heavenly cherubs and the most magnificent brick. There I participated in school plays and in the choir and had the most wonderful teachers. Afterwards, I briefly attended Blackburn Middle School. I still remember the four months I was there because of the weight of the cello against my shoulder. An all-black school, Blackburn gave me a way to see myself creatively because my education was buttressed by the arts. The following December, Mom was hired at MCI Worldcom, and her supervisor salary allowed us to move from her parents’ home in West Jackson to a lovely white clapboard, four-bedroom home in south Jackson. With that move came a change of schools and more lessons than I cared to have.

I entered far whiter Whitten Middle School. My teachers were mostly white. The student body was diverse, but I had never been around that many white students before. This is when whites still lived in south Jackson. They had not yet become caught up in their proverbial white flight and didn’t mind sending their children to public schools. At school, I do not remember feeling inferior or facing overt racial discrimination—I’m getting to that— but my family received backlash from our white neighbors.

Mom opened the door one morning to find a dead squirrel placed squarely on our welcome mat. She remained calm as she told us, but it was a lesson in just how uncivil some people can be and a ghastly chore for me. My stomach turned, and so did my heart at the idea of an act that malicious and so likely racist in our new neighborhood. Never one to retaliate, but to further prove her point, she had my grandfather, one of the best landscapers in Jackson with wealthy, white clientele throughout Woodland HIlls and Madison, to adorn our yard with roses and azaleas sculpted so pristinely they could be the envy of English-style gardens the world over. Her point? We belonged there. I can still see the three, egg-shaped boxwoods he sculpted in a way Michelangelo would have if he had been a black landscaper in the twentieth century South and worked with leafy perennials instead of marble.

This was 1999. Before the turn of the new millenium. This was also the school year JPS implemented the Exit Test— a test meant to ensure that before a student went on to the next grade level, they show mastery in English, reading, math, and science. Well, I did not pass that exam, which floored me. Was it because I switched schools? Or was I just not as smart as my grandmother believed? I didn’t see it coming because my grades were good. I had to repeat the sixth grade because of it, and even after completing a summer session and retaking the God-forsaken test, I was retained. I’d never had trouble before, nor had I had bad grades at Whitten.

Was the cup half-empty? Who or what had failed me? Or was it I who was broken? Looking back, I wonder about the reality of the soft racism of low expectations. Had white teachers shuffled me along, since my grades didn’t match the outcome of the test? Were the teachers that disinterested in whether I could actually pass the exit test or not? Looking back, I didn’t thrive in white-predominated Whitten in the way I did before and after in Jackson public schools where more teachers looked like me.

I must say that before I left Whitten, I was deeply influenced by my eighth grade English and Language Arts teacher, Mrs. Doris Still. She influenced the reader in me, was loving and genuinely saw me. I was so influenced by her that I entered the district’s MLK “I Have a Dream” contest and won second place. Mrs. Still stood out, I think, as the exception who proved the rule at Whitten, though.

Then 9/11 happened, and the world changed forever. The sense of fear was pervasive. I remember the long gas lines after Mom picked us up from after-school care and the serious “give your life to Jesus” talk that happened after dinner, followed by prayer and congregational songs. Almost a year later, Mom would succumb to breast cancer at 33, and my personal world tower would come crashing down. The acrid smell of cancer burned my nose like the billowing, white smoke and the singe of burning flesh on that unforgettable September day in Manhattan.

Jim Hill High School redeemed my inner city school experience. Not only was I able to stay there all four years, but I was stretched and challenged. My freshman year was full of high marks and teachers like Mrs. Sharon Summers who challenged me to be my best. She was my biology teacher and because of her I would go on to be accepted into the biology honors program called S.O.A.R— Student Oriented Academic Research. Jim Hill was unique because of programs like this one, but especially for being an International Baccalaureate school — the only one, might I add. I was not a part of the program, but still benefited from the exposure and the Advanced Placement classes I took.

I excelled in my English and science classes, but failed terribly at math. My math teacher, David Molina, became a hero for me. He believed in me and taught me to see numbers as words to be read, as he knew I had a deep affinity for reading. He affirmed me, and even though I never made anything higher than a C in his class, he still would tell me how intelligent I was. “Intelligence is the ability to adapt in any situation you’re in, Jehrod.” Mr. Molina held everyone in his regard, C students no less than the class stars. That wisdom has stayed with me all these years. A recent graduate of Amherst College, Mr. Molina was there because of the Teacher Corp program sponsored by the University of Mississippi. I think being at Jim Hill was as much of an education for him as it was for us. He left an indelible mark, and remains a mentor and friend to this day.

In fact, his support makes me look back even more critically at my lacking and debilitating experience at Whitten and how it made me question my intelligence and stop believing in my potential. Looking back, I firmly believe that teachers who looked like me were more invested in me. They cared and were not afraid to chastise me and challenge me to reach deeper and think more critically. These instructors, Mr. Molina included, were the catalyst for my advancement.

Some students, like myself, need the arts to make sense of other subject areas. I was in luck at Jim Hill. The apex of my high school experience was the musical training and traveling experiences granted by being a part of the world-renowned Jim Hill High School choir under the direction of Mr. James Hawkins. Always in a white dress shirt that was tightly tucked and a belt he grabbed every time he stood up behind the piano, Mr. Hawkins took music seriously and treated us like adults who were expected to show up and be ready to work. “Commitment to Excellence” wasn’t just our choir motto, it was the very cloth from which we were cut. From learning to sing in Italian, Latin, French, among other languages, we also sang sacred songs like Regina Coeli by Pietro Mascagni and spirituals like Joshua Fit the Battle of Jericho in the African American musical tradition. It’s no wonder we always came away with superior ratings in competitions and endless invitations to sing around the world, including Vancouver, Canada, Honolulu, Hawaii, and Ponce, Puerto Rico— trips I was fortunate enough to take.

The education I received at Jim Hill was well-rounded. I was inducted into the Jim HIll Hall of Fame and was voted “Most Likely to Succeed” and “Most Intellectual” by my peers. In fact, I even gave the farewell address for my Class of 2007. Jackson Public Schools did not fail me. Could my education have been better if the state fully funded public education? Absolutely, yes. Would it have been nice if we actually had textbooks? Most definitely. I wasn’t aware that most of my white contemporaries in Jackson were in private schools.

We have to do all we can to ensure that inner city youth like myself can have a fair shot at life. Without the arts, strong mentors as well as teachers, and learning opportunities outside the traditional classroom, this is next to impossible.

In this new digital landscape, I’m even more afraid for the black and brown students that make up JPS. Laptops have replaced textbooks all together, and because of Covid-19, I’m afraid they will have to fight even harder for the quality education they deserve.

Jehrod Rose-Alain is a writer in Jackson, currently completing his certification as a yoga teacher. He attended Tougaloo College. He is a lover of all things French and of coffee.

Love, love, LOVE this Jehrod! I can’t wait to read more of your writings.