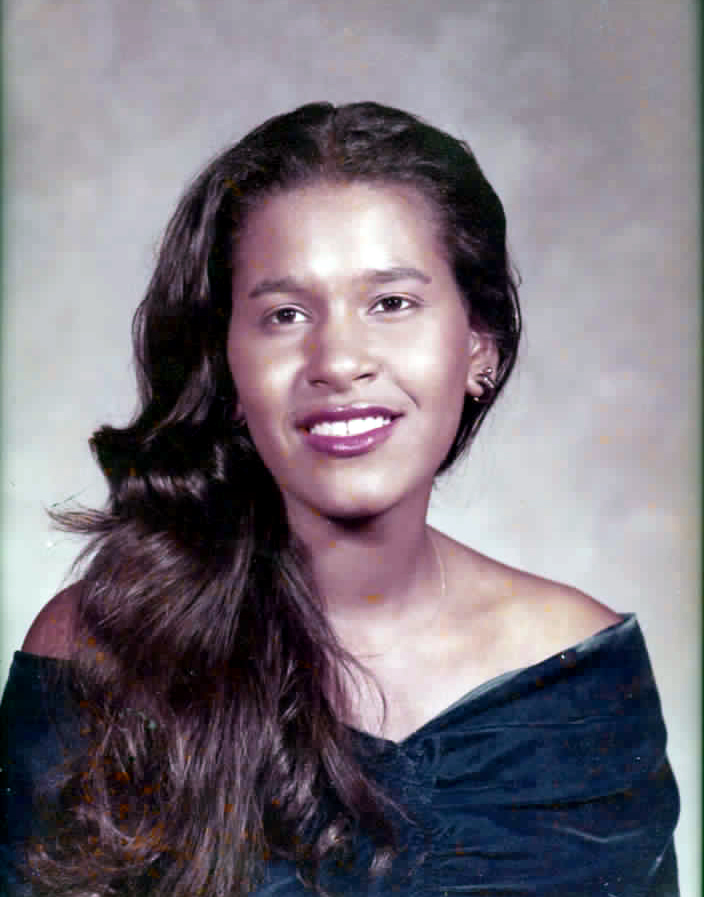

Selika Sweet - Murrah High School - Class of 1979

I was 14 years old in 1976. It was the national Bicentennial year, heavy on firework shows, programs and red, white and blue packaging on store shelves, all celebrating the promises of the 1776 Declaration of Independence. There was promise in the air locally too, with another chapter of American history unfolding as Jackson settled into integrated public schools. It had been six years since federal courts ordered the system to integrate in 1970.

After growing up in Catholic schools in Jackson, I decided to enter Murrah High School for tenth grade. Murrah had been the historic flagship public white high school before integration and even its location seemed to signal significance to me: across the street from University of Mississippi Medical Center and the G.V. (Sonny) Montgomery VA Medical Center. Looking back, maybe that was a tip off to my future, or maybe it was the fact that my father had previously worked at the VA facility. He’d been in the medical lab as the center’s first Black professional hire. To me, Murrah High School had felt like the nexus for a lot going on in Jackson. I thought the switch to public school at Murrah would broaden my horizons. I’d meet more people and experience a wider world.

But integrated wasn’t the same as transformed, I was going to learn. Inside the school, a sense of segregation remained. I was surprised at how much hostility the Murrah system held, sometimes in overt moves, other times in missed opportunities to make Black students feel incorporated. In my three years at Murrah, I have to say the worst of my experiences were with white faculty and staff.

I tried out and was selected for the Murrah Singers, the school’s long-running prestigious choir. On our very first day, the very first song the director had us sing was Dixie. I was shocked as I heard my fellow choir members—the choir was probably forty percent Black— sing. I kept my mouth closed as the others made it through the lines that made me cringe. After class, I asked if I could talk to the director. I told her I didn’t feel comfortable singing Dixie. “You don’t tell me what to sing,” she said. “You are no longer in the choir.” Before I could say another word, I was out. For the rest of the year, whenever I questioned my treatment by adults at the school, I wondered what impact that choir moment on the first day had had. I had the feeling word had spread.

I’d have to say there typically wasn’t hostility on the part of white Murrah students. Many of the white students came from Jackson households with education and wider horizons. After all, they had chosen to stay at Murrah while so many other whites had fled to the new all-white segregated academies when integration began. Yet that’s not to say there weren’t limits with my classmates. Yes, I was a Murrah Miss, a member of the high school’s famous drill team. I drove lots of girls to our practices and after parties because I was a lucky one with a car: a 1974 blue Dodge Dart. A sense of inclusion only went so far, however. People are often lonelier than we realize. Despite participating in Murrah activities, I didn’t make close friends there. Meanwhile, my childhood friends Sonya and Catherine both attended Callaway High School, and we lost touch in a sense. The busy Murrah hallways may have looked integrated at first glance, but I felt like a loner.

Here’s another example of how my Murrah experience looked inclusive yet kept missing the mark. In 1977, our advanced history class took a day-long field trip to New Orleans to see the King Tut exhibit at the New Orleans Museum of Art—a huge event that year— and walk around the French Quarter. It was a nice idea. I was the only Black student on the trip, and I felt nothing short of isolated. Boarding the bus, I noticed one white classmate who seemed as sidelined as I was. She was sitting by herself, so we sat together. My memory is that she had long brown hair and seemed very nice.

It was supposed to be a thrilling day. Yet as the bus moved past the Mississippi pine trees and southward through the Louisiana swamps, I kept thinking about how shut out and isolated I felt. I questioned why had I chosen to go to Murrah. I’d wanted to meet more people, and I had. That was true. Yet the connections were surface deep. It was the same with my lonely white seatmate on the field trip. We bonded for the day. I dropped her off at her house in my Dodge Dart when we returned to Jackson that night. I’d never noticed her particularly before, nor did our connection last. It had been based on how each of us needed a seatmate for the class trip.

This brings me to Murrah’s most blatant systemic segregation in my years there: access to advanced classes, math and history in particular. There was tracking by race, it seemed clear. If a student was in an advanced section of a course, the work was great and challenging. Be pigeonholed as average, and there you stayed in a regular class. There were very few Black students admitted to accelerated math and history.

I was in an honors American history class at Murrah with one other Black student and approximately 28 white students. Looking back, one of the most pivotal moments in my life happened in that class, actually. The topic was American history. In retrospect I was living American history in the class too. We were discussing the U.S. Supreme Court case of Allan Bakke, a white applicant rejected for medical school in California. Bakke sued to dispute the medical school’s affirmative action quota, which reserved 16 of its one hundred slots for Black applicants. I knew about the case because in visiting my older brother and sister in law school in Washington, D.C. at the time, I’d heard talk about it.

The history teacher concurred with Bakke’s argument of reverse discrimination for whites. I had to say something. I didn’t think I was being disrespectful, just presenting the other side of the question. “There’s a need for affirmative action,” I said. “Look at Murrah. Look at how few Black advanced placement students there are.”

I can’t say she outwardly lashed back at me. She did that silent shutdown that’s a classic long-standing white reaction to being questioned on racial beliefs. Her fury was in her stiff defensive body language. She didn’t want a debate. She wanted her side to be the end of the discussion. I was surprised and disappointed at the way she halted the conversation. In my previous years in Jackson’s Catholic schools, the atmosphere always welcomed civil conversations that aired both sides of a debate, including on abortion, capitol punishment and euthanasia.

I never felt a drop of warmth from that history teacher for the rest of the year. I wasn’t surprised later in the term when she told our class that our advanced section was the only one of her sections that she bothered to teach. The message was clear: her other history sections were regular history, where nearly all the Black students were assigned. She didn’t think teaching those sections rated any effort. Also during that year, she defended herself in calling out a Black male student in another section on misbehavior. Word of the incident had gone around school. The student was being disciplined, but some questioned if he was guilty or not. “Well, if he didn’t do that, he did something else. He had punishment coming anyway,” she said—or along those lines.

That white history teacher’s hostility had an ironic fallout in my case. It convinced me I wanted to go medical school as did Bakke. I wanted to be in a field where data and science drove reality. I decided my future was in science, where someone’s subjective feelings about you were less likely to determine your fate. Science was quantitative. I thought it was the best path to side step people like her, with fuzzy abstract illusions that she could insist were truth.

That moment led me to choose medicine as my field. Ironically I would be applying to medical school, just as that teacher’s white poster boy Bakke had done. His case against affirmative action resonated with her, yet she was blind to the white affirmative action in front of her in our own nearly all-white class.

Selika Maria Sweet, M.D. is a family physician and a writer. Her work has been published by The Bitter Southerner and Kings River Life. She is a seventh generation Mississippian. She enjoys researching and writing about regional history and is writing a history of the Flint-Goodridge Hospital in New Orleans.

Awesome piece Selika!!!!!!!

I remember well.

James L. Henley, Jr., Esq., CPA/CFF

Excellence…

Always!

Indeed, quite an interesting read re: your high school years at Murrah High school. l am sure this experience prepared you as you persevered throughout medical school, and in the working world! My Blessings.(BRJ)…BJean R-J

Great read. Excellent.

As a 70 year old white woman who graduated high school in Waynesboro, MS in 1970, and having lived in Atlanta for almost 40 years, I love your story! I hope you went back to Murrah and presented your M.D. to that history teacher when you finished medical school!

Dr. Sweet, thank you for this. I graduated from MHS in 1972 and my brother in 1974–we are white. I appreciate your honesty and grieve at the blindness of the white teachers you clashed with there. You were brave and right to speak out, and their reactions speak volumes about how they weren’t prepared for the changes that came beginning in February of 1970.