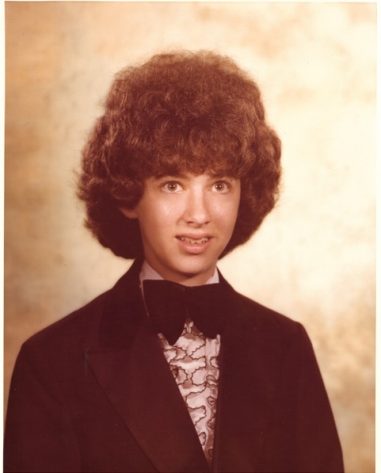

Dusty Rhodes-Nathanael Green Academy-Class of 1978-Siloam,Georgia

During the summer of 1971, my family moved from the bustling city of Charlotte, North Carolina to the quiet woods and pastures of Siloam, Georgia, where my sister and I enrolled at Nathanael Greene Academy.

I knew that NGA was a fairly new school. I just didn’t know exactly why it was a new school. My first day at NGA, I was asked by more than one kid if I was a Yankee or a Rebel. I didn’t know what they were asking, or even why. I was a sixth grader, with no knowledge of the Civil War. The Yankees were a baseball team in my world. I asked them what they were, and then went along. I just wanted to fit in with new friends.

I wasn’t expecting so many questions from strangers, but I did my best. I didn’t speak with their rural Georgia dialect, and that’s probably why they suspected that I might be a Yankee.

For this wide-eyed sixth grader in 1971, NGA was just school, with classrooms, teachers, homework, tests, report cards, and P.E. Another difference for me was this was a K through 12 school with a total enrollment of just over 300.

My previous school in Charlotte was grades 5 and 6 only, with at least the same number of students. And it was a racially integrated public school.

In the old, abandoned Siloam city school building that was deeded over to this new private “academy” for the bargain price of one hundred dollars, we mostly learned what the public school kids learned in their schools, despite ours being deemed “a place of higher learning.”

At NGA, we recited The Lord’s Prayer every morning after the Pledge of Allegiance and a student-led devotional. The devotional was never a class discussion. Most of us took the easy way out, and read the shortest passages we could find, trying not to giggle as we read.

In high school, a Bible studies class was offered. I smile at the memory of Rev. Jim Ransom’s Old Testament class, where he would write the names of important characters on the board, then draw a line through their name when they died. For what it’s worth, that class has helped me more than once with Jeopardy questions.

Then there were the assemblies and pep rallies, where we always sang the alma mater, in which we declared NGA’s “ideals are worthy.” The concept of a school song was new to me, but it quickly became a source of pride for me at NGA, as it was for everyone else. I also recall one assembly that took place in the school’s auditorium, where we were led in a rousing rendition of “Dixie” by the music director of one of the local churches.

In my eyes, racism in the rural south in the Seventies was demonstrated in a publicly outrageous way by the likes of J.B. Stoner, who unsuccessfully ran for governor, lieutenant governor, and U.S. senator as a segregationist.

I couldn’t see the dotted line between a segregated private school and a segregationist politician who callously tossed racial slurs in the political ads I saw on TV.

I’d heard the N word in Charlotte, from one of my friends, and my mom let me know that it was not a word she wanted to hear. Let’s just say that I heard it a lot more on the playground in rural Georgia, and whenever I brought any of that home with me, my mom continued to show her disdain for it.

The Roots TV miniseries aired in 1977 during my senior year. I worked a part-time job at the local nursing home. A young Black employee once asked me if I had watched it, and wanted to know what I thought about it. The conversation made me uneasy. I probably stammered that slavery was awful, but I was very uncomfortable with that conversation.

I shared the story of the Roots conversation in my 12th grade government class, and the teacher quickly shut me down. I can’t remember her exact words, but I can remember that she thought it was ridiculous that I had been asked such a question. She didn’t want to discuss it further. She was not prepared to take our class to a place of “higher learning” on that day.

If my thoughts on my NGA experience sound complicated, they really aren’t. My sister and I came in as outsiders, graduated, and left for college. I think both of us have compartmentalized the experience. As an adult, Siloam became an exit on I-20 that I looked at as I drove by on trips. I took that exit once and showed my wife and kids where I went to school, but it didn’t invoke any emotions at the time. If anything, I was surprised at how little it had changed.

Let me be clear, I loved my friends and teachers, but in the last few years I have come to a place of reckoning. We were all on the wrong side of history.

It’s the very idea of NGA’s existence that troubles me. I could have known many of those same classmates and teachers had everyone accepted the integrated public school, right? My fifth-grade year at an integrated school in Charlotte didn’t leave any scars on me.

I graduated from NGA in 1978 and left for the big city of Atlanta, where I earned an electrical engineering degree at Georgia Tech. My lifelong friend and fraternity brother, Russell, went to Greene County High School, where I’d have gone but for the existence of NGA, and also earned his electrical engineering degree at Tech. What exactly was accomplished by creating that private school in tiny Siloam? What did I gain that Russell didn’t gain a few miles up Highway 15 in the larger town of Greensboro? I can’t come up with a reasonable answer.

I was introduced to the concept of “seg schools” by my wife. She shared an article, authored by a writer from Mississippi, Ellen Ann Fentress, who wrote among other things, that “in 1964, the state had less than 20 private schools. The number rocketed to 236 by 1971.”

I was completely oblivious to the fact that my secondary school experience was part of an organized movement, all founded for the same reason at essentially the same time. Community leaders across the South circled the wagons and essentially told the government that you can’t force our kids to go to school with Blacks.

The reality of the situation is undeniably simple. The Brown vs. Board of Education ruling came down in 1954, but the Deep South defiantly ignored the ruling until the Supreme Court handed down a new ruling with a deadline of January 1970.

It was the date that grabbed my attention. If you look at the NGA website today, you will read that “Nathanael Greene Academy was founded in 1969 as a traditional college preparatory school.”

Time has a way of polishing narratives, but the founding date is the smoking gun. It’s not a coincidence.

Traditional college preparatory school? I’m just guessing, but I’d say that half of my classmates didn’t go to college.

As I read Fentress’s essay, I learned that the prevalent mascots of these academies were Patriots and Rebels. At NGA, we were the Patriots. Down the road in nearby Sparta, lived the John Hancock Academy Rebels. As I read the other stories submitted by alums to The Admissions Project, any feelings I may have held about our situation being unique or otherwise special were rapidly disappearing.

I began my dance with writing in early 2021, and so when I read these stories, I had to write my own, though I didn’t submit my essay to the project. Last weekend I read a follow-up Salvation South essay from Fentress https://www.salvationsouth.com/a-completely-white-world-admissions-project-mississippi-ellen-ann-fentress/

The Admissions Project has expanded to also include stories from alums from integrated public schools too.

Fentress mentioned that she still hadn’t heard from academy alums in Georgia, Alabama, South Carolina or Louisiana. I reached out and told her that I had a Georgia story.

Schools in our region were mostly named after historic figures who were also the namesakes of the county the school resided in. I couldn’t find a single source of information of the private schools in my day, but I remembered the school names, and looked up the founding dates of Samuel Elbert (1971), George Walton (1969), Thomas Jefferson (merger of Stapleton and Bartow Academies, both founded in 1970), Edmund Burke (1960, first graduating class was 1971), John Hancock (1966), and of course Nathanael Greene (1969).

Other schools that I remember in our region were Gatewood Academy (“…for over 50 years…” – do the math), Briarwood Academy (1970), and Brentwood Academy (1969).

Fentress recounts in her essay that she and her classmates didn’t even know the name Emmett Till, even though he was lynched “in her hometown’s back yard.”

Our class took a field trip in our own back yard to the birthplace of Alexander H. Stephens, but it would be roughly fifty years later that I would learn of his infamous “Cornerstone” speech, in which he clearly articulated that the cornerstone of the new Confederacy “rests upon the great truth, that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery – subordination to the superior race – is his natural and normal position.”

One tactic that whites use to help reconcile the past is the fallacy of relative privation. “We may have been a little racist in Georgia, but Mississippi and Alabama were a whole lot worse.” Of course, that’s just not true. There’s nothing “a little racist” about Stephens’ declaration of white supremacy.

There was nothing “a little racist” about thousands of all-white private academies suddenly springing into life all over the South. That wasn’t the first time that whites would push back against doing what is right in the pursuit of equality for all, and it wouldn’t be the last time. Mark Twain once said that “History never repeats itself, but it does often rhyme.”

There was nothing “a little racist” about the vigilante style 2020 murder of Ahmaud Arbery in Glynn County Georgia. The murderers of Emmett Till were acquitted by an all-white jury; Arbery’s killers almost escaped investigation and prosecution from corrupt local law enforcement intending to protect their own.

I had to get my story down on paper, so I could analyze, and learn something from it. And who knows, maybe something I say could resonate with someone else. We need to have these conversations. Confronting the reality of my private academy education was and is an important part of this reckoning.

We can’t change the past, but we can learn from it. Of course, we can only learn from it if we are first willing to learn it. I’m ashamed to admit that for too many years I selfishly wasn’t interested in learning more about things that didn’t impact me. Just as I tried to fit in with my new classmates at NGA in 1971, I spent most of my adult life trying not to rock the boat. Like most adult white men in the South, I voted with my wallet.

My bubble burst when I outed myself in support of Colin Kaepernick. On social media, I shared the radical idea that white people needed to lean into his position on systemic racism. My friends pushed back. The conversation just couldn’t get beyond patriotism. It was a hard stop.

The hard stops we face today are too often drawn along the same ideological boundaries that were drawn in 1970, which were too similar to the cornerstone of the Confederacy.

We naturally feel a need to honor our parents. I lost my father in 1979 and never got to know him as an adult. I lost my mother in 2019, but I know where she stood on racial justice issues. I think she would agree that “the academy solution” was a mistake that we all made. We should all just own up to it, be willing to learn more about it, realize the impact that it had on others, and try to do better going forward. That was her approach to life.

I reject the notion that my Seventies segregated education was in any way patriotic. To argue otherwise is to proudly fly the confederate flag. If we accept the myth that our segregated academy was formed to create a better educational experience, then what message did that send to the students that were excluded based on their skin color?

NGA’s alma mater can be found on the school’s website today, but the melody and the lyrics never left my memory. It states that “like Patriots of old, we will hold high the flame of knowledge and truth, and of freedom and right.” The second stanza begins “Your ideals are worthy, your standards so grand. The noblest, the greatest in all our fair land.” It closes with a resounding pledge of loyalty.

There was nothing noble or fair about NGA. Its founding ideology of segregation is just ugly and based on ignorance and defiance, not knowledge. Those lyrics living in the permanent memory of my brain now ring hollow.

I tried so hard to fit in at my new school in the fall of 1971. Writing this essay makes me feel as if I’m still the outsider.

I guess that makes me a different kind of rebel.

Dusty Rhodes is a healthcare information technology professional in Tallahassee, Florida. He is a lifelong learner, hand tool woodworker, and blogs at http://dustmanwoodworks.wordpress.com Follow him on Instagram: @dustmanwoodworks

Thank you for your story, and yes, it resonates mightily!