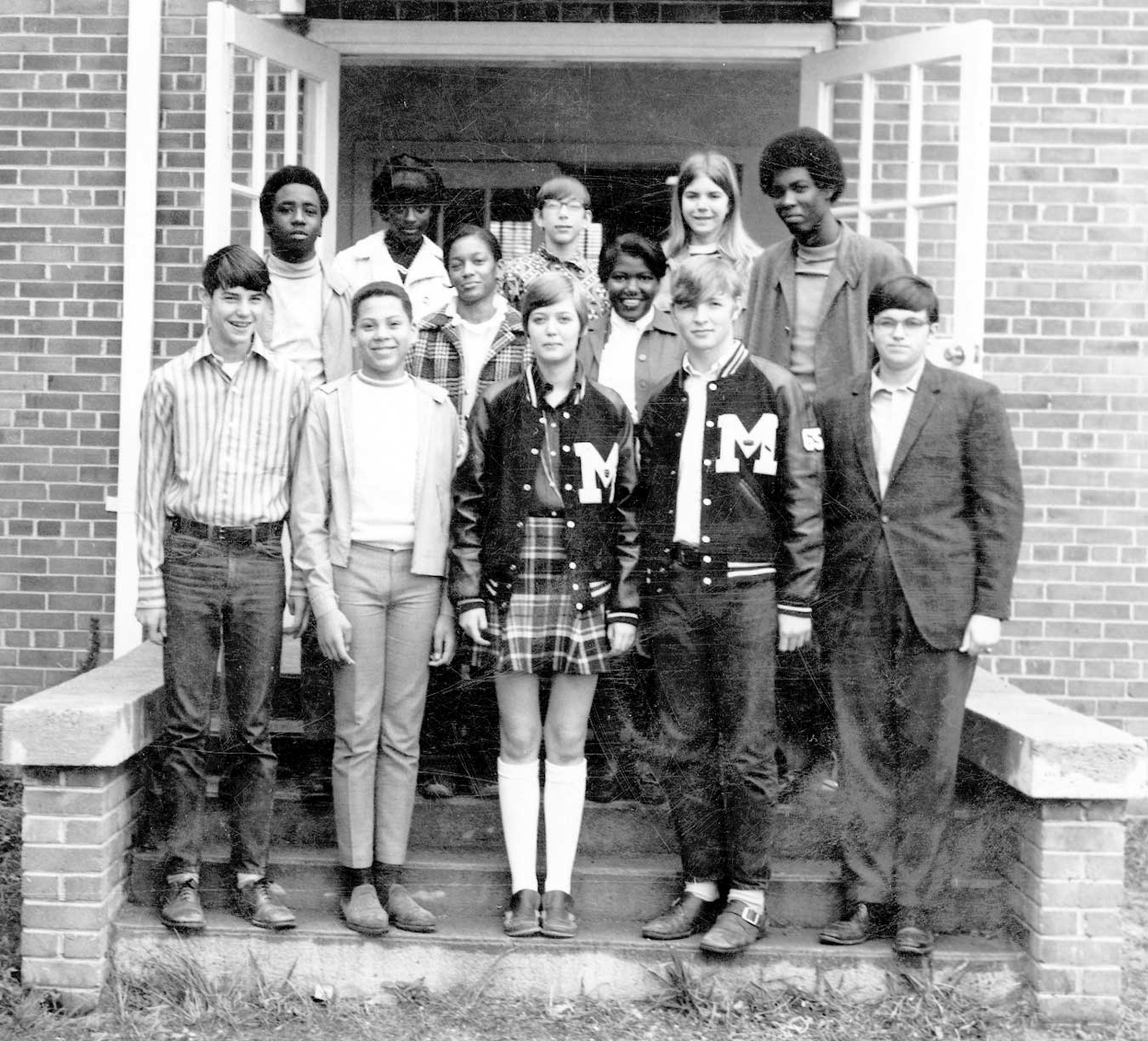

W. Ralph Eubanks - Mount Olive High School - Class of 1974

On the edge of the small town of Mount Olive, Mississippi, stands an anonymous red brick building that is now a flea market. Right near this lonely-looking bazaar stands a sign proclaiming that Mount Olive is the home of football great Steve McNair. While the building is now of unknown origin to many in my hometown, I remember when this place that now looks like a deserted ranch house held a small measure of mystery and menace. It never had a sign outside telling us what it was, but we all knew its purpose.

Before Freedom of Choice allowed black students to attend integrated schools in my county in Mississippi, the building was empty. Then, before the first black students walked through the doors of what black folks simply called “the white school,” it became a school. And given that this is Mississippi, you’ve probably already guessed that it was an all-white segregation academy. There was never a visible marker proclaiming the name of the school or anything else to let the public know that this was an institution of learning. It was just unspoken in my town that this was a private school, one that through its anonymous presence marked it as “whites only.”

There were very few black students who chose to attend the school “over town” as we called it. No more than a dozen black students attended Mount Olive School under freedom of choice, and I remember the ones who left Lincoln School—the black school—in the mid- to late-1960s to integrate Mount Olive. The black students who attended ranged from fourth grade to high school. Some lasted a few years, some lasted only a semester, a few graduated from there as the only black students in the class. Those black students who returned came back with stories of neglect and mistreatment that were painful to hear. My parents debated whether to send us to Mount Olive under freedom of choice, but in the end decided against it because they were concerned with how we would be treated. I am grateful to my parents for their prescience.

While I’ve never known who founded the first private school in my town and could not tell you when it closed, I do remember this: there were more students who migrated to that private school than black students who integrated the school under freedom of choice in 1966. At the time there was a great deal of political rhetoric among whites discussing maintaining “quality education” in Mississippi schools, a euphemism for maintaining segregation. This shabby building did not look like a place that could possibly give those students the quality education they were seeking, only one without a black student a few rows across from them.

Freedom of choice was a strange phenomenon that placed the onus of integration squarely on the backs of black families. It was also a system that assumed people were actually free to choose, one that my mother famously dubbed “giving white people the freedom to destroy you.” Looking back on it, it reveals the racial dichotomy that exists in this country on how whites and African Americans define freedom. For whites, freedom is something that you possess by birthright and that you fight against when you feel what you have defined as freedom—and that can be defined almost anything—is being taken away. For African Americans freedom has always been aspirational, something to work toward, but also something conditional that can be taken away at any moment. The resources many all-white schools possessed seemed to offer a chance to grip tightly an aspirational form of freedom. In many white schools there were college preparatory classes and other resources—labs and up-to-date textbooks—that were not available in black schools. It was no secret that separate but equal was never truly equal.

After federal courts deemed freedom of choice just another means of maintaining segregation and schools integrated in Mississippi in 1970, each year every school had a few empty desks. Without a law mandating compulsory school attendance—the 1918 law requiring school attendance was erased from the books in the wake of the Brown decision in 1956—every year a few people simply dropped out of school and migrated into the world of work. But after integration, another form of ghosting of the school system began. That was the migration to segregation academies, many of them larger than the little one in my hometown. Just as black students disappeared from Lincoln School to integrate Mount Olive, whites slowly migrated to an academy just twenty miles up the road in Simpson County.

It’s been more than forty years since my high school days, but I still remember the names of the kids who were yanked from my public school and sent to Simpson Academy. Perhaps the reason I remember this so well is that they were the children of business owners in the community, and these came to be businesses my family no longer patronized. My parents’ position was, if they aren’t good enough to go to school with you, they don’t deserve our business.

To this day, this migration of my fellow students to private academies makes me feel both confused and angry. None of my classmates who left were unkind or tried to keep a distance from me or any of the black students. Perhaps it was their seeming embrace of integration as normal that led their parents to move them to a segregation academy. From my perspective it was a decision motivated by fear, not of the kids but of the parents.

Looking back, what led to my bewilderment and anger was that every day I experienced how the burden of integration fell squarely on the backs of black students. From the day black students walked through the schoolhouse door, we were treated as unwelcome interlopers who had to prove ourselves worthy of just being there. Our arrival was greeted by protestors carrying brooms and mops, telling us that they would clean us out of the school like trash. There is little I remember of that day, except for the rapt silence of my siblings and I as we went to school that day. But there was one thing we knew from that moment on: We had to be better than the white students. As the son of a teacher I felt that pressure intensely.

The memories I have of high school tend to flashback to the emotional stress and strain brought on by that struggle to be faultless in my work and impeccable in demeanor than the few isolated genuinely happy moments, which largely took place outside of school. Given my intense unhappiness in school, I counted the time until my graduation much like a prison inmate. Yet the fact that white people felt they had to escape being around me, as if I had somehow tainted their learning environment, made me angry. It still does. The parents of my fellow students who pulled them from integrated schools often did it because they felt they were rescuing them from my presence and my blackness, which was viewed as menacing and unwelcome. Those whites who wanted to could escape, which seemed cowardly since we all knew the pressure was not on them. My only choice and the choice of every black student was to stay and feel trapped.

“Do I want to be integrated into a burning house?” That is the question James Baldwin posed so provocatively in his 1963 book The Fire Next Time. None of us wanted to be trapped inside the burning house of school integration fifty years ago, but the truth is the house never really had to burn. Those who fled Mississippi’s schools, first to academies and later to Christian schools—many of them no more than segregation academy version 2.0—allowed it to burn by abandoning public education. An integrated and inclusive education could have helped extinguish the embers of the un-redressed legacies of Jim Crow, fires that are still burning today. Private academies merely helped foster the segregated cultural memory and the lack of understanding of how the remnants of our segregated past still lives among us all.

Very few people in Mount Olive remember that the flea market on the edge of town was once a segregation academy. The memory of Steve McNair’s NFL career looms larger. Maybe it is a good thing that the legacy of a black football great that unites the town now overshadows a building that was once housed something that existed to divide us from each other.

W. Ralph Eubanks is the author of Ever is a Long Time and The House at the End of the Road. His next book, A Place like Mississippi, will be published March 16, 2021. A 2007 Guggenheim Fellow, he is currently a visiting professor of English and Southern Studies and writer-in-residence at the University of Mississippi.

Thank you, Ralph. You have been a bright light for decades. Shine on!

Thank you, Ralph. An eloquent, truthful recounting of very hurtful times. I’m so glad you did it.

Well said, Dr. Eubanks. I wonder how some of the other students experienced it.

As a 70 year old white woman who graduated high school in Waynesboro, MS, I can feel the pain you still have in writing about your high school experience. I am thankful to have lived in the Atlanta area for the past 40 years and am truly enlightened about the atrocities of racism in the south in the 50’s and 60’s. Thank you for sharing your story. I look forward to reading more of your writings.