Dave Tell - Admissions - The Academy Stories Project Scholar

Storytelling is at the very heart of what it means to be human. Indeed, it is a cultural activity so central to the human experience that the inaugural issue of History of the Humanities (2016) declared it a basic human capacity. It enables the fashioning of personal identity, the creation of cultural continuity, and the possibility of political agency. As Cherríe Moraga writes of her Xicana community, “MeXicanas and MeXicanos have always told stories aloud: as weapons against traíciones, as historical accounts and prophetic warnings. . . And through this storytelling one’s awareness of the world and its meanings grows and changes.” Like Moraga, I believe that stories are a cultural mechanism of unmeasured importance for the forging of a more equitable future.

And yet stories also divide us. Many stories remain ignored or silenced. Others are weaponized; deployed to erase histories of difference, of protest, or of lives forged beyond the boundaries of mainstream culture.

If storytelling has always been at the heart of the human experience, the summer of 2020 super-charged the political role of stories and vaulted storytelling to the forefront of the public imagination. Contests over what monuments are allowed to stand in public spaces and controversies over what flags will fly over public buildings are, at the end of the day, symptoms of a fundamental anxiety about what stories get told from the public stage and what histories merit the protection of marble, bronze, or granite.

Indeed, the newfound urgency of public storytelling can be seen with unrivaled clarity in the renewed debates over the meaning of the American past. Consider President Trump’s 1776 Commission, Mississippi Governor Tate Reeve’s Patriotic Education Fund, or the Nikole Hannah Jones’ 1619 Project to which both Trump and Reeves were likely responding. Although Reeves and Jones agree on little else, both are convinced that the future of our republic hinges on what stories get told about the American past.

As I argued on “All Things Considered” in 2019, memorials are the new lunch counters. In the 1960s, people gathered at lunch counters to demand racial progress or defend the status quo. In our current moment, these debates have moved to memorials, our public storytelling venues par excellence. Unlike the 1960s, in which statutes and legal rights were the pressure points over which freedom fighters and segregationists fought, in the twenty-first century stories have displaced legal rights as prize #1 in the fight for social justice.

The so-called “Patriotic Education Fund” is an updated version of pulling Memphis Norman from his stool at the Jackson Woolworths. If the Fund prevails, however, this comparison will not long be relevant. For the violent stories of lunch counters, and the sheer anger of those who sought to reserve the right to sit at them for whites alone, will surely not be told by those who believe that patriotism requires submerging the darker stories of the American past.

The latest threat to the power of storytelling may well be Mississippi Senate Bill 2727, Senator Mike Thompson’s (R-Long Beach) attempt to politicize the Mississippi Department of Archives and History. If passed, the bill would give the power to select MDAH board members to the executive branch of the state government. The preservation and deployment of the state’s stories, and of the Mississippi Civil Rights Museum, would then be subject to the political whims of the executive. Like Reeves and Jones before him, Thompson too understands the power of stories, and S.B. 2727 must be understood as his own, shortsighted attempt to contain that power.

In a culture in which storytelling is contested from across the political spectrum, The Admissions Project is a dear resource. It provides untold stories about race, education, and, at its center, segregation academies. It provides “first-person stories” of southern identity “through the stor[ies] of schools and the promise of education.” Tim Kalich of the Greenwood Commonwealth calls it “a way to document history and also stimulate conversations that might lead to better racial understanding.” It is these things, but it is also more. It is an effort to tell true stories about our past in a moment in which storytelling itself is under siege.

Dave Tell is Professor of Communication Studies at the University of Kansas. He is the author of Confessional Crises and Cultural Politics in Twentieth Century America and Remembering Emmett Till, listed as a 2019 book of the year by the Economist and winner of the Mississippi Historical Society’s 2020 McLemore Prize.

Professor Tell is project scholar for Admissions/The Academy Stories and codirector of the Emmett Till Memory Project. His writing on the Till murder has been published in the New York Times, Chicago Tribune, Atlantic Monthly, LitHub and a wide range of academic journals. He is a past president of the American Society for the History of Rhetoric.

Professor Tell is also Co-Director of the Institute for Digital Research in the Humanities and holds courtesy appointments in American Studies and Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies.

It seems to me that the maintenance of “segregation academies” represents a white war on public education. In many southern towns, you’ll find a segregation academy with 90+% white enrollment and a public school system that’s 90+% black. Where voter suppression and white political muscle help determine public education budgets, one can assume that unenthusiastic support for public schools is race-based. File, I suppose, under “the more things change …” What is the way out of this?

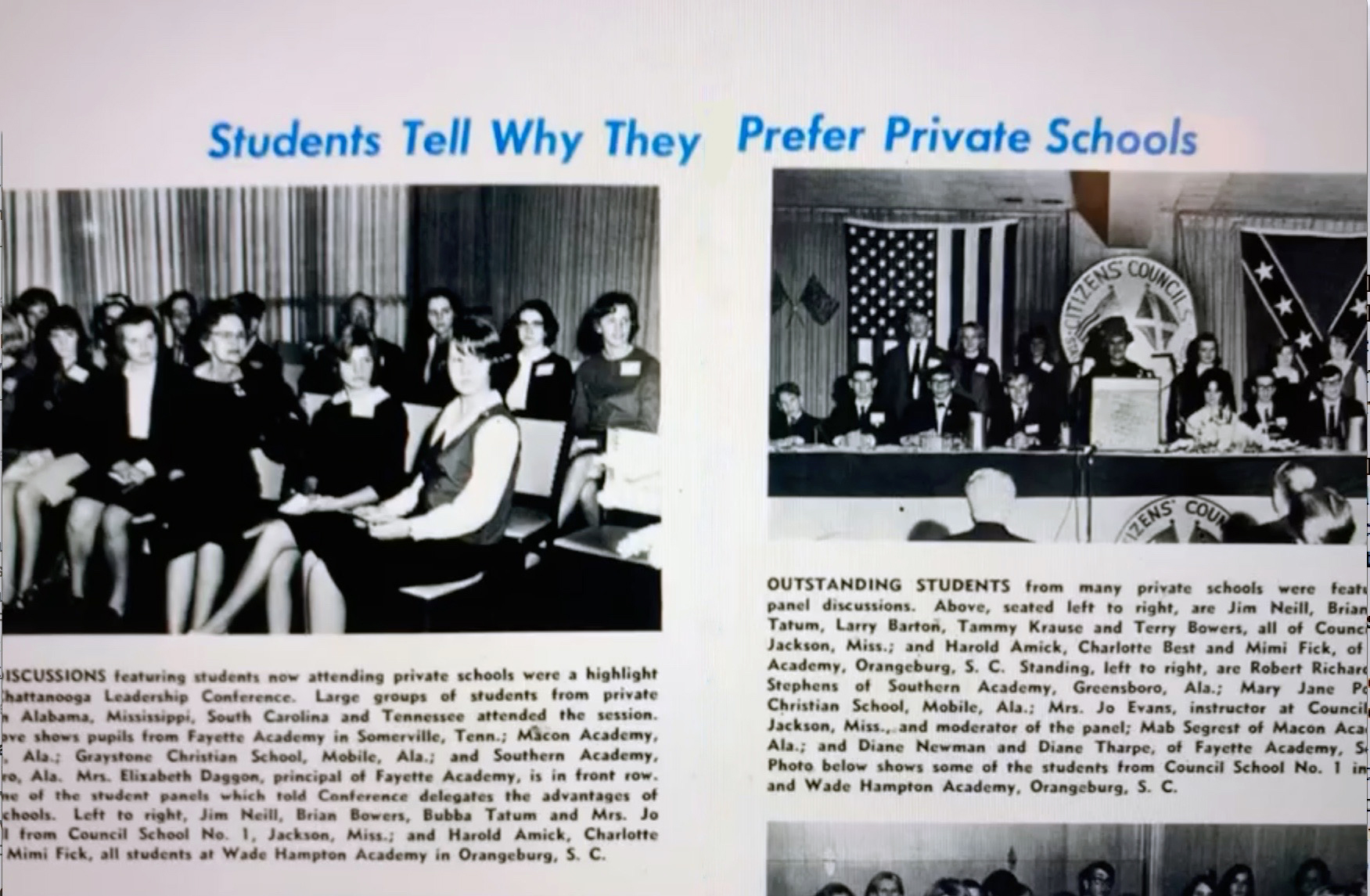

What is the source of this photo?

The Citizen, the old monthly publication of the Citizens’ Council. The issue archive is online through the University of Mississippi library.