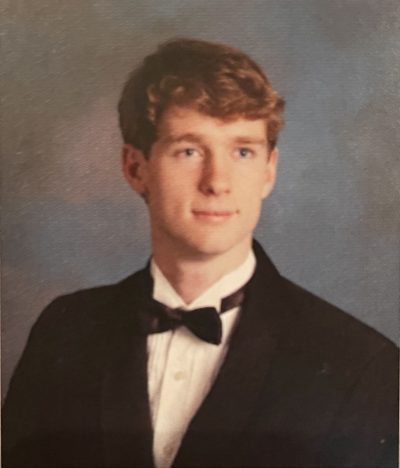

Caleb Bedford–Class of 2012–East Rankin Academy–Pelachatchie, Mississippi

In 2022, I learned something I should have figured out more than a decade earlier. I was listening to a podcast called Once Upon a Time at Bennington College, and an episode on Mississippi writer Donna Tartt brought to my attention a term that I had never heard before: Segregation Academy. It was a part of history that I had never been taught before, perhaps because I had attended East Rankin Academy, a school that fits the definition perfectly, with no room for argument.

A cursory glance at the East Rankin Academy website will tell you all you need to know about the school’s history. The truth is there, even if it’s glossed over by phrases lauding academic excellence and the all-important “Christian education” the school claims to put first and foremost. At the top of the website, you will find a Bible verse, Proverbs 22:6, which states: “Train up a child in the way he should go.” This speaks volumes, particularly when you look a little closer, and you start to see some more interesting information. Most interesting, perhaps, is the year of its founding – 1969 (classes began in 1970) – which happens to coincide with the rather late desegregation of schools in the state of Mississippi, a whopping sixteen years after Brown vs. Board of Education decided that segregating schools based on race was unconstitutional. Many parents of white children decided they would not stand for it, and founded hundreds of “segregation academies” or “seg academies” across the south, something that I did not really understand the extent of until much later, long after I left the pale halls of East Rankin Academy.

There was one instance, when I was in high school, that the subject came up. I do not remember all of the details, it being more than ten years ago, but for some reason my history teacher (the vice principal and daughter of the headmaster and founder of the school) was out for the period and the Headmaster filled in. (Yes, he was still called the Headmaster up through my graduation in 2012. The role and title have shifted now, according to the school’s website; the position is now called “head of school” and is filled by my old vice principal and history teacher. So, things have changed, but not really.)

Whatever the reason for her absence, the class took an unexpected turn. Perhaps we were talking about desegregation, perhaps the subject was simply on his mind; but the Headmaster began to talk about the founding of the school. He avoided certain words, specifics, and I do not remember everything he said, but I remember him admitting that they had been wrong to fight desegregation. Of course, he also made the typical excuses, saying that “that was how they were raised” and “it was a different time” and other such things that, although probably true, diluted any sincerity contained within the message. There was some beginning level of change, or remorse, or something in the man, but whatever it was never made its way into the school.

For one year, we had a single Black student in the upper school. She did not return, and I cannot blame her a hell of a lot. What must it have been like to be an outsider in that atmosphere? Not everyone I went to school with was racist, at least not openly, but some were. Maybe they did not say things to her face, but words were said at lunch tables that even made me uncomfortable at the time. Did I speak up against this prejudice, this open bigotry? I do not remember ever doing so. I suppose that makes me a coward, or worse, but there is not much honor in lying about it now.

Before attending East Rankin, I had attended a public school in the suburbs in North Carolina where I remember having only one Black classmate in several years, and a worldview-altering year at Brandon Elementary in the fifth grade, where a third or more of my classmates were Black. “Why the seeming fixation on race here?” you might ask. It is a fair question, and one that I do not have a great answer for other than the simple fact that race has been an issue in the South for hundreds of years. Having attended a seg academy, I was essentially able to avoid the issue for my entire middle and high school years, formative years in a young person’s life. I have since, primarily in the past five years or so, began to reckon with the issue myself. What, exactly, did this “Christian” education that the school espoused so vehemently, really mean? From what I remember, it had more to do with appearances than behavior.

The dress codes were strict. In addition to the uniforms, we were only allowed to wear shoes that were white, black, brown, or matched school colors. Our socks had to cover our ankles, and they had to be white. Belts must be worn at all times, shirts tucked in. On Wednesdays, we wore white. It was a church day, which apparently had something to do with it. Hair for the boys could not touch the eyebrows, ears or collar. No hair dye. In some sense, a dress code can be a good thing. It can put everyone on an equal playing field, theoretically eliminating a certain amount of bullying. However, the strictness of the dress code was such that individuality was effectively stripped from every student. There was no allowance for expression of personality. In a lot of ways, that sort of sums up the school for me. Everyone was being forced into this image of who the school thought they should be, rather than who they were meant to be. At the very least that is how it felt as a student. We were being trained up in the way they thought we should go, and it had a hell of a lot more to do with presenting well than learning to think or perform. Appearances were shown to be far more important than anything. The only time I got detention was for three separate instances of petty dress code violations. I wore the wrong socks, my shirt came untucked, and I forgot my belt. This was the same year I flunked Chemistry, but the real issue was my appearance.

It is interesting, to say the least, looking back from more than ten years down the road at my school experience. What stands out to me more than anything is not what I was taught, but what I was not. Perhaps that is a normal thing for people. Perhaps it is indicative of my experience in a tiny, essentially segregated if not officially, private school in central Mississippi. I have discovered many, glaring gaps in my education, some more egregious than others. We all have them, but when I look at what those gaps are, and the history of where I attended school, it is difficult to see the two as anything but some sort of intentional. We were not taught certain things because those things would make the school look bad. Maybe I cannot prove it, but the connections are there, if you have a mind to look.

Caleb Bedford is a writer and bookseller in Jackson, Mississippi. He is also a graduate of Mississippi College, where he escaped with a degree in English Literature. He has written two novels and countless short stories.