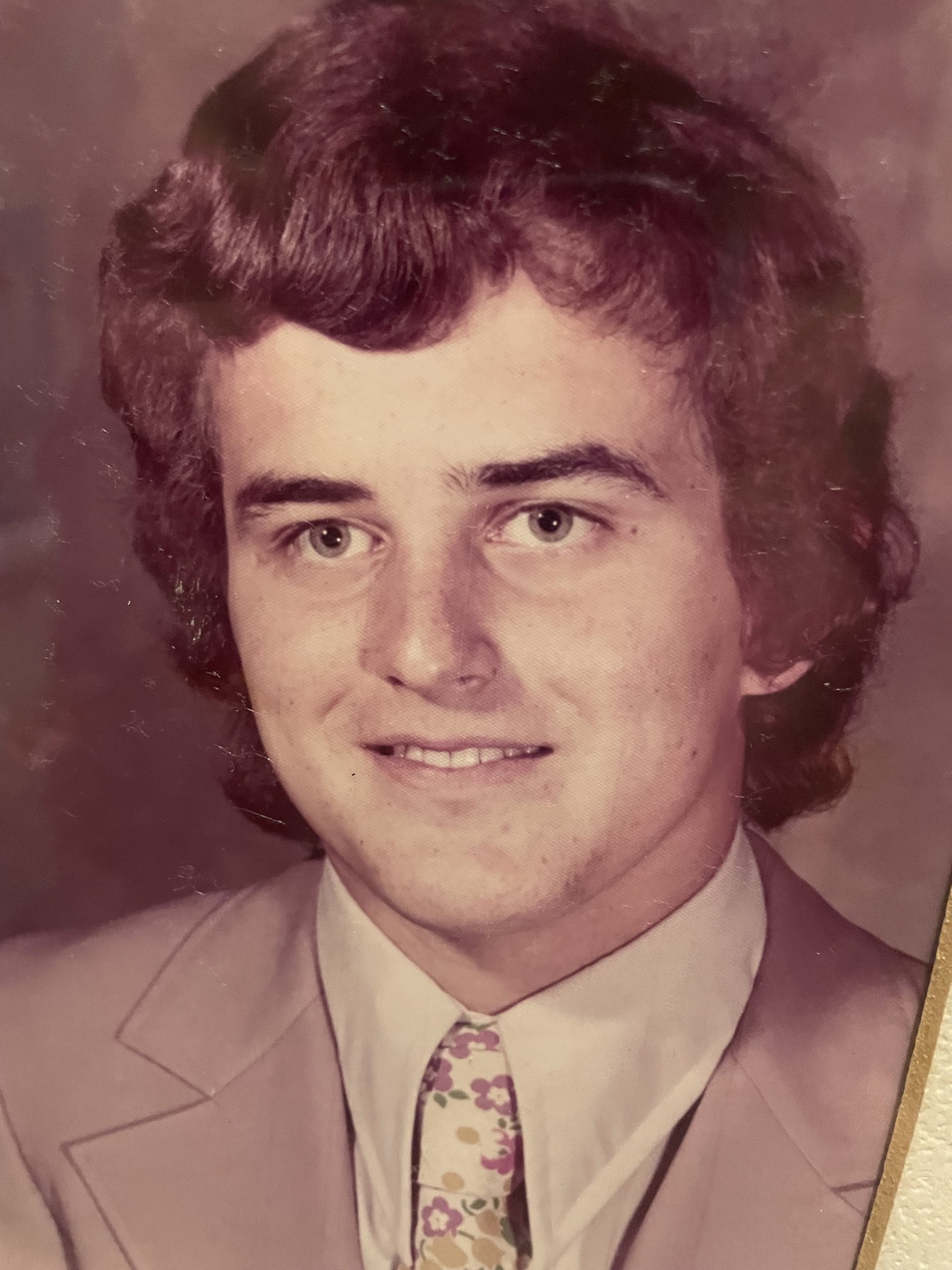

Timothy J. Alford –Greenwood High School–Class of 1974 -Greenwood, Mississippi

The Yazoo River splits Greenwood, Mississippi into North and South Greenwood. That’s more than a geographic fact. It turned out to be demographic destiny too. Those of us who grew up on the Southside as children had tree swings that arched above the Yazoo’s turbulence. We fished for gar and catfish. My brother hopped a log in the winter floodwaters and was almost carried off until he swam back in the icy Yazoo to the bank. My father built a 30-foot sailboat, floated it down the Yazoo into the Mississippi near Vicksburg and ultimately moored it in Ocean Springs.

The Yazoo is an Indian word for tadpole place, and it indeed brought life to Greenwood. It was a major highway for barging cotton during the King Cotton days and provided the town’s economic vitality, even though its waters were pocked with whirlpools. It was supposed to be off limits to us Southside kids. The Yazoo River looms large to me because it was the defining barrier between the more affluent white families on the north side of town and those of us on the Southside. Indeed, the majority of the white kids who remained at Greenwood High School after mass integration in 1970 were from the south with few exceptions.

My father, John M. Alford, grew up in south Louisiana. My mother, Virginia Small, three miles outside of Greenwood. They found each other at Charity Hospital in New Orleans. My mother was doing her dietitian internship, and my father an internship in Medicine.

How my parents arrived on the same side of racial moderation as they returned to Greenwood in the late 1940s to raise four children in the heart of the Mississippi Delta is a mystery. I know that my mother took her religion seriously. As a teenager, she memorized every verse of every song in the Methodist hymnal!

In the fall of 1966, our town’s white-flight academy opened. That same autumn, my mother spoke up in a letter to the Greenwood Commonwealth, lampooning the city leadership for egging on white harassment of two Black teenagers who bought movie tickets to the Leflore Theater. “Fear was riding where courage had walked while conscience leaned and stood and considered,” she wrote in the piece she titled “A Bad Conscience or Something I Ate.”

This got my parents in more than a little trouble with the Citizens Council. The phone would ring at night. When Dad answered, there was nothing on the other end except breathing —not heavy breathing, just breathing. This was physically and emotionally exhausting for my father who, before the era of emergency room doctors, answered lots of late night calls. True to small-town irony, the head of the Citizens’ Council was a patient of his. Dad appealed to him, and the phone calls stopped.

As the city schools prepared for full integration, I attended a tense adult meeting at the courthouse when I was junior high age. Byron De La Beckwith, eventually convicted of civil-rights leader Medgar Evers’ murder, shouted with a red face about the federal courts’ upcoming enforcement of the Brown ruling. An adult attendee of the meeting later told me the typical Greenwood segregationist believed that mixing the races was not Biblical and that it violated the traditional culture.

Yet other whites hoped to do their part to make the change happen as smoothly as possible. Hollis Rutter, longtime football coach at Greenwood High School and Mississippi College, rose at the meeting. “I can teach anyone to play football!” His words were not only profound but also prophetic. In 1973, Greenwood would play for the Big 8 State Championship against Vicksburg. Coach Rutter also taught American Government and was passionate about it. He was a student of Franklin Roosevelt. If I heard him say FDR in class once I heard him say it a thousand times! Coach Rutter was a fan of the common man.

I am sure my parents had hard discussions about whether our family, too, would leave the public schools for Pillow Academy, but they made their decision and stuck by it. My brother Peter and I would stay in the public schools. Our two older siblings John and Helen had already left for college.

Here’s what hurt: Friendships were just snuffed out. A wall went up. While most of my white friends left for Pillow Academy, our family became relatively shut off from long-time friends. I was no longer invited to gatherings of the Pillow students. We had lost friends and thought we were not equipped emotionally to deal with the engagement of new friendships.

Yet in spite of myself, I was starting to form relationships in a new culture within my old geography. Band proved to be the key. Music heals. Our new Greenwood High band director Donald Anthony was one of the best teachers I ever had. He sat first chair trombone at the University of Mississippi for four years and held a high standard of excellence. He taught a class of twelve of us college-level music theory. His lessons have stayed with me to this day. Very quickly, Greenwood became one of the state’s finest marching bands. Our 50-50 racial mix was a showcase when we marched in downtown Greenwood parades.

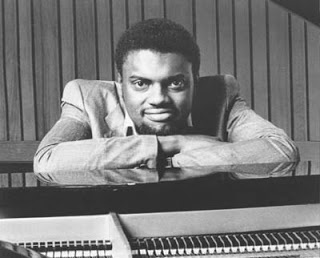

Two of my new African American classmates had a huge impact on me: Ezelle Wade and Mulgrew Miller. We three entered the band as 15-year-old freshmen. Mulgrew played tuba, I played trumpet and Ezelle was a percussionist.

Our sophomore year Mr. Anthony had new band uniforms designed that were almost identical to Ole Miss’s band. He also managed to get us an invitation to play the pre-game show for an Oxford home game. At a particular melodramatic point in the show, Ezelle Wade who possibly weighed 70 pounds and looked like a perfectly formed toy soldier, walked forward. The band stopped. Ezelle, with theatrical flair, punctured the silence with an enormous cymbal crash with flawless comic timing. It brought the Vaught Hemingway house down.

By his final two years at Greenwood High, Ezelle was on his way to becoming one of the most talented and serious snare drummers I ever knew. He was accepted into the prestigious Lions Band and could play traps for anyone.

Integration in Greenwood came with a drawback that happened in so many towns. Experienced Black educators, arriving in previously white schools, found themselves new subordinates. That was the case of Mr. Nathan Jackson, former head band director at Threadgill High School (the all Black high school across town). Mr. Jackson brought his own talents to the Greenwood High School Band, including humor, great timing, humility and musicianship. He was a heck of a saxophone player and had his own jazz combo that played around the state. He and Donald Anthony made a great team.

Mr. Jackson knew something that was going to change the course of our high school experience. In other words, he understood what Greenwood High had in Mulgrew Miller. Mulgrew Miller would become one of the finest jazz pianists in the world before too many years.

Back then, most of us first came to understand Mulgrew’s talent as we first heard him play Caravan. He had drawn a crowd to the upright piano in the band hall. As Mulgrew moved through the Duke Ellington song, we were all transfixed. His music sparkled with clarity and deep emotion.

He could also be a bit of a cut-up. I sat behind him in the trumpet section, lucky to get to become his friend. Whenever someone was playing a good musical line, Mulgrew would do his famous finger pointing, nose wrinkling snark face. Mulgrew could even snark himself by playing with one hand and finger snarking with the other.

It was poetic that that very first song I remember from Mulgrew was Caravan: he helped transport any racial preoccupation away. He was the kindest, sweetest, most talented young man you could ever want to meet and had single-handedly put our stage orchestra on the map. He made us all better people and musicians.

His extraordinary talent was a balm for our own prejudice. He was a dear friend, to be sure, but when he sat down on the piano bench he was of another world. His playing was transcendent. He made us realize that our own anxiety about the new school normal was ridiculous. What was it that we should fear? Admittedly, not every public school had a Mulgrew Miller, but for us, Mulgrew generated such wonder and power that all blind prejudice was eclipsed. Why were we so lucky to have known such a genuine human and genuine genius? The only answer I have is that it was simply a gift.

Mulgrew went to University of Memphis on a full music scholarship. He went on to be principal pianist with the Duke Ellington orchestra. He occasionally played with fellow jazz great and Mississippi native Cassandra Wilson, who coincidentally attended Murrah High School in Jackson with my future wife, Mary Al.

Mulgrew’s last return to Greenwood was for a memorial concert for Nathan Jackson, who’d done so much to nurture Mulgrew and the rest of us at that pivotal time. Mr. Jackson, sadly, died of a heart attack at only age 54 in 1990. After the concert, a few of us had gathered in North Greenwood on a porch facing south. Mulgrew remarked that so many in our Greenwood High class had gone on to have professional music careers. He was proud of that association. Lee Lee Carroll had become principal clarinetist for the Nashville Symphony. Mary Wooten’s career as a New York cellist included playing at Lincoln Center, on National Public Radio and in New York’s other major halls. She has played back-up on stage for David Bowie, Madonna, Aretha Franklin and more. Debra Floyd kept her talents closer to home as a church organist, pianist, vocal leader and, recently, helped us keep our spirits up with wonderful Zoom musical gatherings during the pandemic.

As we looked south across the Yazoo River, Mulgrew told us that he had played in over 45 countries and yet standing in North Greenwood still made him anxious. We talked into the night about the feckless response of so many whites to the federal courts’ mandate. This was the original sin from which Greenwood would never recover. This court order from the deep well of our Constitution re-affirming that we were all created equal was given an end run in the 1970s. As we looked at the treacherous Yazoo River, the view embodied what had happened to our town: two banks, two sides and a channel that cut very deep. The Yazoo flows ever to the sea. Its timeless presence divides, but not any more than we divide ourselves.

Mulgrew died too early at age 57 at his home in Allentown, Pennsylvania in 2013 from a hypertensive stroke. If only our white classmates who left for the academy could have known Mulgrew. He turned our white group’s pathologic cultural bias on its head through his friendship, good humor and music. He left his friends with a profound appreciation for those of a different race.

I remember that Mulgrew loved Duke Ellington’s Come Sunday and played it at Nathan Jackson’s memorial concert. The first verse to Come Sunday is:

“Lord, Dear Lord I have loved, God almighty, God of Love, please look down and see my people through.” Mulgrew did that. He saw us through.

It’s probably no coincidence that when my future wife, Mary Al and I met at Millsaps College, we had the shared bond of the experience of attending public school while so many of our white childhood classmates had fled for academies. In fact, we eventually chose to live in Kosciusko, Mississippi because the city leaders consciously made the decision to hold public schools intact during desegregation. Kosciusko schools have remained strong and vibrant although vastly underfunded. Our own three children are graduates and have a deep appreciation for diversity within their own lives.

Dr. Timothy J. Alford practiced Family Medicine in Kosciusko, Mississippi for 32 years. He is a former president of the Mississippi State Medical Association and the Mississippi Academy of Family Physicians. He is a graduate of Millsaps College and the University of Mississippi Medical School. In Kosciusko, he worked as president of the PTA, Habitat for Humanity and Kosciusko Foundation for Excellence in Education.

Thank you for this powerful testimony. I have learned and grown just by reading it.

I was privileged to know Mulgrew as a member of the GHS band. And Tim is right, he gave us the gift of music that crossed the racial barriers that so many had tried to put up to keep us apart. I’m so thankful that I was a part of that culture in the band.

What a powerful reflection What a great family!

Nice, Tim. You have a great memory.

So I saw Mulgrew last, about a year before he died, not only playing at the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival with a tribute to Duke Ellington, but being interviewed so other musicians could learn from him. We spoke before the interview. I don’t believe I had ever seen such God given talent, fame, yet such humility in any one person. He remembered me well, and was sad I had not pursued music beyond college. Yet, he still pointed to me in the audience, and called me by name during the interview saying I was one of the best saxophone players he had known and we played together in Greenwood, MS. I was extremely embarrassed as I was surrounded by professionals.

But in hindsight, his doing so, he let me know again, that Mulgrew had remained the same great, humble, encouraging guy that I had known in the GHS Jazz/Stage band.

And what a band we had!

This is an awesome testimony and recollection of events! I was a member of Greenwood High School band during the time. I thank you for the accolades given to Mulgrew, Ezelle and Mr. Jackson. I applaud the decision your family made regarding integration.

Cheryl Wilson

GHS class of 1975

Trumpet

I graduated from Threadgill High School in 1967 and worshiped at Decell Methodist Church with Mulgrew Miller’s family. While vacationing from Minnesota, I attended Decell on a Sunday that Mulgrew was present. I sang a hymn, “Because He Lives” and Mulgrew played the piano. When I look back, I did not know that I was with one of the world’s greatest pianist. What a blessing. I am proud to be from Greenwood.

This is a wonderful article. His dad was our family doctor. Wonderful family

This is a wonderful Tribute or life memory that was told with so much honesty. I lived reading it. Mulgrew was my classmate. He was so musically inclined. You could always find him hanging out at the Band Hall with Mr. Jackson.

My sister, Janice Cain, was the first colorful Majorette at GHS. She had lots of good friends who were in the Band also.

D.A. meaning Don Anthony, was a household name in our house.

My sister and her friends seem to have enjoyed their time in the Band at Greenwood High School.

Thanks for the memories Tim.

What a beautifully written, thoughtful tribute to what constitutes the best about the family of man in a trying time and in a most trying place. Timothy Alford’s vision about a painful chapter from Mississippi’s past is not only restorative but fills me with hope.

Beautiful. God bless.

What a beautiful memory. Brings back lots of memories. Thank you for sharing.

Beautiful remembrance. I knew Mulgrew in ‘70s Memphis and he was always so kind when I ran into him in later years. What astounding talent.

Thanks

Nice piece Dr. Tim, nice piece.

Hi Dr. Tim. I’m Mulgrew’s baby sister, Arletta. Thank you for the memories of Mulgrew and his band classmates. Believe it or not, I remember your name mentioned quite often. I was only 9 years old when Mulgrew graduated from high school. I use to listen to the albums that the concert band made. They were superb. I wish that I had copies of them now. It’s amazing how a high school band could sound so great.

I enjoyed the article. Thanks for sharing. Mulgrew was my neighbor and your father was my doctor.

I enjoyed reading this so much. I grew up in Greenwood and graduated from Greenwood High School in 1991, my mother in 1973. I believe my experiences and the relationships I formed there have impacted my life in so many positive ways. I’d love to hear more of your experiences. Thank you.

Thank you for sharing your excellent piece. I was born in Greenwood, and graduated from GHS in 1966. Your brother John was first chair baritone when I became a member of the GHS band in 1962 (I also played baritone).

I believe that the dominant factor in the demise of Greenwood was the fact that I-55 bypassed Greenwood. However, I have always felt that the flight by whites to Pillow Academy had a good bit to do with end of the growth era in Greenwood because support for the public school system became weak. Greenwood was bustling when I lived there. Now, downtown Greenwood is pretty much a ghost of what it was back then.

I strongly believe that if a person is elected to public office, they should be required to send their children to public school.

Thank you for this beautifully written piece, Tim. Your mother is beaming with pride out there. Love to you and your dear family! —Lee Lee

Beautifully written Tim. Your article brought back many fond memories. Thank you for sharing.

Great memories growing up in Greenwood, enjoyed the article!

Elaine Tucker Black

This was such a wonderful description of life in Greenwood in the mid-60s and 70s. I grew up in Grenada and came to Greenwood often. I didn’t know Mulgrew Miller, but I feel like I know him now. What an inspiring tribute to him and to others who had the blessing of knowing him in his youth!

Thank you for this wonderful piece Tim. As Lee Lee said, ” Your mom is so proud of you and smiling down.”

Thank you.

What a heartfelt memory! I graduated from GHS in ‘67, with Helen Alford. That was the first year of integration. These private school vs public school dramas are still being played out today. I think high school students are naturally clickish and stick with their own high school. Some school policies even exclude others from proms and other functions. Thank you for sharing these memories of your talented friend and the way he made a difference. That is so inspiring!

I am so thankful Serena Lusk Coleman shared this with me. My memories of those times in Greenwood MS are intertwined with yours. And what with the world’s condition today and in not aiming to downplay those tough times in the 70’s we experienced, nonethless, your tribute has added a halcyon glow to my memories… Thank you.

.

A cymbal solo! Yes! First and only I’ve ever witnessed! And it was perfect!

I most def agree with Lee Lee how proud this would have made your mother – and I want to add Granny Small, as well. They were two of the finest women I have ever known. You’ve accomplished so much to be proud of, Tim. I am proud to have known you, Mulgrew, and so many more from Greenwood, MS.

Fantastic tribute to a dear friend and courageous families. Thank you for sharing!