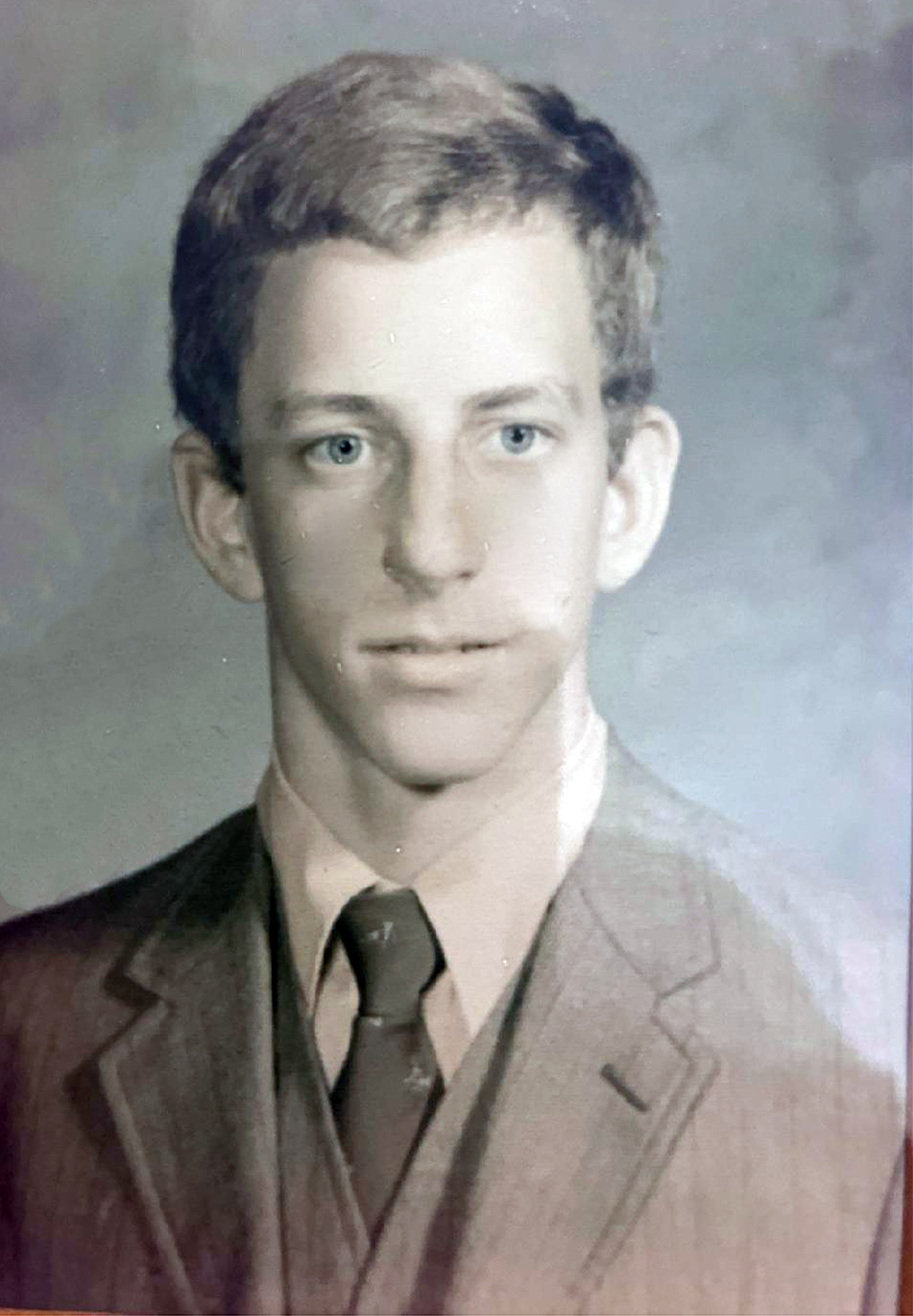

Peter Alford-Greenwood High School-Class of 1971-Greenwood,MS

My brother Tim Alford wrote about the legacy of jazz great Mulgrew Miller and the positive effect he had on our desegregation experiences growing up in Greenwood, Mississippi in the Seventies. Tim mentioned the “treacherous waters of the Yazoo River,” pocked with whirlpools. That’s where I begin.

We lived next to those waters, on River Road. Tim, our friend Joey Trigg and I could ride our bikes anywhere in town with the impunity of privileged white kids in the South. We would ride the two blocks down to Dad’s medical office at the corner of River Road and Cotton Street. From the WHITE entrance and waiting room at Dad’s office, you could look out on the Yazoo River. From the COLORED entrance, you could see across Cotton Street to the jail at the rear of the courthouse. Just beyond, the Keesler Bridge loomed a block further. This historic bridge broke the Yazoo River’s natural barrier between north and south Greenwood.

Peddling past the courthouse, onto the Keesler Bridge, along the walkway to the highest mid-point on the bridge, we would dismount and stare down into the Yazoo’s muddy swirling water pocked with those whirlpools, especially during winter floods. We discussed what it would feel like to fall in and be sucked into one of the whirlpools. We’d shudder, remount our bikes and ride on.

Crossing the bridge put us on Grand Boulevard, a two-mile oak-lined stretch of some of Greenwood’s most beautiful estates. At those houses, on summer evenings, Mulgrew Miller, as a precocious boy, learned his trade, playing piano for white peoples’ lawn parties catered by Nathan Jackson’s mother (Pre-integration, Mr. Jackson directed the band at Threadgill, the town’s Black high school).

At the north end of Grand Boulevard sat the Tallahatchie bridge. On the other side of the river, Money Road stretched out into flat Delta cotton fields. This was not the bridge of the pop song Ode to Billy Joe fame, where Billy Joe McAllister mysteriously dropped something off, according to Bobbie Gentry’s 1967 hit (by the way, Bobbie Gentry’s half sister Lynda Streeter played in the Greenwood High School band with us). That bridge had long since fallen down. The Tallahatchie, however, was where Emmett Till was thrown after white men murdered him. When Emmett Till’s body was found back in 1955, his body was taken to the Greenwood Leflore hospital. My dad’s partner Dr. Dick Meek was on call, examined the body and declared Emmett Till dead. Emmett Till’s capitol offense was that he whistled at a white woman. He might have lived if he had remained silent. Treacherous, deadly waters…

My friends and I had a stunt, which in retrospect was downright foolish. If no sheriff’s car was in sight, we would jump off the Tallahatchie bridge and not die. It was a frightful fall, and when we hit the murky water, if we let it, the lazy current would have floated us east to join the Yalobusha River, which turned into the Yazoo, looping back through the middle of Greenwood. Instead, we swam to shore, climbed the kudzu-choked bank to our bikes and headed back to town.

We rode around the front of the courthouse and the front of the Confederate monument. We would stop and climb up on the shoulders of the white stone soldier despite the pigeon droppings and survey traffic on Market Street. It was our favorite perch during the annual Christmas parade before we were old enough to be in the parade as members of the high school band.

Back on our bikes, we headed south on Cotton Street toward Jeff Davis, my white elementary school. Our final bike destination before lunch was the continuously running fountain of artesian well water on the Davis School playground. We drank from faucets on a large granite block covering the well. As I drank long and deep, the water swirled down the drain…

This is the start of my school story. I was woefully ignorant of the civil-rights movement as a third grader back when James Meredith entered Ole Miss in 1962 under the watchful eye of federal troops sent by the Kennedy brothers. Back then, I’d been impressed by the shiny black and gold full-rimmed sunglasses Mr. Meredith wore that day when I saw his image on TV. So much so, I wore a pair to school one day. At recess, the resident bully, let’s call him RB, a member of the sharecropping family of ten that lived out in the county, made fun of my glasses, laughing that I “looked like that Ole Miss n—-”. I did not answer back. I did not fight RB. I remained silent not from fear, but rather perhaps from a lack of conscience. As the bell rang to go back into Davis, I simply took the glasses off and never wore them again. Treacherous, swirling waters…

On our way home from Davis, we rode past the adjoining junior high school. In my memory, Greenwood’s integration started here, in in the fall of 1965, with a few brave Black students, long before the massive court-ordered integration of 1970. On my first day of seventh grade, I stood with my new north Greenwood white friends. My cousin was introducing me around. A car pulled up and from the back seat emerged Milbertha Teague, a smallish Black girl, and Marcel Gulledge, a taller Black boy. It surprised no one. Town gossip had focused on this strategic move by the NAACP for weeks. I don’t remember much about Milbertha, other than she looked scared. Marcel put on a braver front. He was carefully dressed, as if going to church: slacks, loafers, a vest over a neatly pressed white cotton shirt buttoned up to the neck. The two students stood by themselves until the bell rang at the corner of Cotton and Church streets, not even on official school grounds. There was a lot of glowering. No one walked over to greet them. No teacher. No student, including me. I’ve felt bad ever since for my silence and failure to do the right thing, for going along with the crowd, for my lack of courage. In 1964, my mother wrote a letter to the editor about the integration of the downtown Leflore Theater. In it she said, “Fear was riding where courage had walked, while conscience leaned and stood and considered” I wonder if she was also talking about me. Treacherous, swirling waters…

The traditionally Black section of Greenwood was literally across the tracks. We rarely rode our bikes there. Once Joey Trigg and I did ride to the Chinese grocery store, ostensibly to buy gum, but really to steal a Playboy magazine. We hid it in a hole we dug on the banks of the Yazoo.

Years later, I would cross those tracks, taking Mary the housekeeper home in Mom’s green Ford Country Squire station wagon. It was the deal I made in order to drive Mom’s car to school some days. Mary would always get in the back seat. One day, I asked her if she would like to sit in the front seat. Without hesitating she quietly said, “No sir.” A proud, middle-aged woman forced to be driven home by a 15-year-old boy, he calling her by her first name, and she addressing him as Sir. It didn’t seem right at the time, but I said nothing in response. Mary and I spoke not a word on the way back to her side of town. Silence. Treacherous, swirling waters…

In April 1968, Martin Luther King was assassinated up in Memphis. That night, my older sister Helen, a Rhodes College freshman, asked our uncle to drive her home, worried that the whole world was disintegrating. Later that year, Mom and Dad took Tim and me out of school to attend the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City. We saw Cassius Clay box, barefoot Ethiopian Mamo Wolfe win his heroic marathon, and Bob Beamon shatter the world long jump record. The event I remember most, however, was watching the awards ceremony in Olympiad Stadium and seeing John Carlos and Tommie Smith raise black-gloved fists in defiance during the national anthem. We left the stadium immediately, knowing we had witnessed history. When Colin Kaepernick kneeled to the same tune almost 48 years later, I thought not much had changed. Faulkner famously wrote “The past is not dead. In fact, it is not even past”. Treacherous, whirlpools, swirling…

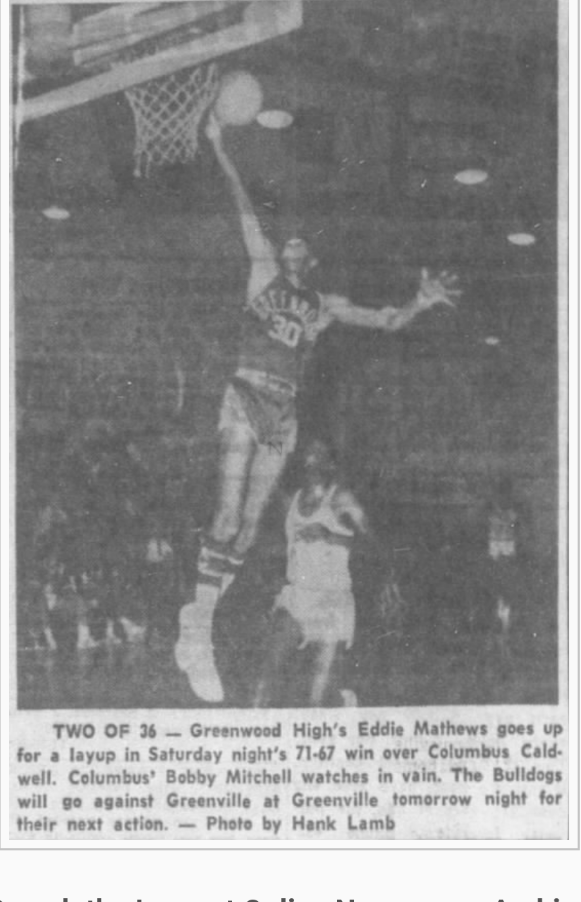

In 1970 I took Mom’s car across the tracks, telling nobody where I was headed. My new friend, Eddie “Slim” Mathews had invited me to play pickup ball with his friends on a court off West Henry Street. Slim was the star on the Greenwood High basketball team, having come over from the all-Black Threadgill High as part of massive desegregation. What Mulgrew Miller was to my brother Tim in his story was what Slim was to me – talented, sweet, happy. If he was bitter about the hand he had been dealt in life, he never showed it. Ours was an unlikely friendship between Slim, a hero athlete, and me, a band nerd.

I had band practice that night. After a quick supper, I left home early enough to get in one or two games. Jeff Capwell, the band director, drove by on his way to practice and spotted me on the court. Later, when I entered the band hall, Mr. Capwell was conducting “Aquarius”. He cut the band off and without looking up from the podium, said, “Alford. You’re late! Again!” Not the first time he had said that. As I was breaking out my French horn, he added “I want to see you in my office after practice.” Everyone looked at me.

Later, behind a closed door, Mr. Capwell lectured me on how foolish it was for a lone white boy to be playing ball with a bunch of Black guys. His concern was that if a fight were to break out, there would be no one to take my side. These words remain burned into my memory: “If somebody pulls a knife on you, you think your buddy Eddie would take up for you? Do you?”

Was that racist to say? That is for folks smarter than me to debate. At the time, I understood what he said to be well-intended advice from a respected authority figure worried about my welfare. I did not argue or protest. I was silent. I thanked Mr. Capwell for his concern and departed. I never again played basketball with my friend.

Slim led the Bulldogs to two straight North Big 8 championship games. In 1971, two Black guys confronted him on the basketball court and cut his hamstrings, hoping to end his career. They said he should not be helping a white school win games. They called him an Oreo—Black on the outside, white with in. Or so the story went. Fifty years later, I’ve tried over the last few weeks to find Slim to ask if what I heard was true. I haven’t found him. As close as I got was an old basketball teammate of Slim’s who told me he vaguely remembers an incident involving a knife. Treacherous, swirling waters…

On the last page of our 1971 Deltonian yearbook, editor Diane Howell included the following quote: “We have opened the door: do we have the courage to go beyond?” Some would say we have yet to pass through that door.

One of my favorite Martin Luther King quotes is “In the end, we will remember not the words of our enemies but the silence of our friends.” My fiftieth Greenwood High School class reunion is coming up soon. In 49 years, I don’t know that my African-American classmates have ever attended one of these functions. I was told that on one occasion, an invite was extended and declined by Black representatives. After the rancor and racism of this past election cycle, illuminated by Facebook comments from many of my right-leaning classmates, I considered not attending this reunion. The water seems too treacherous, pocked with whirlpools.

Where is courage or conscience in that inaction? Who, if not I, will raise a fist or bend a knee? What form if any will an epiphany or apology take? When will all be welcome? How can one ever hope for forgiveness or redemption? Who will break the silence, go through the door?

I will attend my fiftieth reunion. But when I go, what should I say or do? Or should I just stay silent?

Dr. Peter Alford has practiced pulmonary, sleep and critical care medicine for 40 years, academically at Wake Forest University Baptist Medical Center for 12 years and later in private practice. He is currently medical director of the Critical Care Unit and Respiratory Therapy at Catawba Valley Medical Center in Conover North Carolina. He attended Davidson College and the University of Mississippi Medical School.

Beautiful story. I see myself in everyone of these stories and have my own uncomfortable memories of when I too was silent. We aren’t silent anymore.

Peter,

I’ve seen you voice your conscience, heard you raise the moral questions over the last few years and I’m so happy you are telling your story. Story let’s us walk in your shoes, and we experienced your empathy for others. Made us think of our own everyday silence that harms others.

Keep pulling on the right questions and telling your story.

Money street, Cotton Street, Church Street.

Treacherous waters, for sure! Nicely told.

Thank you, Dr. Alford. I love this project and I love your story. I worked as a reporter at The Commonwealth just a few years ago and was constantly amazed at how little appeared to have changed with the exception of Black elected officials and the infiltration of some formerly all-white North Greenwood neighborhoods by Black families. . Pillow Academy and Greenwood High School could not be more separate and unequal. And the north-south divide still exists for the most part. So important to continue telling the truth about this, despite all the good people and good intentions. Until that divide is bridged in a way that recognizes the persistent legacy of segregation, neither Greenwood nor the rest of the Mississippi will move forward. Now much of the nation is falling in line with Mississippi politics and what we know to be a losing proposition, making America great/white-dominated again.

What a moving, honest and humbling story! Beautifully written.

Thank you, Dr. Alfred.