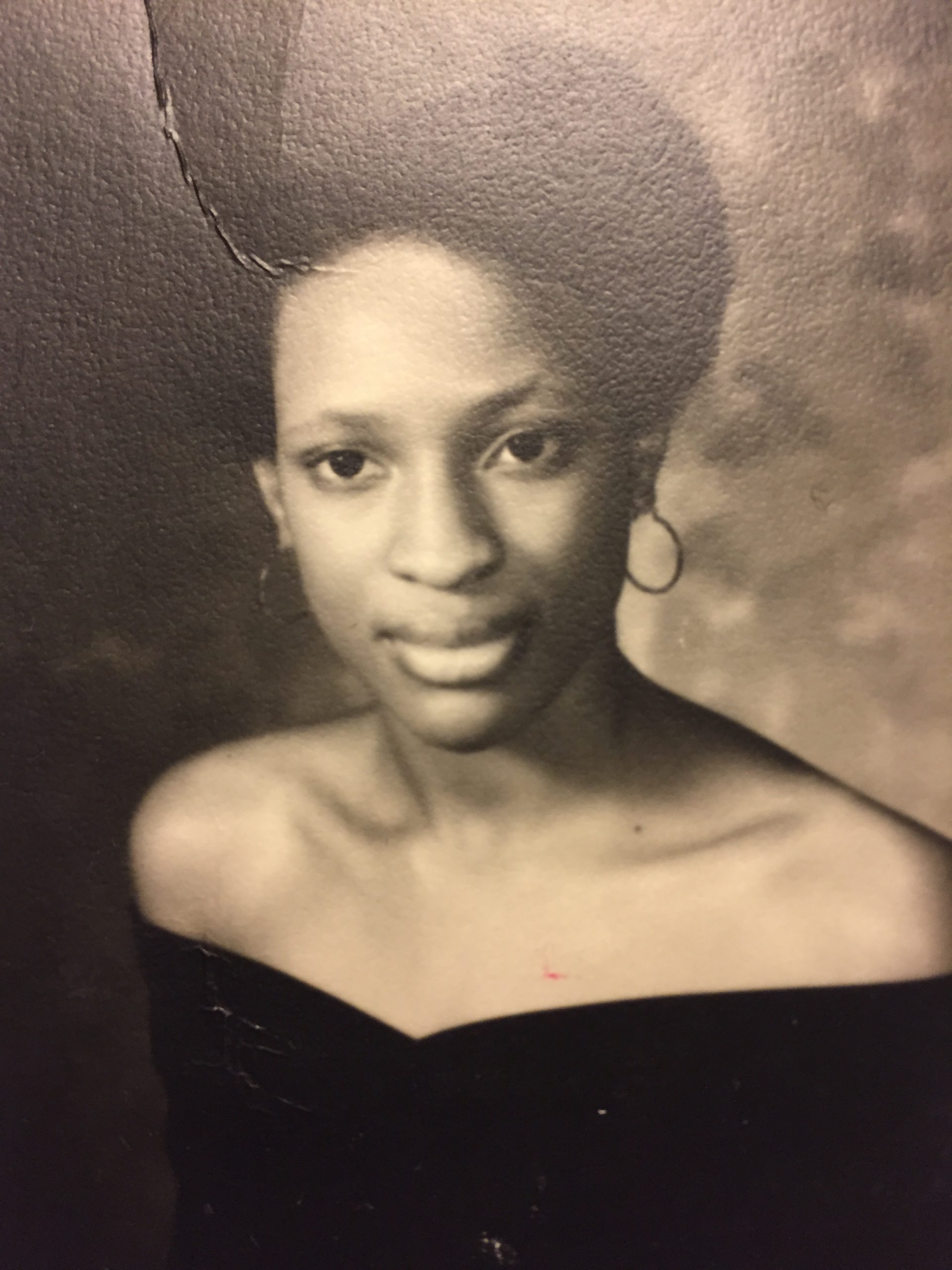

Paulette Boudreaux Oak Park Elementary, 1960-1964, Laurel, Mississippi Sandy Gavin Elementary, 1964-1966, Laurel, Mississippi Oak Park Junior High, 1966-1967, Laurel, Mississippi Liberty Junior High, 1967-1968, Liberty, Texas Liberty High, 1968-1969, Liberty, Texas Oak Park High, 1969-1970, Laurel, Mississippi Balboa High, Class of 1972, San Francisco, California

“The only thing standing between you and this life I’m living is education, and Lord knows, you don’t want the life I got.”

The first time I heard this from my mother, I was seven years old. I had just arrived home from school, late. The pink cotton dress that she had starched and meticulously ironed for me, now had pale splotchy mud stains on the front of it because I had been persuaded by my 12-year-old cousin to accompany her to the woods behind the school to collect the earthworms languishing in shallow puddles left by an early spring rain. The plan hatched by my cousin was that we would detour from our path to school the next day and go fishing, using those earthworms as bait. Somehow, my mother had gotten wind of our scheme.

While I was much too young to understand exactly what was so awful about the life my mother was living, the pain and fear radiating from her eyes was enough to make me dread the future her expression seemed to portend.

My mother’s life at the time was that of a working mother with three young children (me being the oldest), and an illiterate farm laborer husband. This was the early 1960s and my mother worked as a maid for three different white families in our segregated Mississippi town. She earned three dollars a day. Her husband, my stepfather, worked on a poultry farm, earning not much more. Even with their two salaries, they barely made ends meet for our family.

I knew my mother had graduated from high school, and it was not lost on me that a high school diploma had not gotten her very far. My stepfather hadn’t made it past first grade. He signed his name with an X. In later years, I noted the shame on his face, when my mother wasn’t nearby and he had to ask one of us children to read some paperwork for him or read a notice or the name pasted on a building. He leaned pretty heavily on the value of education as well, though he was less vocal about it than my outspoken mother. Over time, I came to fully understand their attitudes toward education, and I knew I would need more.

My educational journey had begun two years earlier with kindergarten. Somehow, my family scraped together the fees to enroll me in a private kindergarten taught by black educators and housed in the basement of one of the more prominent black churches in my hometown, Laurel, Mississippi. It is only in hindsight that I recognize the sacrifice this expenditure must have meant for the family. All I knew at the time was that I entered first grade already knowing how to read and write and do simple arithmetic.

My private kindergarten class had been all black, and though Brown vs. The Board of Education had determined in 1954 that segregated public school systems were unconstitutional, the schools in Laurel in the early 1960s were still very much segregated—all black on one side of town and all white on the other.

I moved through grade school at Oak Park Elementary and Sandy Gavin Elementary and the first year of Oak Park Junior High in the strong embrace of my segregated black community where education was valued and fostered in a system where everyone looked like me—the other pupils, the teachers, administrators, principals, vice principals, the janitors, everyone. Everywhere I turned, I experienced echoes of my mother’s sentiments about education—it was the way upward.

Our teachers were relentless in their efforts to elicit our personal best from us, taking no excuses for poor grades, sloppy schoolwork or ill-mannered behavior at school. While there seemed to be an awareness by most of the teachers that some children were less gifted or capable intellectually than others, and there were clear socioeconomic distinctions in the student population—our humanity was never in question. We were all pushed, cajoled, rewarded, encouraged, lauded, and made to toe the academic line according to our individual abilities as they were perceived.

Because we were all of one community, communication flowed easily between teachers and parents. Sometimes the fact that my mother would likely run into a teacher of mine in church or at the grocery store was more of a curse than a blessing. One year I discovered my teacher had gone to the same rural Mississippi school as my mother, much to my chagrin. It meant that any tendency toward laziness with my schoolwork or loosening of personal deportment at school could be promptly conveyed to my mother. I would be called to task at home as well as at school.

My academic world changed with eighth grade. Voluntary integration had been an option in the public school system for a while. Really what it meant was that black families who wanted to do so, could send their children to the other side of town to attend white schools. Not very many black families were willing to take the town up on that offer, aware as they were of the unkind prejudices that awaited their children in the white community. But some black families did.

My family had tossed around the idea when I entered seventh grade. But from years of venturing to the white side of town to work in white households, my mother knew the lay of the land with regards to most local white families’ attitudes about black children in school with their white children. My mother worried about my safety. She weighed the risks of sending me, a wispy and stubborn 12-year-old, alone to the white side of our Mississippi town. Ultimately, she decided against it, though the popular belief was that a better education was to be had in the white schools.

However, my paternal grandparents lived in a tiny segregated town in south central Texas where voluntary integration was also the response to the U.S. court’s desegregation mandate. A female cousin, who was my age and in the same grade, lived with my grandparents and had attended the white school for her seventh grade year. Everything had gone well enough, according to our grandparents. Their thought was that Texas was less racist than Mississippi. So, the adults in my world made the decision to send me to Liberty, Texas to live with my grandparents to get a better education by attending a white school.

I started my eighth grade year as one of a handful of black children, along with my cousin, attending the white school of several hundred pupils. I went with a mixture of excitement and apprehension.

The situation I entered was unlike any of the years of my early education, indeed any of my early life. I had been nurtured in an insular black school system, where my teachers believed in my intelligence. “You just need to try harder, study more…” I was told by teachers when I did poorly on an arithmetic test or a writing assignment. “I know you can do better than this,” or “I want to see better from you the next time…” I would hear as I received the results of a spelling quiz with bright red Xs beside a couple of words. I was inclined to rise to their expectations. These teachers were in league with my mother.

But in that all-white school, for the first time in my life I faced teachers who doubted my intelligence and my ability to learn. Indeed, in some cases, my white teachers didn’t seem to view me as a human pupil at all. They seemed to see me as more of an inconvenience they had to find a place for on their seating chart so as not to offend the other kids in the class.

My cousin and I arrived on that first day and were stunned to find that, although we were in the same grade and had been assigned all of the same subjects, we did not have a single class together. This arrangement, which even then seemed a deliberate effort on the part of the school administrators to isolate us, was the least of the problems I faced during the two years I attended that school where the junior high and high school were housed on adjoining campuses.

At that school, as I hurried from classroom to classroom, always the one black face in a sea of white faces, teachers and fellow students behaved towards me on the wide spectrum from indifferent to outright hostile. Interestingly enough, I was not once called the “N” word, though I occasionally heard white classmates talking amongst themselves making references to “that black girl” with contempt. I experienced white classmates who refused to sit next to me or work with me on team projects, or who made a big display of turning up their noses and making derogatory faces when some classroom activity forced them to interact with me. From those young white people, I learned much about the cruelty of thoughtless racial prejudice and the social hierarchies and social prejudices they held within their own circles toward other whites.

In my homeroom class there was a white girl who was being raised by her grandmother because she and her younger brother had been abandoned by their parents, which was apparently considered a dark blotch on the girl. She was one of the most honest, earnest people I have ever encountered. But she dressed either matronly in dresses that hung well below the length of the modest miniskirts we all wore at the time, or she wore frilly skirts and blouses that made her look like a first grader. She gazed out on the world through old-fashioned coke-bottle thick glasses, her pale blue eyes wide with the watery innocence of a much younger person, and she wore her blonde hair in a curly permed style from her grandmother’s era. She was in several subject classes with me and I watched her suffer more overt harassment from our classmates than I did. She was often the butt of jokes and simple pranks perpetrated by peers who mostly just ignored me.

One day I saw her eating alone in a deserted part of the school grounds and invited her to join my cousin and I who had early on stopped venturing into the danger zone the school cafeteria represented, where not even a modicum of civility was required of our most prejudiced peers. We brought bag lunches and had staked a claim on a spot behind one of the classroom building where a small meadow with new growth trees gave us just enough sun and shade to eat our lunches and chat in peace.

On another day, my cousin came to our lunch spot trailing a chubby white girl with mousy brown hair and a big friendly smile. She too was often teased and harassed by our peers and relegated to a spot at the bottom of the social pecking order because of her weight.

Our little group was rounded out by a girl who was biracial, native American and black—which meant she was considered black. She had long wavy brown hair, a sweet round face, a regal nose, eyes, angled above high cheek bones and light brown skin that singled her out as non-white. Before joining our little group, she too had spent her lunch hours hiding away from the kids privileged by their uncomplicated whiteness.

The five of us became our own little clique. We gathered not to spend time complaining about our predicaments at the school, but to just be girls. We spent our time talking about typical young teenage girl stuff—the boys we had crushes on, the latest teen heartthrobs in our teeny bopper magazines, popular music, hairstyles, fashion, fingernail polish, makeup (none of our families approved of it), parental/grandparental constraints and occasionally politics.

The chubby white girl even had us all over a couple of times for weekend sleepovers at her house. Her parents were quite gracious to us all, though we later found out they were supporters of George Wallace’s bid to replace President Lyndon Johnson. Wallace was an open and avowed segregationist. Our friend’s parents, and our chubby friend, were quite aware of this. In fact, Wallace’s racist and segregationist policies were partly why they supported him.

This was one of the kinds of sobering paradoxical realities my cousin and I had to navigate. It was a reality where, through intimate contact across color lines, white people came to see our humanity, yet sought to reject or deny that knowledge in the larger contexts of life. It was a confusing and infuriating situation for my cousin and I, and even for our chubby white friend who couldn’t understand why my cousin and I were bothered by the prospect of a U.S. President who wanted America to go back to the separate Jim Crow systems (or worse) of the past.

It was not easy navigating the landscape of teachers either in those two years I attended that white school. I had teachers who exhibited stiff formality with all of their students and didn’t seem to care either way about my skin tone. I had teachers who ignored me, looked right past me in the classroom as if I were made of glass, even when I was trying to ask a question. There were ones who pretended not to notice the white kids who balled up notebook paper and threw it at me while we sat I class. There was one teacher who laughed like one of the pupils when a boy in class imitated me in derogatory ways whenever I spoke. I had teachers who made racial jokes at my expense in front of the whole class. I had other teachers who were publicly belligerent. One teacher looked me straight in the eyes the first time I raised my hand to answer a question in his class and said, “Put your hand down, little colored girl. Are you too dense to realize I’m ignoring you?”

But there were two bright spots among the teachers too. It was my white eighth grade English teacher who first put the idea in my head that I could be a writer. She was young and smartly dressed and seemed a proper Texas belle, always perfectly attired in tailored shirtdresses or silk blouses and tailored linen skirts, modest high heels, expertly styled hair, and well-manicured nails.

Her class had a mix of students, and as usual, I was the only black kid in the room. There were some kids in the class who were indifferent toward me, some who didn’t want to be bothered with me when we were supposed to work together, some who were openly hostile, though never in earshot of the teacher because she demanded politeness in all matters from everyone in the classroom. Students liked her and wanted to be liked by her.

One day when we were studying poetry, she gave us the assignment to write a poem. I toiled and agonized over my poem that was intended to convey something about the way certain classroom slights hurt my feelings. I used metaphors of course, and similes as best I understood them at the time.

On the day she was to hand our graded poems back, she was laudatory of everyone’s efforts, then she said, there was one poem that stood out among the rest. She went on to praise the sincerity of the poem, the cleverness of the author using the techniques we have examined in some of the poems we had studied, etc. Without sharing the name of the writer, she began to read it aloud. I was startled to realize she was reading my poem. My heartrate went up, my armpits and my palms got sweaty, but I trained my eyes on my hands clasped on top of my desk. The teacher’s voice was the only sound in the room. When she finished, she asked the class what they thought of the poem. I ventured a few glances around the room as my peers complimented, puzzled over, questioned and ultimately agreed with our teacher about the merits of the poem. When she finally called me forward to collect my pages with a big red “A” and a collection of exclamation marks scrawled across the top, I walked head down, eyes on the floor, afraid my classmates would retract every good thing they had said about the poem now that they knew the “little colored girl” had written it.

Instead, that day marked a turnaround in my peers’ attitudes toward me. I did not become fast friends with anyone in the class, but the openly belligerent kids, especially the boys, started leaving me alone. They seemed cowed by some new bit of knowledge they had to accept about me. The indifferent kids started treating me with a friendly ease as if I was at least worth the expenditure of energy it took to greet me with a smile or a friendly, “Hey” in the hallway. The ones who had been aggravated when we were required to sit or work together were suddenly solicitous about the genesis of my poetry skills and about English class subjects in general. They started welcoming my participation with class assignments. It was as if they were all seeing me for the first time. For some of them, these attitude and behavior changes toward me carried over into other classes we shared. As I noted, I did not gain any new friendships, but I felt like I had gained something even more important—respect.

I was struck by the fact that writing creatively about my feelings had such an impact on others—my teacher, my peers. There were other elements involved in that moment of realization, but that is a subject for a different essay. Suffice it to say, the reaction to that poem and the positive feedback I received on subsequent creative assignments for that class, set me on a journey to develop what had heretofore only been a love of oral storytelling with my family.

Another teacher in the white school who made the time there livable, and taught some of us important lessons in equality, was my ninth grade English teacher. A new arrival at the school, she breezed in just out of college, her blonde hair cut in a short style that imitated the popular fashion model Twiggy. She wore miniskirts, often shorter than some of the students in the class. She was an egalitarian who insisted we address her by her first name.

At the start of the year, she carefully assessed where each of us was in terms of our reading and writing skills and created individualized goals for each of us, then set us to work in groups not based on the usual social hierarchy, or popularity, or simple academic levels. In fact, it was unclear why she assigned us to the specific groups we were in. There was to be, she told us, no changing of group members and no whining or complaining about our groupmates. “You are all equal members of the group. You are all equally responsible for each other’s success.”

Over time as we worked on the different group projects, helped each other with vocabulary building, and worked our way through the readings she assigned and the group presentations, even I could see we were treating each other with newfound respect and regard. In her classroom, I forgot about my “otherness” compared to the white kids surrounding me. I had the sense they did also. The white girl with the coke-bottle glasses from my lunch group was in that class. Even she seemed to sigh with relief when she walked into the one classroom where she knew no one would tease or make fun of her or make her the victim of a prank.

Of course, when we left our English class period, everyone retreated into their usual groupings. But for that one glorious hour each day, we treated each other like equals focused on the task of learning things we all needed to know.

In 1969 at the end of my ninth grade year, some circumstances in my family changed, and my cousin and I returned to Mississippi to live with my mother and my brothers. My cousin and I were enteringtenth grade, and my mother gave us the option of attending the segregated black high school or the white high school. There were still only a handful of black kids willingly making that daily trek from our side of town to the white high school.

My cousin and I, with the experience of our early years of education in all-black schools contrasted with the experience of sitting in integrated classrooms in a white school (two years for me and three for her), chose to attend the black high school. We had survived our sojourn into the white majority public education world, and we were ready to stop being the shunned outsiders.

It was a welcome return to the embrace of an all-black school. It felt good to see myself reflected in the perfectly attired, knowledgeable teachers at the front of every classroom I entered. I enjoyed the guaranteed visibility of my raised hand and the ready responses to my questions. I liked being pushed to achieve more, do more, be more by black faculty who had no questions about my intelligence or my ability to learn. It was a relief to have all around me black teens like myself in every aspect of campus life.

But unbeknown to my cousin and I, preoccupied as we were with the ins and outs of teen girlhood, a storm was brewing around the future of our education again. The adults in our life were aware of this new storm and were keeping an eye on state and national news about what was to come.

Two of my mother’s brothers had settled in California after individual stints in the military. After a visit home to Mississippi just as my cousin and I started our tenth-grade year at the black high school, they had begun hatching plans to move our whole family out to California when my cousin and I finished high school. They thought life prospects for the whole family would be better in California.

The plan to move us to California after our high school graduation changed when the school desegregation issue in Mississippi heated up in early 1970. Another U.S. court decision regarding separate black and white school systems had led to a new federal government mandate requiring the Mississippi public school system to move beyond voluntary integration, which had been deemed an ineffective way to address the earlier Brown desegregation decision. The new mandate stipulated full integration, and the federal government was forcing the issue. The state and my hometown policy makers began discussing overhauling the school system to accommodate the government mandate. As a result, there was talk of public schools shutting down and teachers going on strike There were protests and threats of violence on both sides of the black-white divide.

What concerned my mother and her brothers was my cousin and I being unable to finish high school. My mother had heard about a community somewhere in the South where black schools were shuttered for five years. My mother was still quite clear about education being tantamount—the magic potion that would help to float us above poverty and the stunted possibilities for most blacks in our hometown. She had developed high hopes that my cousin and I could be the first in our family to go to college. If the schools were shut down in protest, or teachers refused to teach, or were kept from teaching, we would not be able to finish high school. What would happen to us then? What kinds of trouble might we fall into with time on our hands and no prospects for moving forward in life? My mother didn’t even want us to get involved in the active fight for Civil Rights still going on all around us in our hometown and other parts of the South. She had very little faith in a completely positive outcome for that movement.

When the desegregation plans for my hometown were publicized, they did involve closing down the black high school. My mother was not convinced the transfer of all the black high schoolers to the white high school would go well. She decided my cousin and I should go to California and enter eleventh grade in San Francisco. That seemed a clearer pathway for us to graduate high school on time and have a good shot at attending college in California. So, in the summer of 1970, my cousin and I were sent from Mississippi to live with our uncle and his wife and kids to finish our last two years of high school in San Francisco.

When we arrived at the San Francisco high school designated for the district where my uncle’s family lived, our high school transcripts from Mississippi and Texas said we were ready for eleventh grade. But we were given assessment tests anyway. Based on those test results and the subjects we had studied already, we were told we could go directly to twelfth grade. My uncle, suspicious of public school systems and their lackadaisical attitudes about educating black children, advised against skipping a grade. He wanted to be sure we had all the necessary preparation to qualify for entrance into the California higher education system.

For the first time in our educational history, my cousin and I sat in truly integrated classrooms with more balanced mixing of races where our skin tone did not seem to matter in terms of how we were treated. What a relief to sit in an integrated class and not feel as conspicuous as an ink stain on a pristine white shirt. We were surrounded by black, brown and white faces in the student body. The school had black, white and brown teachers in fairly balanced numbers as well. They all seemed vested in the education of all of their students. I felt seen and heard.

But as my cousin and I began our high school journey in San Francisco, back home, our Mississippi hometown’s decision about how to integrate the public schools brought with it massive upheaval in the school system and overt racist violence with many school children caught in the middle. From the safety of my uncle’s home in San Francisco, my cousin and I heard of the ordeals my three school-aged younger brothers and her brother faced attending schools on the white side of town. It was not difficult to imagine what they were experiencing in their classrooms. A year later in the summer of 1971, the rest of our immediate family headed west.

With advice and direction from our senior year guidance counselor (white), my cousin and I did become the first in our family to go to college—my cousin went to the University of California at San Diego, and I went to Northeastern University, for starters. My cousin later went east for a Doctorate, and I swung back west for a Master of Fine Arts.

I cannot say that all of my siblings and cousins have had flawless, prejudice-free experiences in all aspects of the public education system in California. For more of us, however, the forward progress that a solid education opens the door to, has been less fraught with obstacles and barriers.

Paulette Boudreaux, author of Mulberry, won the Lee Smith Novel Prize. She is tenured English faculty at West Valley College in California, and adjunct faculty in the Master of Fine Arts program at the Mississippi University for Women. She has a bachelor’s degree in Journalism from Northeastern University and a Master of Fine Arts degree in English from Mills College.

Sandy Gavin Elementary, 1964-1966, Laurel, Mississippi

Oak Park Junior High, 1966-1967, Laurel, Mississippi

Liberty Junior High, 1967-1968, Liberty, Texas

Liberty High, 1968-1969, Liberty, Texas

Oak Park High, 1969-1970, Laurel, Mississippi

Balboa High, Class of 1972, San Francisco, California

Wow! This essay reminded me of my time growing up in Laurel Mississippi where I also attended Sandy Gavin and Oak Park Elementary school. As I read through the accounts of ill- treatment you all had to endure, I felt like I was staring into a mirror at my own reflection. The feeling of not being seen took it’s toll on my self esteem. Thankfully, I can now see myself and so can others. Thank you for writing this down. There is no way I could have shared this time in my life and know that the listener truly understood how things were. Thanks again.

From your little brother Pernell.

Thank you so much big sister for sharing your Life’s experiences. You helped make my life bearable.

God gave us a mother who believed we could become somebody and pushed us to achieve through self respect and hard work.

I remember the day I said, “I am going to drop out of school early and join the military.” Mom looked me in the eyes and said, ” over my dead body. ” I understand better now, why. Life’s challenges has make us strong and made mom a proud black mother. Education black children in America. Wow! What a wonderful. Thank you for sharing this story of your journey and our families journey.