Catherine Bigger, Ph.D. –Magnolia Academy–Class of 1983 -Jackson, Mississippi

The culminating moment from my twelve years of schooling at white Citizens’ Council School Number 6 (later Magnolia Academy) actually occurred post-graduation in my first class of my first year at Hinds Junior College. I entered the classroom, sat down in the front and along came a Black male student who plopped down in the seat next to me. It was the first time in my life to share a class with a Black person. I don’t know how long I stared at him, but he never seemed to notice. It was a physically dizzying experience with multiple thoughts flooding my mind, “There isn’t anything imminently threatening or mysterious here; he’s just here to learn as I am.” “What is the big deal?” “What was the point of all those academy years shunning contact with anyone Black?” Of course, for me, the answer was there had been no point at all to the academy.

I mustered the intestinal fortitude to declare as much to my grandmother on a visit home after I transferred to Mississippi State University. I’d formed one of my first friendships with a Black student. This aspiring veterinarian had an old, faded-yellow car that I can’t remember make and model – the kind of car most of us drive when it’s our first car that runs mostly on prayers and swearing. His car clearly had seen better days, but it moved, and he would let me ride with him back to Jackson, never once letting me help pay for gas. Once after dropping me off at my grandmother’s house, instead of seeing him as a generous friend, she only saw me in the car with a Black man and was upset. She followed me through her house and huffed, “You’re going to get a reputation!” She hadn’t sat next to the Black student in my first college class or listened to my friend express his dreams on the two and a half hour-ish trip to Jackson from Starkville. As respectfully as I could, and as difficult as it was to openly defy my grandmother, I drew a deep breath while turning to face her and simply said, “Good.” Honestly, in that moment, that single word response was for both of us. I too was a product of my environment, and everything I’d learned or been exposed to at that point that now collided with my college experience. I delivered that word “Good” to her and to myself as an affirmation of change.

After those first few days in college, there was nothing remarkable to me about attending school with Black students. When it rained, we all got wet; tests were tests. Even now, I hear and read Facebook posts by my fellow academy alumni in 2021 (sadly some of them are teachers now in Mississippi) arguing that our academy was necessary because Black students were not as academically prepared as white students, or that the all-white academies were an effort to maintain higher standards that our parents feared would be lost by desegregation. Rationally, if that were true, then why were those of us coming from supposedly superior academies now in college classes with Black students who didn’t seem to have any difficulty with academics? By the superior-standards rationale, Black students either were academically hamstrung and thus worked harder to achieve the same goals as we white students did, as evidenced by their presence and academic success, or they weren’t academically hamstrung at all. That meant we were fed lies to continue a racist agenda. Furthermore, despite the rhetoric in white Citizen’s Council pamphlets and bulletins that praised the quality of their all-white schools, the Citizens Council education system was hardly superior.

The curriculum at our academy lacked variety and rigor. Upon reflection, I’ve questioned how teachers did double duty with little or no relative expertise: basketball coach/biology teacher, football coach/history teacher, English teacher with a minor in chemistry that qualified her to teach both classes. A minor in a scientific field is only about two or three full courses (fall and spring semesters), enough to get your feet wet, as it’s said. I don’t remember Magnolia covering racial history. The only discussion of Martin Luther King was the general public’s interminable outcry over having a holiday in his honor. For a school founded by the Citizens’ Council, we learned nothing about the white supremacist council’s warfare against racial equality (at least in the later years, though older alumni have mentioned guest speakers when the school was first founded); we didn’t learn about Rosa Parks, John Lewis, Freedom Summer or the Freedom Rides. We weren’t taught the ugly side of the Civil War or of the era of slavery in the South. This simply wasn’t discussed in our parallel, whites-only universe.

By the time my senior year rolled around, I’d taken every class I could and was bored to tears. We did have microscopes, though, and we were taught to write, fortunately. Our biology teacher did what she could. Our math teacher, who seemed to teach every (decent) math class, was by far the best educator I’ve ever met. I loved most of my teachers; they were generally positive. Since we didn’t talk about race, I never thought of them as racist; I never thought of the experience as racist. Instead, it was more of a white silo. Sometime later I reconnected on Facebook with one of my favorite teachers from Magnolia. On a particular Facebook post, she entertained a discussion on whether Black people teach their children to respect police authority. I called it what it was, racist, but she and other contributors maintained their position. I discontinued our relationship. I’m sure there was a better way to handle it—that’s a question for all of us who come across a repugnant Facebook post by a friend or relative in these recent years—but she deeply disappointed me.

No school is a fit for all children, but I wonder if the sense of superiority that fueled the white academies was particularly hard on students who fell short of the entire rigid outward ideal of good looks, popularity, and athleticism. White people needed their own space to reach their superiority, according to the rationale of a need for whites to segregate. That potential rejection of anyone who was different, even if white, came across to my family early on.

My younger sister, who is physically and mentally challenged, didn’t remain at Magnolia. From my mother’s account, the school and she decided that public school might be more suited for her because they could provide services. I remember being called out of my class to go help after she’d have a seizure. Her teacher was petrified every time, and I was annoyed that they and other adults just couldn’t cope. Though I understand that our academy did not have special needs classes, public schools did. So, while public schools tried to meet all children where they were, my academy school could not fill this need. Directing my sister elsewhere made it clear (to me) which students the academy valued and those it didn’t. White-only schools were actually specifically for socially-approved white students.

I came up short on being socially approved too. Magnolia Academy was a Lord of the Flies experience for me. We had a Christian academy designation, but while we said morning pledges and prayers, it was anything but Christian in my experience. At our all-white, superior school there were degrees and cliques ranging up and down the socially-approved spectrum. I was one of the class nerds from first through twelfth grades. I was sporadically overweight, awkward and quiet. I was bullied and ridiculed or overlooked. I’m not trying to relive anything or ascribe blame, but I can’t really speak to the social aspects of the school because I rarely engaged in anything outside of the classroom. My family couldn’t afford prom dresses, a class ring or a senior trip. I was in band for a while, but when the horn players emptied their spit-valves over my head, other band members screamed at me for taking too long to learn the marching formation and still others locked me in the band hall, even band wasn’t fun either.

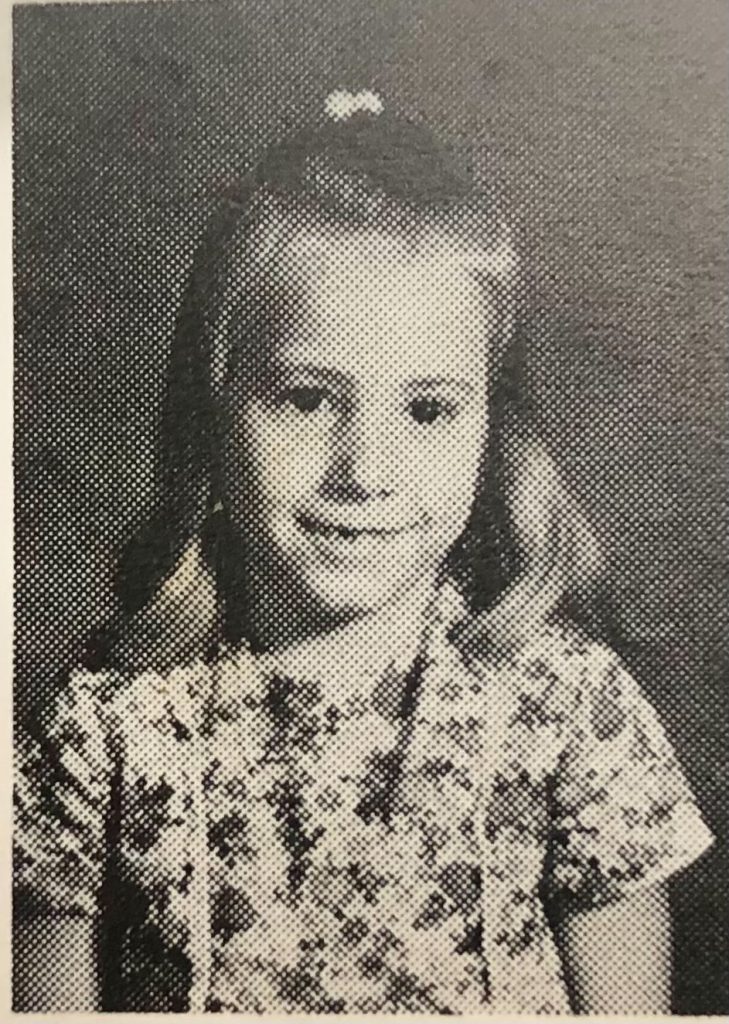

After my father’s death when I was in second grade, my family was probably the most economically strapped in the school. My mom couldn’t work because of my sister’s handicap and epilepsy, so we subsisted on Social Security benefits from my dad’s employment. We were poor to the point that the electricity was cut off twice. Why I remained in a private school is a mystery but is evidence of Mom’s belief or acceptance in the falsehood of white superiority to the point of sinking deeper into poverty for it. At my superior, Christian-associated academy, populated by neighbors who knew everything about everybody, our private family life remained a gossip bonanza for some throughout my twelve years there. It began when Dad died with suggestions that my mom would be forced to put me in the orphanage just down the road. For a while, Mom was industrious and found the funds for shoes and even for renting a clarinet. She grew our food, sewed clothes, and drove old cars into the ground. The clothes she made, purchased at garage sales or from a sales rack not meant for teens were hideous and no doubt added to my outcast status. Only my sister had regular doctor’s visits; I never told my mother when I got hurt and hid broken fingers and injuries. We both had maybe two visits to a dentist as children. My crooked teeth stayed that way. I finally had my vision corrected with a decent enough pair of wire-rimmed glasses that lasted until a classmate intentionally smashed a basketball in my face. After that, Mom insisted on a thick, ugly, plastic frame that wouldn’t break as easily. Eventually, I stopped getting my yearly picture taken by hiding in the bathroom. No one noticed. Everything about my life (finances, weight, clothes, teeth, glasses, whom my mother dated) was unrelentingly “fair game” to probably only a few people—yet it felt at times as if the whole school were talking. There were physical altercations also. I did consider suicide more than once and in my mid-teens went through a period of bulimia and anorexia. I realize now that bullying in a Christian-associated school system that based its existence on elevating one group over another shouldn’t come as a surprise. The descent down the slippery slope of determining who was “worthy” began at enrollment.

What saved me was that I loved learning and developed critical thinking skills. Ironically, being an outcast facilitated a sense of self-sufficiency. I longed for graduation and college. During my teens, I acquired a small microscope from a garage sale and was hooked on what would become a lifelong passion.

Eventually stress, clinical depression and out-or-character behavior took its toll on my mom. She died after a long illness when I was a 16-year-old junior. One student voiced his condolences.

One of the school’s aims, I assume, was to send students off to succeed in college. However, there was little engagement about post-graduate career goals, no counselor’s office to guide students and no organized career days. We had a school counselor only for a while. I remember one day lining up in front of a table under the awnings awaiting a turn to answer questions on our career goals, a dead-end exercise that resulted in nothing. Then again, maybe it did because, despite no resulting advice, I declared that day that I wanted to be a microbiologist. No one helped me with looking at colleges (certainly not out of state), or in applying for scholarships or even explained their existence. No, I didn’t ask for help, but I didn’t even know what to ask. I was shocked when Mississippi State University gave me an academic scholarship seemingly out of the blue.

If the school was wrong on race, there were signs of sexism too. I picked up an atmosphere of greater deference to and expectations of academically superior male students than female students. The two male valedictorians were pushed more and given opportunities to take additional coursework than I, even though I was the salutatorian of our class, and my GPA was near theirs. Slowly, I pushed myself past my lackluster educational start and, without parental help, without high school guidance, through loans and scholarships, became a doctoral-level virologist.

My point here is that nothing about this educational experience was academically, morally or socially superior, even though my own experience may have been unusually brutal. The academies simply taught the basics well enough for most of us to enter college if we chose that route. There was no comparison to schools with Advanced Placement courses, choices in electives or opportunities for extracurricular actives (e.g., clubs, arts) besides the basic three athletic choices and band. The academies were not a place where all students could find their niche.

I’m glad to have a chance to document my discontent with the academy experience and hopefully use it, in some small way, to move toward helping heal racial divisions. I’ve also taken the time to go back and learn some of the U.S. history we weren’t taught. I’m not saying this to sound self-righteous. I was naïve and never thought hard about it as a student there, but I’ve tried to learn some of the history and literature I should have learned at Magnolia. I’m embarrassed sometimes, even now, to read of less mainstream, but still giants in the civil rights movement, about whom I never learned anything. I wonder about something else, though: how many of my fellow alumni have tried to do the same? Who still embraces the system we experienced in that white Magnolia silo? From the scathing comments I’ve received in just discussing the Academy Stories project in our Magnolia alum Facebook group, I suspect many haven’t taken the opportunity to learn much of the history of racism in this country. One fellow alum told me that it was completely out of line to discuss critically examining on our academy experience in a group for academy alums.

The all-white education system did not prepare students for the world around us. Instead, it perpetuated a segregationist, apartheid system. It was wrong scientifically, factually, ethically, morally and socially. While it hurt our Black peers immensely, it also hurt the white students too. It robbed us of truth and a deeper knowledge of history. The often-spoken phrases by white people in the South, “Why can’t they just get over it?” or “It was a 100 years ago; it’s in the past” (That was a recent social media comment by one alumnus, which isn’t exactly a testament to our math education either) are fundamentally flawed. It’s not “their” history; it’s ours, and the all-white academy system robbed us of receiving an understanding of the total responsibility to learn about the mistreatment and wrongness of systemic racism and slavery. Fueled by their doctrine of superiority, these schools were philosophically unqualified to teach students to value human differences that make us equal and unique. Finally, they didn’t delivery what they claimed to offer – a superior education – taught under the guise of Christian values. I now use the experience in candid discussions to illustrate that people can change and learn despite what they’ve been formally and informally taught or not taught.

That August day of my college freshman year, when my Black classmate took his seat, my mediocre white-only academy bubble burst in a dizzyingly unmistakable reality-check. What had been the academy’s point? I don’t think there was one.

Dr. Catherine Bigger, known as Kitty Breeden in grade school, attended Citizens’ Council School Number 6, renamed Magnolia Academy, from kindergarten through twelfth grade in Jackson, Mississippi. She is a graduate of Mississippi State and Louisiana State universities and holds a doctorate in Microbiology and Immunology. Currently, she is a Department of Defense contractor as a subject matter expert for biodefense programs and the COVID response. She and her husband, also a biomedical scientist, live in Frederick, Maryland.

Thank you so much, Dr. Bigger.

Bravo on an excellent piece that should be widely read. Dr. Bigger has shown empathy and courage in writing about her experience. I am proud to know her!

I heard your story earlier tonight at Race Conversations zoom. Growing up in Ann Arbor, Michigan, in a racially integrated but socially self-isolated sect, I had a hard time visualizing your story and Fred’s. The article makes it clear. Congratulations. Good, plain talk from experience.

Thanks for sharing your story Dr. Bigger, though I’d imagine it was painful.