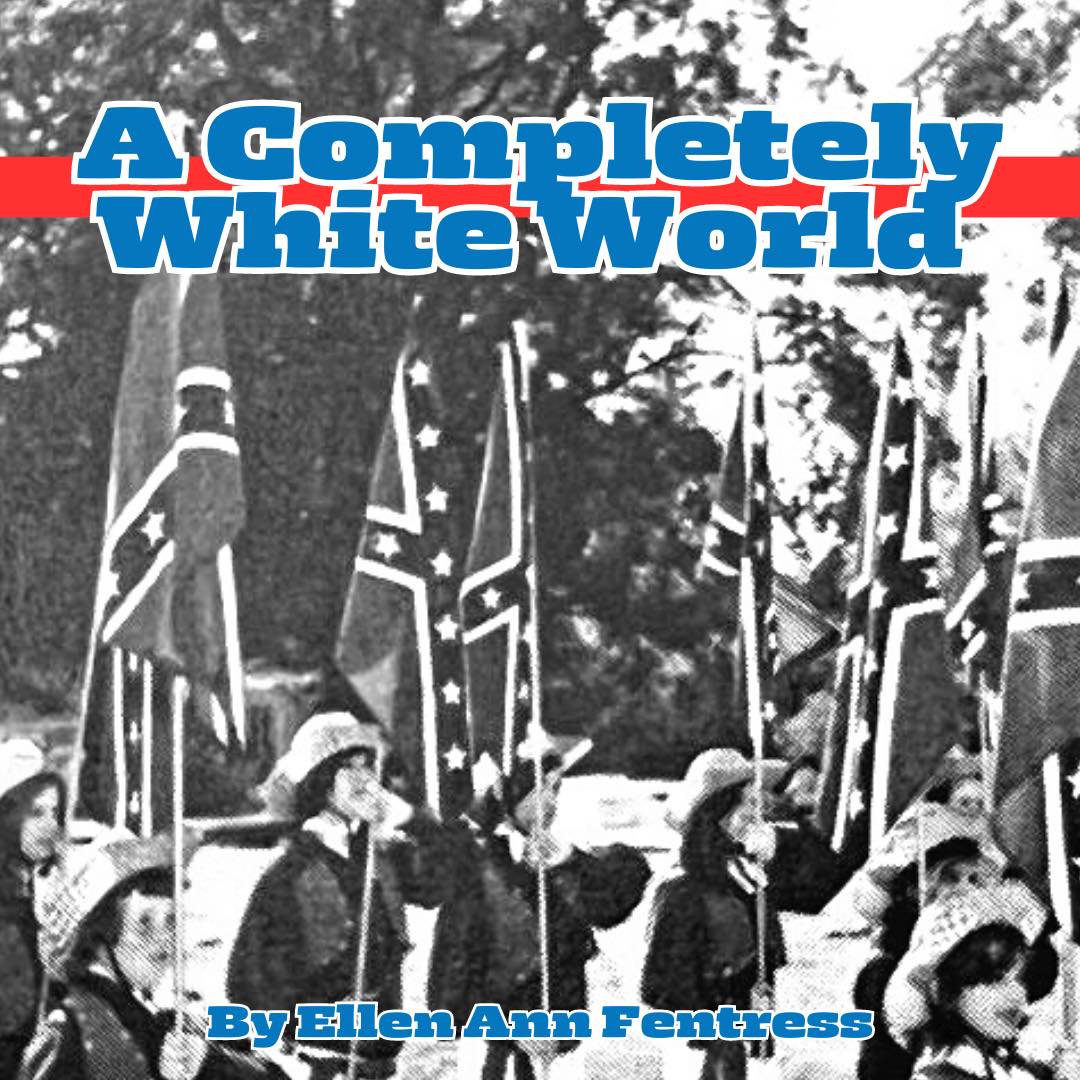

Ellen Ann Fentress–The Admissions Project editor

It’s a truism that we learn what we know by sitting down and writing about it. That’s been the case for the 37 essayists on the site so far. Same for me, thanks to Salvation South asking me to write about The Admissions Project as it nears year four. Good news is that by the mention in the piece of the lack of first-person stories to date from Louisiana, Alabama, South Carolina and Georgia, a few new essayists will be sharing their accounts soon. Let’s talk about sharing yours: info@admissionsprojects.com

Here’s A “Completely White World,” my August 11, 2023 piece for Salvation South https://www.salvationsouth.com/a-completely-white-world-admissions-project-mississippi-ellen-ann-fentress/

In the late 1960s, white parents all over the South wanted to keep their children in racially segregated schools, and they set up thousands of segregation academies. I am a graduate of one—Pillow Academy in Greenwood, Mississippi.

In Weejuns and a Pepto-pink hair bow to match my pink A-line minidress, I began Pillow Academy as a second-semester eighth grader in 1970. It was the exact moment the fed-up U.S. Supreme Court scrapped the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education directive for segregation to end “with all deliberate speed” to issue a hard 1970 deadline in Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education. Fifteen years of stonewalling came to a halt in my hometown of Greenwood and around the South. White families like mine fled public schools. At their 1970s apex, an estimated four thousand white-flight academies opened in eleven states, pulling 750,000 of us out of public education. Across the region, white Protestant churches offered their buildings for makeshift classrooms to schools created overnight until bare-bones corrugated steel academy buildings could rise up close by.

But that was then and this is now, right? Yes and no. Scores of overnight academies did eventually close. But three generations later, Pillow Academy and hundreds more legacy academies are still embedded in Mississippi communities and elsewhere in the Deep South. This summer, I read that the singer Jason Aldean and Fox’s Nancy Grace came out of Windsor Academy in Macon, Georgia, also birthed in 1970. I’d be about as surprised to hear a Southern town has a legacy segregation academy as that it has a water tower, a Baptist church, or a Dollar General. None of the academies I know of admit to their heritage, but a telltale indicator is a founding date between 1960 and 1970.

More than I care to admit, the academy mindset lingers inside my skull. I found out so in 2018. My wakeup came via a local story in the Jackson Free Press during Cindy Hyde-Smith’s first campaign to become one of Mississippi’s U.S. senators. The piece said she was a 1977 graduate of the all-white, now-defunct Lawrence County Academy. Running alongside the report was a black-and-white photo from The Rebel, the academy’s 1975 yearbook. The future senator/then-cheerleader sprawls on her tummy with the rest of her squad, chin resting on her fist. A male mascot stands above the girls, gripping a Confederate flag. Multiple national outlets snatched up the news and photo.

I was surprised that the nation was surprised. Go down the list of middle-class, middle-aged Mississippians like Hyde-Smith and me, and you’ll find that as many of us are alums as not—at least in my white world. There are writers like Donna Tartt, Kathryn Stockett, Steve Yarborough. There’s TV anchor Shepherd Smith, actor Sela Ward, former Mississippi Governor Phil Bryant and current Mississippi Attorney General Lynn Fitch, whose office last year led the Supreme Court case that overturned Roe v. Wade—Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization.

The idea of a segregation academy struck those elsewhere as blatant and outrageous racism. What had immunized me from any sense of shock? I’d normalized the academies’ presence. I’d taken them for granted—an indication of the whiteness I’d soaked in.

THE FIRST DAY OF SCHOOL

Let’s go back to that first school morning in January 1970. That’s when thirteen-year-old me stepped through Pillow’s front door in Size 8 penny loafers onto the hallway’s bare concrete floor. Back then, I didn’t think fleeing integration was either good or bad. What brought me to the academy, instead, was the prospect of my two best friends going missing post-holidays from our public school. As the court deadline and Christmas break approached in December, my two BFFs reported that they were definitely academy-bound in January. So were many others at blond-brick Bankston Elementary, near the Tallahatchie River at the town’s north city limits. I couldn’t imagine lunchtime or hanging out in the hallway of ’50s-modern Bankston without my pals. If they were going to the academy, so was I.

That’s completely true, but what’s also completely true is that it was a setup. My father admitted later he’d been as determined to move me to Pillow as my two friends’ more forthcoming parents. He and my mother had quietly squared away the Pillow paperwork and tuition check outside my earshot because they wanted my choice to simply look like my own decision when January came.

And Pillow Academy was my choice. That wordless orchestration of my academy entry—managed out of sight to look natural and easy—rings true to the time-tested silky way whiteness slides along. The less open the discussion, the less chance for ifs and buts. If you’re in charge of the dominoes, you get to line up how they’ll fall. Newspapers were full of integration headlines. In capitols across the South, hot-mouthed legislators passed pro-academy bills by the fistful. Yet at my house over the 1969 holidays, there was only The Andy Williams Show’s Christmas special on the NBC station out of Jackson and the beating bass of “Come Together” by the Beatles on WDDT-AM out of Greenville, the irony of the words unnoticed. My switch to the academy was a done deal.

White adults were enraged at the federal court’s order to redraw the town’s school districts for comprehensive integration. The fury was as much about the audacity of the courts to flatten whites’ sense of control—of course, no one brought up the fifteen years of stonewalling that led to the deadline—as it was about integration itself.

A Pillow Academy promotional brochure hinted at respite for crushed white psyches. The 1970 flyer didn’t quite say that Pillow offered a white space for white talk, but it did say this: “Class discussion can be more fruitful, and opinions may be expressed with less likelihood of causing embarrassment to social or ethnic groups.” Local whites could retrieve something of their sense of agency—at least inside the new steel building in the former cotton field west of town.

I can’t say I remember any terrible racist teaching in my concrete-block classrooms. Then again, if your whole carefully segregated school is a statement, why would that be necessary? We existed in a white silo with the resulting message that none outside must matter.

My awareness did sharpen in a year or two, but just a tad. It wasn’t that I’d started wrestling with the way my academy stripped Greenwood’s public schools of white interest or resources. In the spirit of that 1970 brochure, I gnawed over a potential politeness pitfall. What if a Black person were ever to ask me where I went to school? My answer would be nothing short of a slap in the face. But who was I kidding? The likelihood of my ever being asked that question was pretty much zero. In my Mississippi Delta county, although its population was fifty-eight percent Black at the time, I didn’t know a single Black teenager. I lived in a completely white world.

LET’S TALK

It wasn’t until forty-nine years later that I decided to write publicly about the conscious and unconscious ways my segregated schooling shaped me. I approached Salvation Southeditor-in-chief Chuck Reece, who was then the founding editor of The Bitter Southerner, about an essay I’d written called “Are You a Seg Academy Alum, Too? Let’s Talk.” It was published in June 2019.

Emails from seg-academy alums from across the country swamped my inbox. Others were as unsettled about their schooling as I. The piece hit home. What about a website to collect our stories? I wondered. The Mississippi Humanities Council greenlighted a grant when I asked. To launch, I recruited six writers who’d been seg-academy graduates. Actually, I’d long been tucking away the fact of anyone’s academy bona fides whenever I learned about them. The project launched. Before long, The Washington Post, Slate, Forbes, The Hechinger Report, Mother Jones and The American Conservative featured the site. In four years, there’s never been a word of response or input from any of the academies themselves.

A year after the launch, the original project name, The Academy Stories, expanded to The Admissions Project: Racism and the Possible in Southern Schools, a platform capturing public-school integration stories as well as pieces about experiences in segregation academies. White-weighted integration was, in many communities, as under-discussed as academy life. Traditional Black schools were often shuttered, and students shifted to white schools that made no effort to support students and teachers as they navigated the change. There’s a third story category, too: the accounts of families who were able to move away and did, choosing to leave a town with a racial school chasm. I’d like to see a study track the economic fates, decade by decade, of towns with nearly all-white private academies and all-Black public schools. That’s not a lure to move somewhere.

After four years, The Admissions Project has published thirty-six first-person stories and had tens of thousands of readers. A digital photo gallery launched this summer is, I hope, the start of an archive for readers to share their own images. Four additional stories are in the editing stage now, as is a three-episode podcast. Send yours; we always welcome more. First-person stories have come in primarily from Mississippi with others from Tennessee, Virginia and North Carolina. Still waiting on you to share, Alabama, Louisiana, Georgia and South Carolina. The stories are there.

I wait on folks a lot, actually. I’ve had to recruit thirty-four of the thirty-six essays on the site, which accounts for ninety-two percent of the stories. Only two have arrived out of the blue from then-strangers. For every academy alum essay on the site, there are dozens of potential writers who say no to writing. First, some see nothing wrong with their academy past. I’ll assume the writer of this recent email knows how to spell but pressed SEND prematurely: “I started at Starkville Academy the first day it opened. Our school was founded by exceptional men in our community for the purpose of making sure we got an education to prepare us ti [sic] move in to the heft [sic] level. Never once was there any racial overtone our encouragement [sic].” I invited the writer to send a full essay to the site, but no word back.

Then there are the squeamish. Many alums are unsettled about their high school history but afraid to write about it, due to the risk of public or family blowback. Two graduates in particular thriving in D.C. jobs as public progressives—both non-Mississippi Southerners—gave hard no’s when I checked if either would write. For many with academy pasts, the brakes are internal. Publishing their stories feels disloyal to parents who “only wanted the best for me.”

WALK IN OTHERS’ SHOES

Yet isn’t that what all parents want? I feel a little uneasy on that parent score myself. I also know, though, that it’s white fragility on my part to prioritize the feelings of deceased white people, including my much beloved ones, over needed conversation in 2023. I am responsible for what I do in the present, which is to both document the truth and hold my parents’ memory close. And for what it’s worth, my academy teachers were never anything but nice to me personally, either. Refer back to the earlier point about how easy it is to be caught in the silky web of whiteness. The fact that, one on one, everyone inside that Delta metal building was well-intentioned and kind to me makes it harder to speak out. It’s the system, history, and the inarguable community damage of academies that are The Admissions Project’s focus.

What are the site’s outcomes so far? The first-person accounts are starting to show up in academic research. Three new history books cite the project (The Injustice of Place: Uncovering the Legacy of Poverty in America by H. Luke Shaefer, Kathryn Edin and Timothy Jon Nelson, American Crusade: How the Supreme Court Is Weaponizing Religious Freedom by First Amendment attorney and author Andrew L. Seidel and Southern Beauty: Race, Ritual, and Memory in the Modern South by Mississippi native scholar and teacher Elizabeth Bronwyn Boyd). Multiple theses are quoting the site, as is at least one undergrad syllabus (at Trinity College in Hartford, Connecticut). MSNBC used project screen shots when Roe’s 2022 overturn spurred the night’s dive into the history of U.S. conservative mobilization. The Mississippi Historical Society gave the project a 2022 award of merit, while Admissions essayists have been on multiple webinars in Mississippi and elsewhere. There’s a direct online portal to the site through the Mississippi Free Press home page.

“The fallacy of white supremacy leads you to believe that what is there is better.”

The Admissions Project stories convinced New York researcher Elke Weesjes to change the focus of her project in progress. A year deep into research funded by the Mellon Foundation and the American Council of Learned Societies, the City University of New York teacher was aiming to examine the experience of children of Ku Klux Klan members from 1960 until 2000. Her original focus was “what it was like to grow up on the political fringes of American society.” She’d written a similar 2021 book Growing Up Communist in the Netherlands and Britain: Childhood, Political Activism, and Identity Formation by Amsterdam University Press.

In February, while Weesjes was in Mississippi seeking out adult children of Klan members, we met by chance at a library circulation desk. Once Weesjes read The Admissions Project accounts of academy alumni, it reframed her understanding of white supremacy’s ordinariness in the twentieth century South.

“I came to the realization that whatever I saw up until then as something unusual was actually very normal,” she says. “You can call it a quiet racism. It was kind of upsetting to me on the one hand because I thought that I had a sample of kind of unique experiences.”

Weesjes’s new working title is “Children of Segregationists: Growing Up White in the Deep South.” Several of the site’s essayists have sat for interviews with her.

While all of the above are proof The Admissions Project is read and used as a primary document of history, I also have hopes not so quantifiable. The site simply provides a space to walk in others’ shoes and to swap stories, hopefully shifting readers’ insides a bit for doing so. The Admissions Project is in the “hearts and minds” business, to use the 1954 Brown ruling’s words.

Von Gordon, head of the Jackson, Mississippi-based racial reconciliation nonprofit the Alluvial Collective and a Jackson public school graduate, was fascinated to go inside seg academies via the accounts. He’d assumed life in the schools was smooth.

“The fallacy of white supremacy leads you to believe that what is there is better,” says Gordon. The segregation-academy essays illuminate the often makeshift locations and academics within. The narratives show that private-school whites were often as unmoored as public school students in transition. “There was a hell of a lot of trauma there,” says Gordon, who is Black. “For white kids who had to leave their schools and go there—they grieved.”

Gordon was also intrigued by novelist Steve Yarbrough’s account of his father’s annual struggle to raise the tuition money to keep him in a segregation academy, because both Yarbrough and Gordon grew up in Sunflower County, Mississippi. As a child, Gordon attended Head Start in the town of Moorhead, eight miles away from Indianola Academy, Yarbrough’s school.

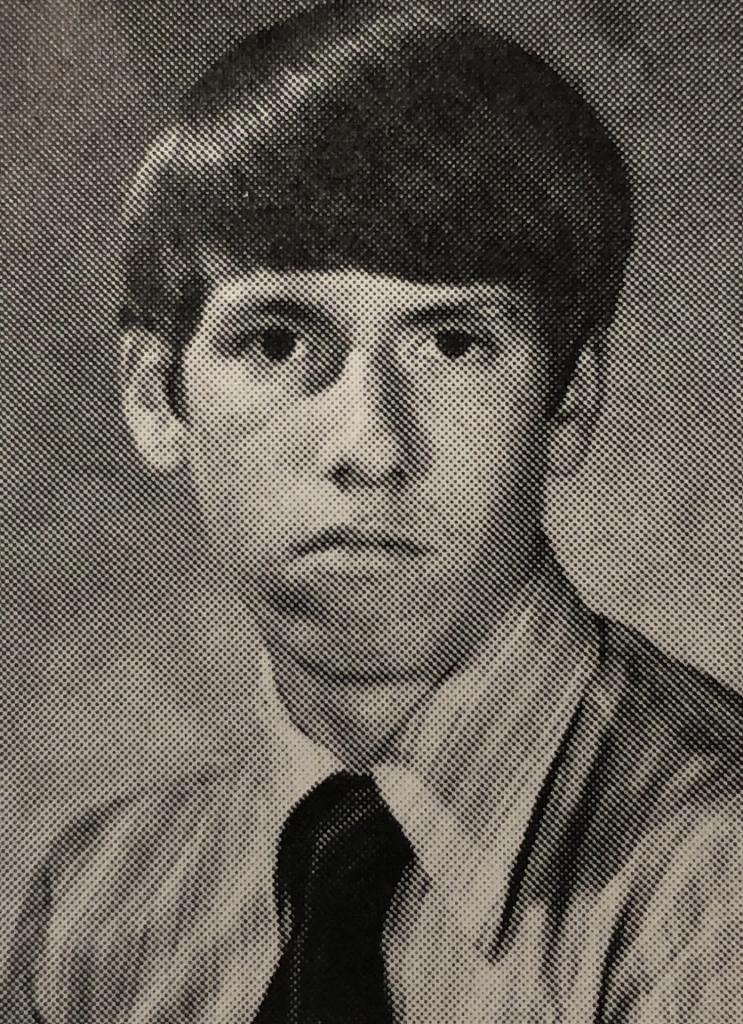

Mississippi novelist Steve Yarbrough in his Indianola class of 1975 picture (courtesy of The Admissions Project Digital Archive)

“I think about dreams that had to be deferred because of that cost element,” Gordon says after reading Yarborough’s essay for The Admissions Project.

Writing his own academy account nudged Stuart Levin to lean in harder to anti-racism efforts on his University of North Carolina-Raleigh medical campus. After contributing “We All Knew What It Was” on his time at Beeson Academy in Hattiesburg, Mississippi, he kept researching. He contributed an academic paper to the Journal of Mississippi History, winning the 2022 article of the year prize. Levin, a clinical professor of medicine at UNC School of Medicine, wanted to be part of the stepped-up efforts at teaching about systemic racism’s impact on health disparities, now included in the education of third-year medical students.

“The essay further spurred my work to enhance the curriculum on health disparities,” says Levin. During orientation, med students tour southeast Raleigh to see the effects of redlining and its aftermath, including visiting the site of the closed St. Agnes hospital and Leonard Medical School. Levin’s work is part of an overall focus at the UNC School of Medicine on examining health equity, he says.

“KEEP DOING WHAT YOU’RE DOING”

People who oppose The Admissions Project typically come from two camps. First, there are the offended, who declare there’s nothing to see here. The academies’ typical sanitized origin stories claim that in the late 1960s there was a realization of the local need for “quality education.” They buttress that narrative by observing that local public schools are in shambles. This one-two branding is so effective and so longstanding that, even after the multiple talks I’ve done, I’ve had younger academy alums and teachers declare that they’d never heard before that dodging integration was the actual history of their school. Gen X alums, who were either preschoolers at the time of integration or born after, can be particularly insistent about their academy’s blamelessness. A key to their defense is that most academies have had Black students—albeit in small numbers—since the 1990s.

Douglas Blackmon, a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist who grew up in Leland, Mississippi, noticed the particular pushback of academy Gen Xers in interviews for his upcoming PBS documentary The Harvest. The film examines the results of a half century of integration in Leland. It’s set to air on PBS’s American Experience on September 12.

“It’s pretty fascinating, though in hindsight it should have been more obvious to me, how different the perceptions of everything were/are between those who were old enough to know what was going on at the time, and those of us who weren’t,” he noted in an email. “The perception I have most consistently encountered from anyone my age or younger who attended the academies is that it is totally preposterous to suggest the formation of Leland Academy, Washington School, etc. etc. had anything to do with race.”

The second critical camp holds that talking about the racist past in general is negative and damages the present. After reading the site, a childhood acquaintance of mine told me so. My acquaintance (let’s call her Olivia) is white and actually did stick with Greenwood public schools at the moment when I went to Pillow. Even so, after reading the site, she texted me: “These stories make me so sad. I want you to see good news. Come to my Bible study.”

So I did. When I pulled into the parking lot of the big suburban church outside Jackson, I saw lots of late-model SUVs. Inside, women in smart cotton separates, Bibles in hand, scattered to their small group studies. In the spotless upstairs Sunday School room where my group gathered, there were about a dozen white women and three Black women. We sat in a circle of folding chairs, and the morning leader prepared to start. I came to observe and learn, not speak. That’s just as well, because the morning’s Ephesians passage made me cringe: “Wives, submit yourselves unto your own husbands, as unto the Lord. For the husband is the head of the wife” (I’m big on Bible context. I’m down on both misogyny and goat-sacrifice scripture, too). I swallowed hard, scanning our circle to see the others’ reaction.

“Well, someone has to be in charge,” a tall participant who was white offered mildly, Bible open on her knees. No one disagreed. Everyone’s expression looked serene as the discussion moved along. Eventually came the closing prayer. Everyone kindly invited me back for the next week.

I asked one of the Black group members (I’ll call her Patricia) if she had time for lunch. At a taqueria down the street, we broke the ice in the typical way: we traded information about our children. I learned her husband was a retired military officer, and they’d lived around the world. We both had Delta family roots. After a while, I told her about The Admissions Project. I explained how Olivia, who’d invited me that day, worried that too much discussion of the racial past marred the positives of the present. What did Patricia think? Neither she nor Olivia had resisted that morning dose of the Apostle Paul. Patricia paused, taco in hand. I wondered if I’d marred our talk and tacos by bringing up race. Was she offended? A moment later, she nodded her head.

“You should keep doing what you’re doing,” she says. In fact, for emphasis Patricia kept nodding, her taco hovering over the plate while she spoke again. “That history is important.”

OPPORTUNITIES: SEIZED AND MISSED

For Black people who share their stories with The Admissions Project, their work is often an act of generosity—one that comes with an emotional price.

In “It Was on the Backs of Black Students,” author Ralph Eubanks reflects on his confusion and anger at white peers leaving Mount Olive High for the signless red brick academy perched near U.S. 49.

“What led to my bewilderment and anger was that, every day, I experienced how the burden of integration fell squarely on the backs of Black students,” he wrote. “From the day Black students walked through the schoolhouse door, we were treated as unwelcome interlopers who had to prove ourselves worthy of just being there. Our arrival was greeted by protestors carrying brooms and mops, telling us that they would clean us out of the school like trash.”

A few months later, Eubanks reflected on penning his story.

“Perhaps the most unfortunate thing about the early days of integration is how many of us were coached—by our parents and the mores of Southern culture—to move on and repress the memories of what happened to us,” he wrote in an email. “What this project does is bring those tightly imprinted, yet closed recollections out into the open so that those who experienced this past can make sense of it. Even more important, these stories can be used by students today so they can get a sense of how much the past had an impact on education today, yet also led to a positive transformation of the structure of Southern society.”

Rita Watts Boone, Crystal Springs Attendance Center class of 1970 (courtesy of The Admissions Project Digital Archive)

In “There Were Moments When I Could Hardly Breathe,” Rita Boone revisited the constant hostility she endured as one of ten Black students to integrate Crystal Springs Attendance Center in 1967 as a tenth grader.

“My memory is of my adolescent self just trying to exist, hour by hour, day by day,” she wrote. While the stately Gothic-style maroon brick high school was a better facility than her Black school had been, it was also “a world where no one played by the rules and good didn’t necessarily rise to the top.” She was kicked, spit on in the stairwell, and ostracized. Her history teacher theatrically mispronounced “Negro” as “Nigra.” Boone paid a psychic price in putting her Crystal Springs experience into words.

“Rekindling those memories still has ‘that’ effect on me,” she wrote in an email. “But it’s worth it for a good cause.”

Many white students in my own Greenwood eighth grade didn’t leave public school as I did. One of my favorite site essays is by my white, hometown peer Timothy Alford, who wrote “Mulgrew Miller Saw Us Through.” I only learned from reading his essay that when I moved to the corrugated steel academy in a U.S. 82 West cotton field for a “quality education,” I missed the opportunity to be in class with my African American peer, the late Mulgrew Miller, who would go on to become one of the world’s most celebrated jazz pianists. At newly integrated Greenwood High, the music program began to fuse Black and white together.

“Music heals,” Alford wrote. National online jazz forums circulated Alford’s Admissions Project account for its unique glimpse into Miller’s Delta beginnings.

As a corrective to the notion that public schools have been ruined, Skylar Smith, a rising Millsaps College junior, writes about her hindsight appreciation of her 2021 public alma mater. In “We Envied Private School Students. Why Weren’t We Taught Their History?,” she writes about how she and her peers bought into the notion that private schools were, by definition, a cut above their public schools. She even recalls riding by Jackson Preparatory School, founded as a segregation academy in 1970, and, from the road, wistfully projecting a Hogwarts glow on the campus, imagining ivy-covered walls and scenes from the Potter movies and Dead Poets Society. But seven miles east, where she attended the public Northwest Rankin High School, “our teachers talked about how to be anti-racist, not just not racist.”

IN THE PUBLIC SCHOOLS, A “MISSISSIPPI MIRACLE”

Von Gordon finds silent truth stuffed between the crevices of the public and academy accounts.

“We didn’t have to be separated,” Gordon says. Students “who went to segregated academies probably went having been socialized or told some things by people who loved them that were inaccurate.”

Who is telling the stories is crucial. Three generations after integration, many alums invest gauzy collective memories on their academy time, buoying academies forward for another generation.

“I’ve heard parents who went to segregation academies say, ‘I want my child to have the same wonderful school experience that I had.’ You know, Mayberry,” says Nancy Loome, a Clinton, Mississippi, stay-at-home mother of twins and public school advocate. “But that’s not the world we live in. We don’t live in a segregated world. We shouldn’t want to live in a segregated world, but I suppose some people do.” Loome is executive director of the Parents’ Campaign, a nonprofit that lobbies for public school support on the state level.

Von Gordon, head of the Jackson, Mississippi-based racial reconciliation nonprofit the Alluvial Collective

Meanwhile, in the parallel world, Mississippi public schools are posting exceptional increases in reading test scores. The New York Times, PBS, Associated Press and education publications all have covered “the Mississippi Miracle.” Times columnist Nicholas Kristof, for example, published “Mississippi Is Offering Lessons for America on Education.” His column noted how school systems nationwide are borrowing from the methods used in the last decade in Mississippi public elementaries: championing the science of reading through effective teaching, a phonics component, and repeated structured testing. Coaches work with teachers whose results lag the positive trends.

Different people have different explanations of Mississippi’s rising test scores. Republican politicians attribute the rise to a third-grade “reading gate” requiring passage of a reading skills test before promotion to fourth grade. The third-grade test requirement creates a clear objective, Loome agrees, but argues that without resources to remediate third graders who need more help before they can retest and pass, the Republican cutoff is punitive. Her group lobbied for the resources to provide remedial teaching. To her, the improved scores reflect the cumulative effects of a thirty-year gain in state school funding. Loome can show you a spreadsheet tracking the connection between state school funding and test scores since 1992.

“Every time we were able to get big chunks, additional resources, our scores went up,” she says. “It’s uncanny the correlation between these fourth-grade reading scores and funding for public schools. They track almost exactly.”

Despite the rising scores, I suspect academy supporters will keep talking euphemistically about how their schools offer a chance at “quality education.” That’s always been an integral part of their claim. Setting a foot inside a public school in their town? Not necessary.

Sometimes, I wonder—and white people, stay with me here because this is for you—if there’s a community out there now that’s interested in a voluntary do-over, a town willing in good faith to come together to do better in 2023 than its white residents would or could have done in 1970. How powerful would it be if a school system attempting this became a national model? I imagine major charitable foundations tripping over each other to be part of a transformative example. If you can make Mississippi work, you can make the U.S. work.

Mississippi is America writ large. Loome sees that in the school divide.

“There’s so much that’s divisive today,” she says. “But when children go to school together, they embrace the differences. They grow up with a natural part of their existence as friendly debate. Hanging out with people who don’t think the way you do about every single thing—but being good friends despite that. Children who don’t have that experience miss a lot. They don’t realize they’re missing it, because they’ve never had the experience. They miss a lot, and we as a society miss a lot. They’re going out into society as adults lacking that.”

I did. I lacked that. And now, I know so. Vaclav Havel, the dissident Czech writer turned eventual Czech president talked about the worth of facing up to past failures, however delayed.

“I would be delighted to hear things called by their proper names once more, delighted that being was revealed in all its fullness,” he said. “All was not lost.”

Coming to terms with past history is not nothing. It’s the only place to start, in fact.

In the meantime, more Admissions Project essays are coming. Among other pieces-in-progress, you’ll be reading in coming months about a Black academy high schooler realizing a dance was cancelled over worries she’d attend and an academy middle schooler who switched to a nearby all-Black school—and discovered the world didn’t end.

I rely on the 1962 words of James Baldwin, who recommended, writing in The New York Times Book Review: “Tell as much of the truth as one can bear and then a little more.” I think The Admissions Project writers are doing so. Baldwin closes that piece with famous words that I hope ground The Admissions Project: “Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced.”

I know we can keep facing the past. I know we can face it better. Send your stories.

Ellen Ann Fentress writes about Deep South politics and culture and is the author of The Steps We Take: A Memoir of Southern Reckoning. Her essays have appeared in The New York Times, The Atlantic, The Washington Post, Oxford American, Bitter Southerner, Scalawag and Dorothy Parker’s Ashes. Four years ago, she launched The Admissions Project, an online forum about racial equality in southern schools, including the impact of the legacy 1970s segregation academies, many now educating a third generation of students. Tax-deductible donations to the project can be made to the Eyes on Mississippi Fund at the Community Foundation for Mississippi: https://cffms.fcsuite.com/erp/donate/create/fund?funit_id=1287