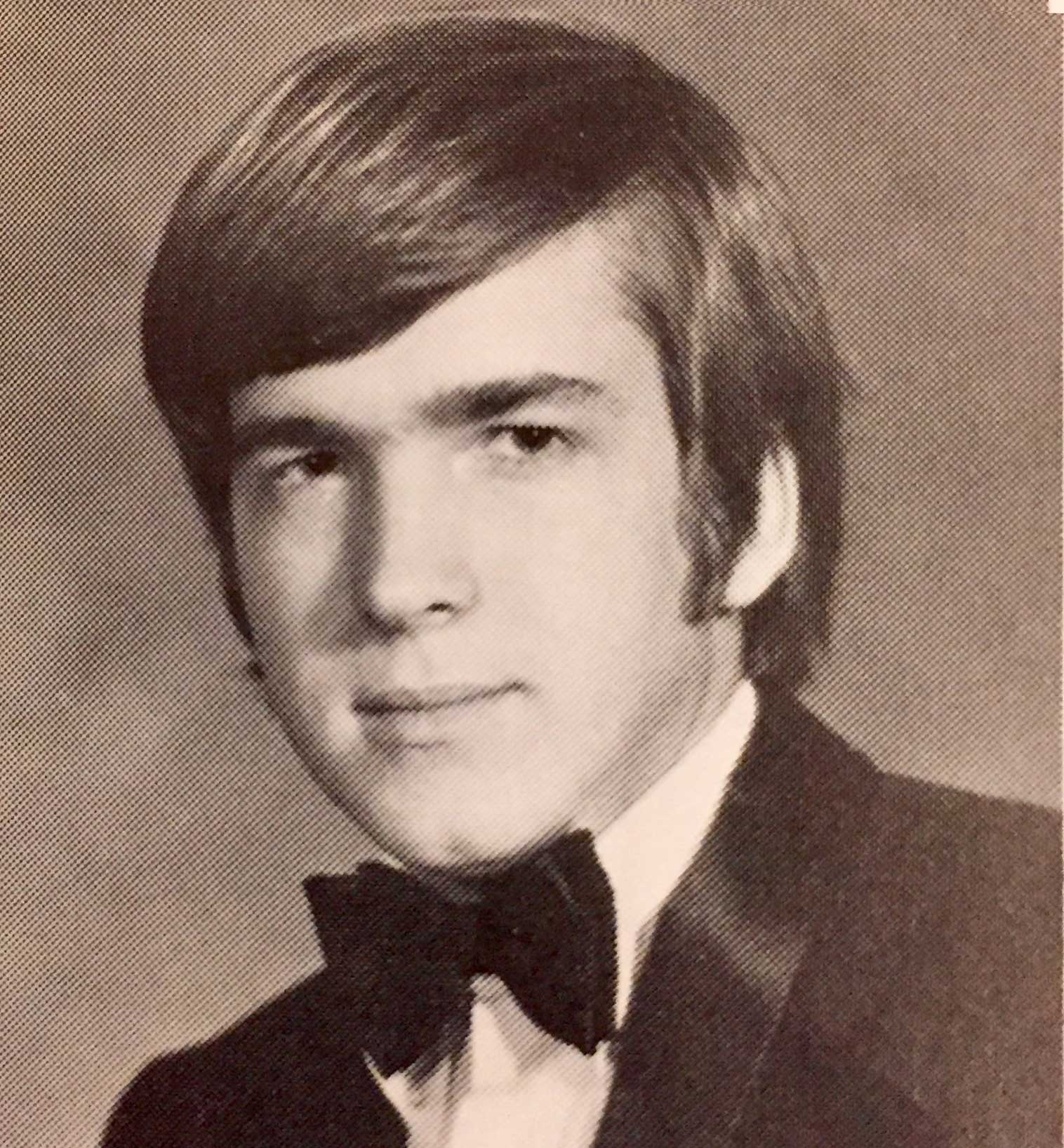

Lloyd Gray Meridian High School Class of 1972 Meridian, Mississippi

When our class entered Meridian High School in the fall of 1969, reaching the summit longed-for since elementary days, none of us had the slightest inkling that we would not be there come January.

MHS was then the largest high school in the state with nearly 2,000 students in grades 10 through 12. Roughly 10 percent were black, it being the fifth year of “Freedom of Choice,” Mississippi’s delaying tactic to forestall full integration. Meanwhile, across town, the all-Black T.J. Harris High School welcomed its returning students.

Fall was flush with the usual high school rituals – pep rallies, football games, homecoming parades, class elections, privately sponsored dances that had replaced pre-integration school-sanctioned ones. We tenth graders spent the fall assimilating, finding our place and securing our identity as high school students. We had finally arrived.

Then events upended our world.

I was not prepared to be told I had to leave Meridian High. I had just gotten there, for heaven’s sake. It wasn’t fair, I thought, the fairness in my mind purely personal and devoid of any historical perspective.

When the U.S. Supreme Court that fall ordered an immediate end to dual school systems in many Mississippi districts, including ours, Meridian responded by directing all tenth graders – Meridian High and Harris High students both – to attend Harris after the Christmas break. Meridian High would become the school for all eleventh and twelfth graders. Harris would now be known as Meridian High School/Harris Campus and would house tenth grade only.

Half the white tenth graders who had entered Meridian High that fall from the city’s two almost-all white junior high schools had never gone to school with a single Black student before setting foot on the MHS campus. Now we were heading to the formerly all-Black high school. Or at least most of us were.

In my social circle, we quickly inventoried each other’s and our parents’ wishes. We wanted to stay together, upset as we were about leaving MHS. But it would be only one semester, and then we would be back where in our minds we belonged. Our parents, business and professional people for the most part, were willing to let us go.

But there were a couple of girls in our group who were struggling with their parents for whom massive integration was bad enough but sending their daughters to the Black high school in a Black neighborhood? It struck at the core of their racial phobia. Yet the girls persisted and their parents relented. It had little to do with doing the right thing; they, like the rest of us, just didn’t want to leave their friends.

Yet other parents insisted, and they were able to do so because there were ready-made white flight options available, Jeff Davis Academy and Lamar School, both of which had been around and harboring the elementary-age children of hard-liners for several years since the first Black student crossed the threshold of a formerly all-white school in Mississippi. Any integration apparently was too much integration for the founders of those schools, who nevertheless insisted that it was a desire for “quality education” that gave them birth.

A few of us, once the reality of the impending move sank in, began to consider it our duty to hold our class together. We pleaded with and cajoled those outside our circle.

The whole community wondered what the schools would look like come January: Would most of the whites come back, or would there be wholesale desertion? What would this mean for our schools? For the future of our community?

Whether you supported the public schools or whether you planned to duck and run to a segregation academy became a sort of litmus test for many in the white community about not only your educational preferences but your worldview. The choice was clear: Stay or flee.

As it turned out, a few dozen of our classmates outside our circle left, blue-collar families for Jeff Davis mostly and the upper middle class and wealthy for Lamar. Even segregation academies tended toward class distinctions.

But the departures weren’t anywhere near the scale of other places – the Delta, other Black majority counties, even Jackson – and the Meridian whites who held on were able to pat themselves on the back for having come through the crucible with the public school system largely intact as the educational choice for most segments of the community. We had passed the test, in spite of the best efforts of the private school advocates.

Over the years, unfortunately, that success gradually eroded. When I graduated from Meridian High School in 1972, the system was about 60 percent white, 40 percent Black. When I returned to Meridian in 1990 as editor of its newspaper, the district was 65 percent Black. Some of it was white movement out of the city into the county, but much of it had to do with the presence of Lamar, the principal private school survivor of the desegregation era, and its steady progress in luring the white business and professional families and their pocketbook support away from the public schools.

Twenty-three years after leaving Meridian for the second time I returned again in 2015 to live and work, and found a district more than 90 percent Black and mostly poor. The children and grandchildren of numerous prominent Black business and professional leaders were now enrolled at Lamar. Few give much thought today to the school’s origins, nor to its role in diminishing support for the public schools at the expense of the predominantly low-income Black children who now attend them, not to mention the ability of the community to sell itself to the outside world.

Lamar School is not the school it was in 1965 or 1970. It is a better, more diverse and more educationally well-rounded place. But the question remains: How would Meridian have been different if it had never existed? What might the community, given no place to opt out, have looked like – economically, educationally, socially – if everyone had stayed with the public schools that were universally embraced prior to integration?

We’ll never know the answer, but it’s a pertinent and penetrating question all the same.

Lloyd Gray was a Mississippi journalist and newspaper editor for more than four decades in Greenville, Biloxi, Jackson, Meridian and Tupelo. He now works in education philanthropy and lives in Meridian. His wife, Sally Gray serves on the Meridian Public School District Board of Trustees.

To the best of my knowledge, nobody has ever asked people who attended once-well-integrated schools why they left. These were people who were okay with the idea of integration, but then they weren’t. People don’t want to be pinned down on this, but these people didn’t leave because of skin pigmentation. Why did they leave?